From Dostoevsky's Crime and Punishment.

From Dostoevsky's Crime and Punishment.

This seemingly random existential plea is a lovely example of our grasping, spiritual feelings toward Russian writers. At the moment of our deepest pathos, some of us think of them as the guides to transformational suffering. There is a type of Western romantic who holds fast to this belief: If we read more Chekhov, Tolstoy or Turgeyev, we might be different, even better people.

But what about Russia’s living literature? In her insightful introduction to “Rasskazy (Stories): New Fiction from a New Russia,” Francine Prose tells us that if we don’t know what Russians are writing today, it is not completely our fault. Only a few hundred books are translated into English each year from every other language, and that includes technical books.

But here we have it: A beautifully translated anthology that offers up some of the best Russian writers today—most of whom have not been published in English before.

“Bregovich’s Sixth Journey,” a short story written by Oleg Zeborn, warms the reader with a lyrical sensibility and a strictly Russian kind of light but incessant brooding. The main character studies contemporary Russian literature and finds it confounding himself. “I find it hard to study the stuff because it’s so close to me,” the character remarks to the reader….at the end of the twentieth century, it’s hard to tell: Is this a genuinely canonical writer or is it a pathetic ass____ who last week took a swing at his young wife and broke her nose?”

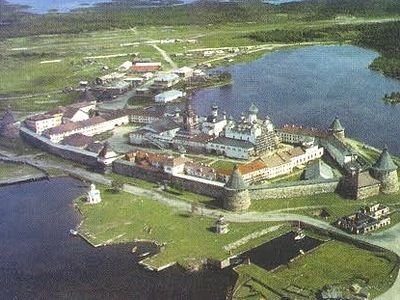

Once the protagonist, a teacher and writer, settles into his dacha to work, he is preoccupied by a neighborhood dog in chains. He feeds the dog pelmeni, plays Bregovich (I imagine it is the gypsy brass of Goran Bregovic) for him and names the dog Ivan Denisovich, from Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s famous novel (“One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich”). After staying up all night to work, the character ruminates on Solzhenitsyn, prisons real and metaphysical, and dogs. “I feel sorry for him, and for all the prisoners of our homeland, and even feel a little sorry for myself…I get out of the car and let Ivan Denisovich off his chain.”

Maria Kamenetskaya’s “Between Summer and Fall” is a piercing, funny and ultimately loving ode to the functionally dysfunctional family as it ages. Older parents meet with grown children at the dacha (one daughter in law can’t attend because she has gotten her lips augmented). They plant apple trees awkwardly, but in a spirit of détente.

Arkady Babchenko is the new Russian master of the memoir. His work is both confessional in tone and bereft of self-pity. Somehow he makes the Russian Army’s disciplinary battalion—a dank, festering, abusive and debased atmosphere, as hopeless as any of the gulags—approachable and eminently readable. His unembellished style and ironic humor draws the reader in, as if standing close to him, a specter over his shoulder who knows somehow he got out because he is writing this story and not rotting outside Grozny. Anyone following Russia’s current army reforms must read Arkady Babchenko’s story “The Diesel Stop.”

Already known for his journalism and first book “One Soldier’s War,” it is not lost on readers that he uses the same adroit translator here, Nick Allen. Babchenko recovered from his lifeless humiliation and addiction to war through writing about it. He has said in interviews that the process of writing transformed him into a new person.

Ah, there it is again, the transformation of character. Most of us cannot become Russian writers in hopes of changing our lives. But could reading more Russian writers help us reach that place called an examined life?

Start with Rasskazy, or Stories.

As editors Mikhail Iossel and Jeff Parker point out, Russia’s greatest contribution to the world over time is not oil or gas or arms. “Rather it’s been the successive generations of Russian writers capable of examining life’s emotional and intellectual restlessness, its complexity and intensity.

Here’s to the interior life.