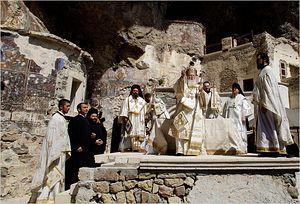

Ibrahim Usta/Associated Press

Alashehir, Turkey, May 4, 2011

|

| Patriarch Bartholomew I, center, the spiritual leader of the world's Orthodox Christians, conducted a service at the Sumela Monastery in Trabzon, northeastern Turkey, in 2010. |

Patriarch Bartholomew I, center, the spiritual leader of the world's Orthodox Christians, conducted a service at the Sumela Monastery in Trabzon, northeastern Turkey, in 2010.

“It makes you see the Bible in 3-D and color,” the guide, Dan Fennell, said of his tour of historical Christian sites around western Turkey.

Mr. Fennell, who is based in Jakarta, has been leading pilgrimages to Anatolia for close to a decade. But these visits have become richer and more rewarding, he said, because Turkey has been cultivating the historical sites of Christianity.

“In Laodicea, for example, where we are headed next, you can now see things you could not see five years ago,” Mr. Fennell said of the ruins of the seventh city addressed by the Apostle John.

A Muslim nation long ill at ease with its pre-Ottoman history, Turkey has discovered Anatolia’s Christian heritage as a way of drawing visitors and of cultivating an image as a meeting-point and arbiter of civilizations.

“We have recognized this as a special field of tourism and as a special cultural wealth,” the Turkish culture minister, Ertugrul Gunay, said in an interview in Ankara. By next year, his ministry aims to increase the number of religious tourists to Turkey to more than three million, from 1.3 million last year.

“Until now, our concept of faith tourism was limited” to Muslim shrines “like the Mevlana tomb in Konya or the Halil-Ur Rahman mosque in Urfa,” Mr. Gunay said, “even though Anatolia is the home of important shrines of Christianity and Judaism as well.”

“Now,” he added, “we are working to care for all of these sites, Muslim, Christian and Jewish, without discrimination, to restore them and maintain them and to open them up to the public to visit.”

A case in point is the ancient metropolis of Laodicea, in southwestern Turkey, where Turkish archaeologists unearthed a spectacular church dating to the early fourth century.

“This is one of the oldest churches in the world to survive in its original state,” said Celal Simsek, the archaeologist who is leading the excavation team that has worked through the winter to reveal the huge church that was first spotted underground last year on a radar scan. “When the 10 most important archaeological discoveries of the 21st century are totted up one day, this church will definitely be on the list.”

Mr. Simsek dates the construction of the church to between 313 and 320 A.D., immediately after the Edict of Milan, by which Emperor Constantine I of Rome legalized Christianity in the year 313.

Scrambling around the church, which has 10 towering pillars on a floor area of 2,000 square meters, or 21,500 square feet, flawlessly preserved mosaic floors and a walk-in baptismal fountain for mass christenings, Mr. Simsek said he was hoping to invite the pope to the official unveiling of the restored church, tentatively planned for next year.

“I expect an onslaught of visitors in the coming years,” Mr. Simsek said.

Pilgrims have already begun pouring in, on the last leg of a tour through the sites of the seven biblical churches, all of which are in western Turkey. Tourism to the site increased tenfold in the first months of this year, to 1,000 visitors a day, Mr. Simsek said, adding that “90 percent of visitors are pilgrims.”

Mindful of the revenue that tourists provide, the nearby town of Denizli, in a first for Turkey, is now supporting the Laodicea digs financially, adding a million dollars year to financing from the local university and the Culture Ministry.

It is a vein of tourism that other towns in heritage-rich Anatolia have begun to invest in as well. The small northwestern town of Iznik, which has long marketed itself on the fine tiles produced there in Ottoman times, now evokes its former incarnation as Nicaea, site of two of the seven Ecumenical Councils that shaped the basic tenets of the Christian faith.

All seven councils were held on what is now Turkish soil — the two in Nicaea, three in Constantinople, now Istanbul, one in Ephesus in western Turkey and one in Chalcedon, the modern-day Kadikoy district of Istanbul on the Asian shore of the Bosphorus. Last year, Iznik invited historians from the Vatican to join a search for the exact location of the first Council of Nicaea, at which bishops from all over the Roman Empire gathered in 325 to draft the creed that is recited by Christians around the world to this day.

The Nicaean church in which the seventh Council dispatched iconoclasm in the year 787 has been roofed and restored, and plans to build new hotels in the town are under way.

The local authorities are also working on a project to pair Iznik with the Spanish city of Córdoba, historical seat of the Islamic caliphate that ruled Iberia and northern Africa in the 10th century, in a “bridge of civilizations” that is to emphasize the shared historical heritages of Christians and Muslims and to promote intercultural exchange.

The partnership is to be sponsored by the Alliance of Civilizations, a United Nations initiative that is co-sponsored by the Turkish prime minister, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, and his Spanish counterpart, José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, and aims to fight extremism by fostering understanding and cooperation across cultures and religions.

“As the venue of two Ecumenical Councils, Iznik really has the potential to draw a lot of interest from all over the world,” said Mr. Gunay, the culture minister. “So we are trying to promote Iznik and to restore it.”

He said the government had also granted permission for annual religious services to be held in several historical churches that are otherwise classified as museums, which makes it illegal to worship there. One is the Church of Saint Nicholas in Demre, ancient Myra, which is visited by 400,000 tourists a year.

Another is the Orthodox monastery of Sumela, which is near Trabzon on the Black Sea, had been closed since 1923 and was re-opened last summer for its first religious service in 88 years, drawing thousands of Orthodox pilgrims.

Mr. Gunay vowed that more buildings would be opened to pilgrims, and local Christians, for worship. Islam, Christianity and Judaism had all left their imprints on Anatolia, he said. “We want people to know this. We want them to come and see it and to pray here.”