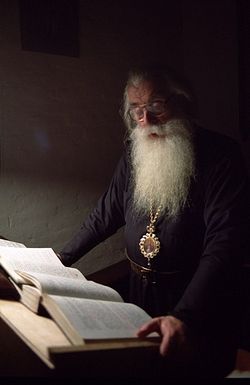

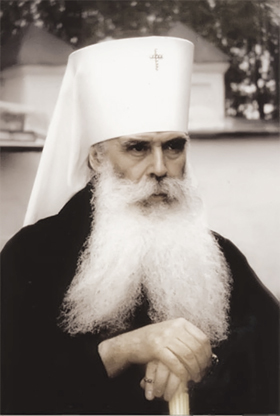

On November 4, 2003, the day the Russian Orthodox Church celebrates the Kazan icon of the Mother of God and the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus, a legendary figure departed toward the Russian horizon upon the sunset of an era. Metropolitan Pitirim of Volokolamsk, after a serious illness that lasted four months, reposed in the Lord. All of Russia knew this tall, austere prelate with a formidable beard and moustache, because he was inseparable from the ecclesiastical life of the capital; his name is likewise inseparable from the late twentieth century development of a publishing arm of the Moscow Patriarchate—no simple task in a time when schoolchildren were still being taught that "there is no God."

Perhaps a mystery to the outside world, Vladyka Pitirim nevertheless related many details of his life and thought to those close to him. His stories were so engaging that resourceful and diligent assistants continually wrote them down, and after his death, respectfully published them in a volume entitled, Departing Rus'. The Stories of Metropolitan Pitirim.[1]From its pages emerges a unique personality, a born clergyman, and a dedicated hierarch of the Church. The book also illustrates how a sincerely religious man had to maneuver in such complicated times. The result is a testimony to the enduring, timeless qualities of a strong hierarch in Christ's timeless Church, through times both bitter and sweet.

These are the stories we will use to draw our little sketch. Vladyka himself categorically refused to write his own memoirs. "I won't write them. But I might speak…" he said, tacitly blessing those interested to record what he says. Then he added with a chuckle, "Only, if I see what you've written, I'll probably tear it up anyway." He was always hypercritical of his own works, and as his assistants wrote, "We had to save them from him."

Early life.

Metropolitan Pitirim was born Konstantine Vladimirovich Nechayev on January 8, 1926, in the town of Kozlov, later renamed Michurinsk, in Tambov Province. His father was a priest, as was his grandfather, and so on back to the seventeenth century. His father, Archpriest Vladimir Nechayev, would later be imprisoned for his faith.

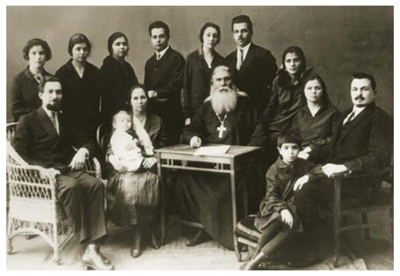

The Nechayev family. Konstantine is the baby on Olga Vasilievna's knees.

The Nechayev family. Konstantine is the baby on Olga Vasilievna's knees.

Vladyka's ancestors were part of a group of missionary priests brought to the region by St. Pitirim of Tambov to enlighten the native Mordorvian peoples. His ancestors even included a bishop.

"Bishop Nicholai (Dobrokhotov) belonged in part to my family. He had a dramatic experience in life, after which he became a monk. He was getting ready to wed… On the very day of the wedding a catastrophe occurred: his bride was murdered on the steps of the church. Instead of going to a wedding crown, the bridegroom walked, just as he was in his tailcoat and dickey, to the Kiev-Caves Lavra." Bishop Nicholai was later sent to St. Petersburg, and made bishop of Tambov.

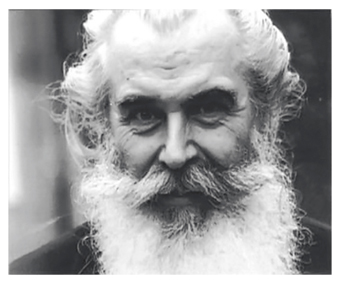

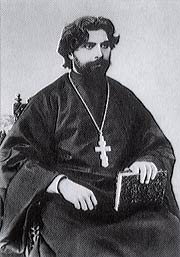

Fr. Vladimir Nechayev

Fr. Vladimir Nechayev

"In the freshman class were students who had just finished high school, and those who had already fought in the war, with contusions and wounds. There were those who had gone to the front after two or three years in the institute, and returned after being wounded. Among them was an invalid girl. She had only one whole leg—the other was amputated at the knee (she wore prosthesis), and both arms were gone up to the elbows… They treated her chivalrously; young students and adults alike took care of her. The fellows waited to open the door for her, to take her purse, remove her coat, replace the purse to her shoulder, then accompany her up the staircase while she slowly, heavily—no matter from what floor—moved her prosthesis up the stairs… She graduated with honors."

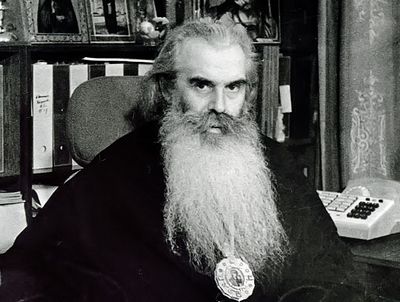

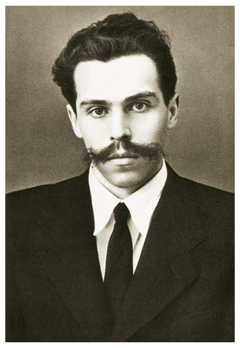

Konstantine Nechayev.

Konstantine Nechayev.

He begins to serve in the Church.

In 1945, Konstantine Nechayev began his service to the Church as a subdeacon in the Patriarchal cathedral. This beginning was connected in his memory with historical events both societal and personal.

"After the meeting of three metropolitans with Stalin,[2] everyone felt that some new period had begun in the relationship between the Church and the state. It was an unprecedented feeling. There were two such periods in my lifetime: one was then, and the other came after the celebration of 1,000 years since the baptism of Russia, when children started appearing in the churches. Nothing was officially announced, but all were living in expectation of changes. Then Patriarch Sergei died. I remember I had gone to the institute with my papers, and the secretary of the Komsomol committee suddenly said inexplicably, 'They've reported that some sort of Patriarch has died.'[3] I nearly dropped what I had in my hands. When I left the classroom, I went straightway to the Cathedral. They served a pannikhida. After the service, Kolchitsky[4] asked all the men—and there weren't many—to remain. The talk was about helping keep order during the funeral. I remember they placed me at the left door that opened into the court…This was my 'debut.' After that, they noticed me, and I would come regularly to help. […]

"On the fourth [of February] our Patriarch [Alexey (Simansky)] served, and then he noticed me… They invited me to come back. By the way, there was a certain "pause" when my family heard the date of the beginning of my service as a subdeacon: it was the night of February 3–4, 1930 when my father was arrested."

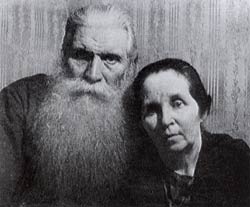

The last photo of his father and mother, Olga Vasilievna

The last photo of his father and mother, Olga Vasilievna

In 1951, Konstantine graduated from the Moscow Theological Academy, and in 1952 he was ordained a deacon. In 1954 he was ordained into the priesthood, and tonsured a monk in 1959, with the name Pitirim. In the same year, he was raised to the rank of archimandrite, and appointed dean of the Moscow theological schools. In 1963, on the feast of the Ascension, Archimandrite Pitirim was consecrated bishop of Volokolamsk, a vicariate of the Moscow diocese.

With Patriarch Alexy (Simansky).

With Patriarch Alexy (Simansky).

In 1962, Vladyka Pitirim began the work for which he is most remembered, as director of the Moscow Patriarchate publishing department. To understand what a difficult task this was under the extremely anti-religious regime of Nikita Kruschev, try to picture an enormous crowd in a desert, stumbling with fatigue, lips parched from thirst. A man appears on the horizon with tiny crew of water bearers. The rulers of the desert have banned the dissemination of water, but with the eyes of the world upon them, they can't let the people die. However, they have no intention of actually quenching anyone's thirst. The Orthodox believers in Russia were thirsting for the word of God, but books were very difficult to obtain.

The department was first organized after Stalin's meeting with three metropolitans in the fall of 1943. The first issue of the Journal of the Moscow Patriarchate came out in September. After that came a small presentation book entitled, The Truth about Religion in Russia, and then Patriarch Sergei and His Spiritual Inheritance. Vladyka Pitirim talks about his work on the JMP, and his managerial style:

"What does a new editor-in-chief do when he begins his job? First, he changes the editorial staff, and then he changes the cover, so that the new content would be seen through the 'jacket.' I invited artists to give me sketches for a new cover. It's hard to talk with artists in general. They draw any thing in the world that looks unrecognizable, and say, 'That's how I see it!' As I recall, I had 253 sketches, and had to explain to each artist, 'Please understand, this is my order, what I need!' In the final analysis, I chose three of these 253 sketches…"

The first assignment given him as editor-in-chief by the Patriarch was to write a critical article on one of Fr. Alexander Men's assertions. Fr. Alexander was, and still is, a controversial figure in the Russian Church. Vladyka approached the assignment with equal discernment:

"I always related rather cautiously towards [Fr. Alexander] Men. With all of his erudition, in his works he relied mainly upon Western sources. Well, there is nothing "harmful" in his books. What bothered me was something else. How did Men's books get published in mass quantities in the West and become available to us at a time when you couldn't even get a Bible through the border control? Furthermore, he had a particular idea—to create a Jewish national Church. In principle, there is nothing wrong with this. If there is a national Greek or Slavic Church, then why shouldn't there be a Jewish one? These ideas developed and spread at one time in Paris; they were fervently supported in part by Mother Maria (Skobsteva). But Fr. Alexander had put a particular twist on it. Just the same, one can't judge such thing categorically; it's all built upon halftones."

A lifelong dream.

Vladyka elaborates on the dearth of Bibles in his time:

"It was my childhood dream to publish the Bible. It is hard for the young generation to imagine how we longed for it. Over the course of several decades, the Bible was one of the most forbidden books, like the works of dissidents and indecent pornography. Some people even bought the Bible for Unbelievers by Emelian Yaroslavsky,[5] cut out the actual biblical citations with scissors, and pasted them into notebooks. They would get a thick, puffy book—but sacred text, after all."

The department began its work of providing service books for use in the churches.

"Then, during a very complicated period, we provided for the printing of the full body of divine service books. If you put them all together back-to-back, the shelf would be two meters long. We fulfilled this task, and all the churches were supplied with divine service books."

"When we began publishing the service books, we were printing them from the old editions, and not from what the Synodal commission of Metropolitan Sergiy [(Starogorodsky), later Patriarch Sergiy] had published. This was connected with the fact that Church practice had refuted those changes. I myself, for example, cannot read Sergiy's edition of the canon of repentance—the melodiousness is disrupted in it…

Vladyka goes on to describe the great significance of the department's work. His words are not self-adulation, but matter-of-fact, for time has proven them true.

"But my most important work, as people tell me, is this: I acquainted society with the Church. Through the word, through our periodical, through the press. The Journal of the Moscow Patriarchate was highly rated by experts.

"Censorship was extremely tough, but we made use of every opportunity. If we were forbidden to write that, 'after the service there was a cross procession around the church,' then we wrote, 'The service ended with a procession including the sprinkling of the faithful with holy water.' We could not even print the names of St. Seraphim of Sarov or St. John of Kronstadt; nevertheless, we mentioned them without naming them, using Aesopian language. Everyone knew what we meant—only the literary censor didn't understand it…

"Limits were very strict. For example, the maximum allowed print run for the Bible was 10,000 copies, although according to our rough statistics the number of believers who needed the Bible was no less than sixty million people." One of the only prayers for which the department was granted a maximum limit of 1.5 million was the prayer for the dead that is placed on the forehead of the reposed at burial. "Most other print runs were small, but one and a half million is something… So here is what we did: we printed a prayer for the living on the reverse side! They were all sold immediately…"

Outsmarting the authorities.

Vladyka's inventiveness extended to his direct dealings with the anti-religious authorities, who had the power to close down the publishing department, should they so decide. Calculated game-playing would not have been sufficient, however. One had to have a heart, and basic faith in human nature.

"I, of course, am not a typical 'product of the soviet epoch,' but I did have to go through the whole soviet school of Marxism and political economy, and therefore I was able to play on it. For example, Kuroyedov[6] had a chief assistant, with whom we had particular problems. One day I had a conversation with him as the director of an ecclesiastical publishing house. The discussion turned to the subject of Patriarch Tikhon and his relationship to the Soviet authorities, and then that assistant threw me a wonderful 'ball.' He said, 'Well, we do not doubt that you are loyal to the Soviet authorities.' I paused, and said, 'You know, you have insulted me! I won't forgive you for that!' He was a man from the central apparatus, 'sensitive,' and starting worrying. 'How? How did I insult you? ' 'You called me loyal, but I am normal,' I said, then added, 'Furthermore, you were born under the Tsar, but I was born under the Soviet regime.' I had no problem with him from then on.

"Atheism, in my view, is not so much an error as it is incorrectly chosen premises. Somewhere along the line conjecture, inertia, or narrowness of views came into play—in other words, a collection of secondary factors. I have associated with [communist] party figures under trusting circumstances, and I often saw in them simply good Russian people. 'I would like to believe,' they would say, 'but they never taught me…'

"I would be in an airplane… and my neighbor would say to me, 'Batiushka! I am baptized, Orthodox…' He would tell me how they celebrate the Church feasts at home, but that he doesn't go to church—it's forbidden. On the one hand, he has two worldviews—one is for people around him, and the other is for himself. That of course deforms the personality; but there is an inner voice after all, which turns a Russian back to his roots."

Vladyka also stood in the complicated position of intermediary between the "outside world" and the soviet reality of a Church under pressure.

"One day, at a meeting of party workers I even said, 'The most harmful anti-soviet organization we have is Intourist.'[7] The director of Intourist jerked, looked at me with surprised, rancorous eyes, while I continued, 'Judge for yourself what instructions you give to your guides. We try to prove to everyone in the West that there is no persecution against the Church here, but your tour guides tell visitors that we have no religion at all. And when the tour groups walk into an active church, the tour guide says, "No, no. I am forbidden to enter," and remains outside.' The party workers had to think about this, and soon those ridiculous instructions were removed."

The Baptism of Russia

In 1998, the memorable 1,000-year anniversary of the Baptism of Russia arrived. This was a major publicity time for the Moscow Patriarchate publishing department, and Metropolitan Pitirim applied all effort with an almost mystical dedication.

"The preparation for the 1,000-year anniversary of the Baptism of Russia was for us a time to sum up the Russian Church's historical path. We considered very important the theme of the Church's lower echelons' service of Church and Fatherland: priests, deacons, and acolytes, and their 1,000 years of tireless labor, the aggregate of that immeasurable spiritual experience by which we live today. We know very little about the lives of the white [married] clergy—those who bear the weight of the whole world on themselves. Most historical research is carried out along the more noticeable higher clerical ranks. Russian writers also found the simple village priest uninteresting—our classical literature often portrays only caricatures. Our duty was to gather this spiritual experience by bits. We began that work in those days."

Met. Pitirim notes on this subject, "Today we are canonizing many priests [new martyrs]. But for what are we canonizing them? Their parish and family life is remembered the least; we mostly remember that they were shot—either in 1917 or in 1937, or in the forties. Meanwhile, a priest's true podvig is his parish and family life."

Volokolamsk.

The monastery of St. Joseph of Volokolamsk.

The monastery of St. Joseph of Volokolamsk.

This unforgettable ecclesiastical figure touched the lives of countless people during his tenure in the publishing department and afterwards: government officials, army generals, chairpersons of humanitarian foundations both in Russia and abroad, filmmakers, writers, artists, and various other members of the Russian cultural elite. He concelebrated with bishops and even patriarchs from all around the Orthodox world, and was highly respected by leaders of other confessions. His exacting supervision influenced the lives of everyone who worked in his spheres, from the clergy in his diocese, to his editorial assistants, down to the drivers and cooks at the publishing office.

Thought.

Vladyka Pitirim's deepest side was, of course, deeply hidden. Vladyka himself noted that one of the strongest characteristics of old Russia was her people's self-restraint and reserve. He was taught, as was all his generation, to keep what was most precious within, like the Gospel pearl. This rare and beautiful pearl grew from generation to generation, within the seemingly imperfect outer shell of the Russian land. His thoughts on "spiritual concentration" offer a glimpse of it. Here are portions of this chapter.

"Some words are used in our day so frequently that their original meaning is completely lost. One of such words, or concepts, is spirituality. It is often used in a distorted way...

"Spirituality in the Orthodox understanding is that lofty level of personal inner development which, accepting everything, considers of highest value the eternal life of the soul in full concord with God's will. The soul cannot be measured by any values. When we come to God's Judgment, we will not be asked, 'Did you do anything to save the Karakumi desert or the Aral Sea, or to irrigate Afganistan?' God will ask—and we must answer—the question: 'What did you do with your conscience? Did you ever listen to it? How many times did you listen to it, and how many times did you neglect it?'

"Man was created by God immortal; he had limitless freedom of activity, but he was given a law by which he was obliged to live. This law did not chain him down, but gave his life direction. 'All things are allowed to me, but not all edifies,' said the Apostle Paul. Accepting everything, man chooses what is best. There is an old saying: 'Morality that needs to be protected does not deserve protection.' A man under house arrest or in solitary confinement will not commit any crimes, but that does not mean that he has become morally upright. A spiritual person may like classical music, but not all street music. He will read not only Pushkin, but even Mayakovsky; however, he is not likely to have Demyan Bedny[8] on his bookshelf. One must not only read the Bible; you have to read secular books as well. Russian culture, without a doubt, is spiritual in its main component. Our society is still more spiritual than what I have seen in most other countries, although this spirituality is now being thoroughly rooted out.

"It is also a distortion to equate spirituality with religiosity. I would say that an equal sign could be placed between 'spirituality' and 'humanness.' One of the ancient names of God is 'Strength'. The Greeks even have an exclamation before the Eucharist, when the bread and wine are already on the holy table—'Dynamis!' or 'Strength!' Man is the conduit of this divine strength in the world. As a rock is hard and fire is hot, so man is a spiritual being, and human substance itself is spiritual. A human soul can contain the whole world. But if a man has no spirit in him, he is not a man. Spiritual essence manifests itself in man in different ways. Anger and hatred are also manifestations of spirituality, and they are not always bad. 'I am burning with zeal for God,' is written in the scriptures."

* * *

In December, 1994, Metropolitan Pitirim was removed from his position at the publishing department by Synodal decision. Most of the dedicated people gathered at his ever-memorable department are still laboring for the Church—some have gone on to the Moscow Patriarchate Department of External Church Relations, others work for the Russian cultural foundation (which Vladyka Pitirim helped establish), others work for various Orthodox publishing houses. One very active publishing house was established at Sretensky Monastery by its father Superior, Archimandrite Tikhon (Shevkunov), who worked under Metropolitan Pitirim as a novice, having the obedience of filmmaker. All of these people remember that amazing time, when after years of harsh heat, the treasures of Orthodox literature were being drawn from the well of Russia's millennium of Orthodox Christian experience, and carried to a God-thirsting nation. And perhaps the greatest image in that mission still remains: Metropolitan Pitirim of Volokolamsk and Yuriev.