Unfortunately, modern Europe meaningfully denies its Christian inheritance. There is no mention of Christianity in the constitution of the European Union, due to a false concept of political correctness. In a number of German regions and Italian municipalities decisions are being made to forbid Christian symbolism in the schools. As a result of this false tolerance, Christianity is being pushed further and further to the fringe of social life, and antichristian views and morals are not only being legalized, they are being encouraged. The legalization of homosexuality, considered a criminal offense before World War II, has in certain places become a veritable «gay dictatorship.» The legalization of euthanasia in Holland alone has already led to hundreds of victims, many of whom departed this life against their own will. The legalization of abortions is leading to a real depopulation of Europe, and the demographic vacuum is being filled with migrants from third world countries.

As a result of liberal movements, the change in moral and judicial paradigms and the virulent battle for «human rights» that follow, we have arrived at quite a strange result: the actual, or existential, rights of man have precipitously narrowed in modern society. What were earlier considered man’s inalienable rights—the right to give birth, to raise children as upstanding and uncorrupted persons with a normal sexual orientation, the right to be chaste, to abstain from sexual life until adulthood, the right to publicly express one’s faith, rights over one’s organs, and the right to a natural death—are becoming more and more ephemeral in modern society, before our very eyes. In general, existential rights have suffered a much greater loss than have the rights to freedom. Thus, the existential right to work is sacrificed for the sake of free enterprise; it is becoming an object of merciless competition and unbounded tyranny on the part of employers. In the example of millions of homeless people in our country (and not only in our country) we see what seemed to be an inalienable existential right to a dwelling place obviously losing out to the right to freedom of movement. The modern social consciousness, as it is expressed in the mass media, is not disturbed when it sees a hungry, downtrodden homeless person; but it is up in arms when it hears that some sufficiently wealthy member of the intelligentsia is being prevented from leaving [Russia] for America (or somewhere else). The right to protect your health has clearly been overtaken by the right to do whatever you want with it. In our modern, post-industrial society, large amounts of money or substantial insurance are needed in order to get effective medical treatment. However, a person has every right to smoke, drink, take drugs, or sell his own organs. It is telling that one of the first decrees by the democrats when they came into power in Russia was to do away with forced treatment of drug addicts. The result is obvious: (according to various statistics) there are from one to two million drug addicts in Russia.

A similar situation arose as a result of the liberal movement of the 1960’s and 70’s, although their ideological foundation was formed back in the nineteenth century after the crisis in Europe’s consciousness and sense of justice. Here is what the great Russian philosopher, Ivan Ilyin,[1] writes remarkably about this:

«The understanding of justice has lost its ground; its motives and impulses have become one-dimensional. It has lost its noble direction, its original, sacred premises, and has submitted itself to the spirit of skepticism, in which everything is doubtful, to the spirit of relativism, and to the spirit of nihilism, which does not want to believe in anything. Our sense of justice has lost its ability to see [the difference between] good and evil, law and lawlessness; everything has become conditional and relative, and a bourgeois lack of principles and social indifference has settled in. An epoch of spiritual nihilism and public venality has taken over. In the nineteenth century, an abstract and formal jurisprudence flourished in Europe, which dealt only with positive law, and did not want to hear about natural law (that is, true, ideal, law of conscience); in it could be found only scant hints at social ideas, and the pale remains of Christian ideology, both of which where considered ‘subjective and unscientific.’»[2]

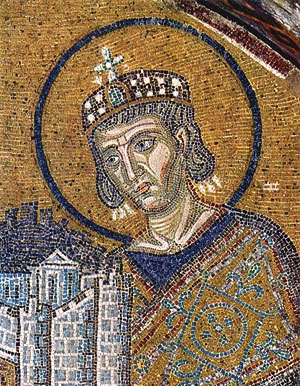

In order to arrive at an authentic and healthy juridical understanding of tolerance on the basis of «conscientious» and natural law, we will analyze one of its monuments—Emperor Constantine’s Edict of Milan (313).[4]

Actually, it was the creation of Constantine alone, accepted despite the objections of other caesars, first of all of Maximinus and Galerius. Constantine received his good disposition towards Christianity from his father, Constantine Chlorus, in whose realm Christians practically lived without being persecuted. However, Constantine converted to Christianity because of the miraculous sign of the Cross that he saw in the sky, and the voice which said, «With this sign, conquer» (Εν τούτω νίκα), before the battle with Maxentius.[5] The Edict of Milan, which was passed down to us in volume X of Eusebius of Ceasaria,[6] is truly the work of Constantine, and expresses his real views on religion and religious freedom. Noteworthy is the beginning of the Edict:

«Having long considered that the freedom to worship God should not be forbidden, but to the contrary, that the mind and will of every individual should be allowed to attend to divine things as he chooses, we have issued a command that all, even Christians, preserve their own faith and worship of God.»[7]

First of all, note the words, «Having long considered.» Constantine saw not only the good example provided by his father, but he also experienced the cruelty reigning in Diocletian’s court, when he saw with his own eyes how hundreds of Christians were burned, beheaded, and executed in other ways simply because they refused to bring sacrifices to the emperor as a god. Despite this bloody experience, or perhaps because of it, Constantine obtained a firm conviction that religious freedom was necessary. At first glance, it seems absolute here. But that is only a first impression. The key words here are, «the mind and will of every individual should be allowed to attend to divine things as he chooses.»[8] A similar meaning is applicable to thought, and thus, to the presence of a philosophical understanding of religious rites, a known theological system, a specific rational premise, and the socialization of religious rites. Constantine’s words do not at all allow for the legalization of destructive and antisocial cults, and it is no accident that one of Constantine’s first orders was to ban cults that practice human sacrifice.

At the foundation of religious freedom, the holy Emperor Constantine assumed «common[9] and right sense,» (υγιεινω και όρθοτάτω λογισμω έδογματίσαμεν), and these words are significant in the highest degree: they were governed not by political affairs, nor by blind tradition, but by philosophical logos, organically united with practical, common sense. It is no accident that Constantine the Great grew up in Britain, in Eboracum (later, York); centuries later, the inhabitants of Albion[10] would forge a great empire and great culture based on the holy Emperor Constantine’s spiritual inheritance, and thanks to that very «common sense.»

Thus, the apostolic emperor appealed first of all to the principles of natural rights, based upon natural «common and right sense.»

Nevertheless, this is not the only premise that motivated the holy Emperor Constantine. There were higher motives as well:

«Amongst all else that is beneficial, we decided to publish an edict, which would support the fear of God and reverence, in Christians and everyone, to freely choose their faith according to their own desire, that the Heavenly Divinity, as He is, might also be well disposed to us and to our citizens.»[11]

The following conclusions should be drawn from this very important passage.

1. The basis for the edict is not indifference, but to the contrary, religious feeling—the fear of God and reverence.[12]

2. Constantine’s thought proceeds from philosophical monotheism: «That the Heavenly Divinity, as He is, might also be well disposed to us and to our citizens.» The question arises: How are we to understand these words? Is it possible to infer that St. Constantine preached «indifference of religion?»

A careful analysis forces us to answer this question in the negative. Constantine’s subsequent actions and the text of the edict itself show that for him this Heavenly Divinity is the Christian God. From his qualification: «Everyone … freely choose their faith according to their own desire. Thus do we specify, so that we would not seem to diminish the dignity of any faith...» we see that there could have arisen from amongst Constantine’s audience the groundless suspicion that the Emperor himself was more inclined towards the Christians, and that this edict favors them over others.

Most likely Emperor Constantine was holding to the principle of «political correctness,» because politics is the art of the «possible.» He could have been striving to achieve equilibrium amongst his subjects, taking into consideration the fact that Christians comprised only ten percent of the empire’s population. However, another explanation is possible: Constantine uses a missionary method similar to the Apostle Paul’s, by beginning his preaching from the altar of «the unknown God.» He appeals to something common to pagans and Christians alike—the concept of One Heavenly God. Constantine as if steps out upon the same path of the Apostles, by preaching «the Most High God» to the pagans. On the other hand, he supports the line of apologists who appeal to the philosophical concept that pagans had of a Higher Heavenly God, the bringer of justice, the Father of the people. The subject of «fear of God and reverence» is very important as the basis of a consciousness of law, and of the Heavenly Divinity’s good will, as the necessary result of functioning law. Constantine the Great thereby creates the presupposition of the teaching on a supernatural origin of law itself, which is expressed with utmost clarity in the Eclogue—a monument of eighth century Byzantine legislation:

«The Lord and Creator of all things, Our God, Who created man and vouchsafed him self-rule, gave him law as an aide, according to the words of the prophets, which determined what should be done and what should be avoided, as well as what should be chosen as accomplishing salvation, or something which should be feared as bringing punishment. No one who keeps His commandments, or—and may it not be—no one who breaks them will be deceived with respect to one or another corresponding recompense. For God has determined both of these beforehand, and His commandments are in force immutably, rewarding each according as he deserves for his deeds; and, according to the Gospels, this is irrevocable.»[13]

Just the same, a known material base was brought in under this law; namely, complete restoration of all that was taken away from Christians during the time of persecution:

«Moreover, in the case of the Christians especially we esteemed it best to order that if it happens anyone heretofore has bought from our treasury from anyone whatsoever, those places where they were previously accustomed to assemble, concerning which a certain decree had been made and a letter sent to you officially, the same shall be restored to the Christians without payment or any claim of recompense and without any kind of fraud or deception, Those, moreover, who have obtained the same by gift, are likewise to return them at once to the Christians. Besides, both those who have purchased and those who have secured them by gift, are to appeal to the vicar if they seek any recompense from our bounty, that they may be cared for through our clemency. All this property ought to be delivered at once to the community of the Christians through your intercession, and without delay. And since these Christians are known to have possessed not only those places in which they were accustomed to assemble, but also other property, namely the churches, belonging to them as a corporation and not as individuals, all these things which we have included under the above law, you will order to be restored, without any hesitation or controversy at all, to these Christians, that is to say to the corporations and their conventicles: providing, of course, that the above arrangements be followed so that those who return the same without payment, as we have said, may hope for an indemnity from our bounty.»[14]

Emperor Constantine thus restored the principle of natural justice, not only returning to the Christians what was taken away from them during the time of persecution, but also remunerating the purchasers of Christian property from the treasury. Moreover he insists in the edict upon full and unconditional return of all property. Observe how far the Emperor stands above not only the unconscionable soviet authorities, who did not recognize any right by the Church to own property, and even obliged it to build apartments for the relocation of people who were living in the St. Sergius Lavra at onset of its restoration, but even above the democratic authorities, who still cannot bring into life the rather modest law passed by the President of the Russian Federation in 1993 regarding the restoration of Church property. The Church is still being given back only churches (most of which are in outrageously tumble-down condition), and rarely its former infrastructures (almshouses, buildings that belonged to brotherhoods and clergy, lands that belonged to the Church, etc.).

Meanwhile, in another order sent to the proconsul Anulin explaining the meaning of the Edict of Milan, St. Constantine unequivocally ordered that not only churches and houses of prayer be returned to Christians, but also all of their properties.

«Loving that which is good, we do not intend to claim property that does not belong to us, but rather we desire, most respected Anulin, that it be returned to its owner. Therefore, we wish that when you have received this charter, you will enact without delay the restoration to Christians of the catholic Church in every city or other place all that belonged to them but which is now in the possession of citizens or other persons; for we have decreed that churches be given back their former property. If you, a pious one, see clearly the meaning of this our command, then take care that the orchards, houses, and in general all that belonged to these churches be returned to them in their entirety without delay.»

This edict is quite instructive to us. The crisis of the modern Russian sense of justice, and the resultant social instability which threatens serious conflict in the future, comes from a lack of respect for others’ property, and the illegitimacy of modern governmental and personal property. The rapacious property-grabbing of the 1990’s, obviously requiring revision from the legal, moral, and governmental points of view, would never have been possible without Lenin’s slogan, «Steal what was stolen,» or without the experience of post-revolutionary expropriation and collectivization of the 1930’s. If we truly wish to restore the legal framework of Russian statehood, without which it can never stabilize or develop, then we must follow the example of Constantine the Great, and «loving what is good,» return property to the owner. This process should begin with the Church.

It is extremely significant that Constantine the Great recognized the Church’s status as a legal entity. One passage in the Edict of Milan is characteristic of this:

«And since these Christians are known to have possessed not only those places in which they were accustomed to assemble, but also other property, namely the churches, belonging to them as a corporation and not as individuals, all these things which we have included under the above law, you will order to be restored, without any hesitation or controversy at all, to these Christians, that is to say to the corporations and their conventicles: providing, of course, that the above arrangements be followed so that those who return the same without payment, as we have said, may hope for an indemnity from our bounty.»

Later, thanks to this order, the Church could accept gifts and inheritances, and, consequently it could conduct massive charitable work: support hospitals (όρφανοτρόφεια), old age homes, (γεροντοτρόφεια), feed the poor and the sick, help widows, and so on. It is notable that soviet legislation destroyed the Orthodox Church’s status as a legal entity and recognized as a legal entity not the parish, but the so-called «dvastatka»—a group of twenty laypeople—as the trustees of a parish.

Constantine’s activity following the Edict of Milan is a remarkable example—on the one hand, of healthy support for everything positive that Church life brought, and on the other hand, tolerance. He took a whole series of measures for the Church’s benefit: he gave the Church generous donations of money and lands, freed the clergy from social obligations «In order that they might serve God with all zeal, because this brings much benefit to societal affairs as well,» he declared Sunday a day of rest, banned the torturous and shameful execution by crucifixion, took measures against the discarding of newborns, and so on. On the other hand, even after his victory over Licinius and his final conversion to Christianity (around 323), he does not force any measures against paganism, and only calls upon pagans in his edicts to convert to Christianity:

«For the preservation of peace I have decreed that those also who remain in the deception of paganism should enjoy peace as do the right-believing. Let those also who depart from obedience to God, if they so desire, use their temples, which are dedicated to falsehood.»[15]

From the codex of Theodosius we can see that all the way up to Constantine’s death (337), pagans had their own temples and priests, and served in the government.[16]

In conclusion:

On one side, Emperor Constantine based his edict upon natural law, appealing to common sense. On the other side, natural law, in the final analysis, rises to a supernatural source.

He bases his tolerance upon philosophical monotheism, which likewise already possesses specific Christian characteristics.

The Edict of Milan is penetrated with ideas of respect for freedom of worship on the one hand, and respect for other people’s personal property on the other. Even by itself, the granting of the status of a legal entity to the Church is very significant.

Supporting the Church in every way financially and organizationally, Constantine the Great at the same time did not consider it necessary to forcefully convert pagans to Christianity, neither for the sake of peace in society, nor in the name of religious freedom. However, his tolerance was based not upon indifference, but upon philosophical monotheism on the one hand, and upon the evangelical principle of Let both grow together (Mt. 13:30) on the other. Without exaggeration, Emperor Constantine stands at the beginning of Christian civilization and Christian law, which includes the Christian concept of tolerance.

[1] Ivan Alexandrovich Ilyin, (1883–1954), Russian Christian philosopher, writer, and polemicist of the Slavophil school. A member of the nobility, he was a monarchist, and anti-communist. Ilyin was exiled from Russia in 1922, and died in Switzerland. —Trans.

[2] I. A. Ilyin, The Path to the Obvious, (Moscow, 1991), 248.

[3] See I. A. Ilyin, On the Essence of the Sense of Justice.

[4] A classic work on the history of the Edict of Milan was written by I. A. Brilliantov, Emperor Constantine the Great and the Edict of Milan of 313 (Petersburg, 1916); one of the more recent works in Russian with an exhaustive bibliography is by A. D. Rudokvas, «Characteristics of religious politics in the politics of the Roman Empire at the time of Constantine the Great,» http://www.centant.pu.ru/aristeas/monogr/rudokvas/rud010.htm.

[5] Many scholars allow that this really happened. See, for example, A. N. M. Jones, The Later Roman Empire (Oxford, 1964), 80.

[6] G. Bardy, Ed., Eusèbe de Césarée, Histoire ecclésiastique, (Sources chréttiennes 55. Paris: Cerf, 1958 [reprint 3:1967], X.5.4:100.

[7] This and subsequent translations of the Edict are from the Russian text (unless otherwise noted). Other English translations read somewhat differently. However, the author’s argument proceeds from the meaning shown in these citations. –Trans.

[8] Τη διανοία και τη βουλήσει έξουσίαν δοτέον του τα θεια πράγματα τημελειν κατα την αΰτου προαίρεσιν.

[9] The phrase that in English translates as «common sense» is in Russian, literally, «healthy understanding.» –Trans.

[10] The oldest known name of Britain. –Trans.

[11] Τινα εδόκει έν πολλοις ςπασιν έπωφελή είναι, μαλλον δε έν πρώτοις διατάξαι εδογματίσαμεν, οίς ή προς το θειον αίδώς τε και το σέβας ένείχετο, τουτ έστιν, όπως δωμεν και τοις Χριστιανοις και πασιν έλευθέραν αίρεσιν του άκολουθειν τη θρησκεία ή δ άν βουληθωσιν, όπως ό τί ποτέ έστιν θειότητος και ούρανίου πράγματος, ημιν και πασι τοις υπο την ημετέραν έξουσίαν διάγουσιν εύμενες είναι δυνηθη (Eusebius, Historia Ecclesiastica, X. 5.4).

[12] Litarally, «shame with respect to the Divinity and respect» — οίς ή προς το θειον αίδώς τε και το σέβας ένείχετο» (Ibid.).

[13] Cited from Textbook of the History of Governments and Laws of Foreign Countries (Moscow, 2004), 1:340. The objection could arise that the author of the Eclogue was the iconoclastic emperor, Leo the Isaurian. However, it was passed in 726, before the iconoclastic persecutions, and essentially expresses the Byzantine juridical practice of the seventh to the beginning of the eighth centuries; that is, it could be considered an expression of Orthodox legislative tradition. The Eclogue in many ways influenced ecclesiastical law, and the laws of the Slavic peoples.

[14] From: Lactantius, De Mort. Pers., ch. 48. opera, ed. 0. F. Fritzsche, II, p 288 sq. (Bibl Patr. Ecc. Lat. XI), translation of: University of Pennsylvania. Dept. of History: Translations and Reprints from the Original Sources of European history, (Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press [1897?-1907?]), Vol 4:, 1, pp. 28-30.

[15] The Life of Constantine, 2:48.

[16] F. I. Uspensky, History of the Byzantine Empire (Moscow, 1995) 1:64.