|

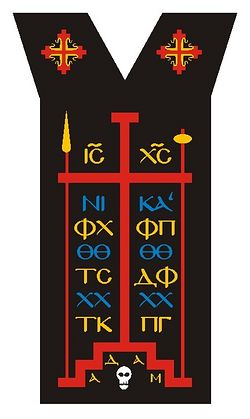

| The monastic schema |

At the end of the track, there is a long, neat building and a garden full of spring flowers and industriously cultivated rows of vegetables. On the moor beyond, newborn lambs stagger about. Inside, all is white and wood and ordered calm. The air smells of incense and creosote. Small, delicate vases of flowers from the garden decorate the window sills.

This is a Greek Orthodox monastery - apparently the only one in the country to adhere to a strict Orthodox tradition.

It is home to just two nuns: Mother Thekla, the Abbess, and Mother Hilda. They have agreed to talk to the Guardian - which means a visitor - because they would like to attract new nuns to their community of two. In a letter to me, arranging the visit, Mother Hilda wrote: "All we can do is let people know that we exist and something of our way of life."

It was 27 years ago that Mother Thekla and another nun, Mother Maria, moved here from a monastery they had founded in Buckinghamshire some 13 years before. In Buckinghamshire, they were prey to casual, curious visitors: here there is none of that. Today Mother Maria lies buried in the monastery's cemetery, along with another nun, Mother Katherine. Since then women have come to join, but Mother Hilda was the only one to stay.

And so there is just the two of them in residence. When I meet them, both are dressed in black, close-fitting veils and long, loose black robes. They say they wear black as a symbol of their own deaths to the world: "Our work is the work of corpses in the face of the world."

Dead to the world or not, these nuns practically explode with exuberance. Mother Thekla is 83, with sharp brown eyes. Every so often she giggles. Mother Hilda is perhaps 30 years younger, although she politely declines to reveal her age, explaining that she cannot discuss details of her pre-monastic life. She does reveal, however, that she joined Mother Thekla nine years ago.

As we talk, some details do emerge about the women's lives. Mother Thekla was born in Russia during the revolution. She had to be baptised in a vase, she says, because there was too much shooting going on in the streets for her parents to get to church. Soon afterwards they moved to England and she grew up in Richmond.

"I climbed every tree in Richmond Park and could recognise them all," she says. She did an English degree at Cambridge and worked for British intelligence during the war, partly in India, although she will not elaborate. She later became an English teacher.

Mother Hilda is a specialist in Byzantine studies, but is reticent about her academic background. She is from Philadelphia, and the odd Americanism pops into her speech as she talks - once she refers to cleaning up "dust bunnies". "She has a PhD, she's quite erudite," confides Mother Thekla.

"Oh Mother, come on - I'm an amateur," says Mother Hilda.

Neither nun leaves the monastery unless it is strictly necessary - an appointment with the doctor, for example. Their daily life at the monastery - the official name for it is Hesychasterion (prayerhouse) of the Koimisis (Assumption) - follows a regular cycle. Prayers they refer to as "offices" begin at 6am and are repeated at regular intervals until "midnight office". In all there are six prayer sessions each day: eight hours in all. Some of the prayers date back to the fourth century and are said in a beautiful church with icons on the walls. On Sundays and feast days an all-night vigil is added to the eight hours of prayer completed on ordinary days.

"This used to be the cowshed," says Mother Thekla, as we enter the church. "It's why we bought this place. We saw it and knew this would be our church."

In between prayers, the nuns are engaged separately in creative and practical work, coming together for simple meals in the refectory. "Spreading manure on the vegetables is one of my tasks for today," says Mother Hilda.

The monastery differs from a traditional convent in that the nuns live in what they describe as self-contained hermitages, or hermit cells, where they work and sleep, meeting only for food and prayer.

It is not a life of abject poverty. "We have the things we need but not the things we don't need," says Mother Hilda. There are no curtains or easy chairs but the furnishings are simple rather than spartan, as is the delicious lunch of rice, beans and salad which Mother Hilda prepares for us.

There is a microwave, a washing machine and a computer, but no fripperies. They grow much of their own food and freeze their produce to see them through the winter. Shopping for essential supplies is done a handful of times a year by Mother Hilda. Mother Thekla bakes bread and eggs are supplied by the local farm. They do not eat meat and dairy products are forbidden during Lent. "It is the monotony of our lives which frees the spirit; all the imminent things drop away," says Mother Thekla. "It's quite painful being faced with your real self without the trimmings. There's time here to pray for the world. That's our work: it's not something we do on our Sunday off."

Nationally, the number of women signing up for a life of poverty, chastity and obedience is falling by 8% a year. Mother Hilda believes there are a number of reasons. "Some blame the 'vocation problem' on luxury and self-indulgence but we will never manage to be as decadent as Rome or Byzantium," she says.

She believes that one of the reasons fewer women choose to enrol is a growing inability to sustain an "inner life". "We have been robbed of our inner resources; elevator music is all around," she says. "All the silences are covered. These days it is considered cruel to have a quiet classroom for children."

Is there too much instant gratification? She nods vigorously. She says that the women who came to the monastery but did not stay, did not "know what to do sitting in a room by themselves".

For Mother Thekla the decision to become a nun was sudden. "I went on a retreat and met mother Maria and that was it. I was called to it. It's a bit like a thunderbolt. You can't deny it when it hits you. I used to love things like visiting secondhand book shops but you can't compare life now with life before. It's like walking through a mirror backwards."

At one time choosing a life as a nun was an obvious career option. Poverty propelled many women into convents and although the lifestyle involved various degrees of separation from the world, nuns were a much more visible presence in mainstream society than they are today. "In the past strong, independent women with views of their own were attracted to this life but now because there are so many more opportunities for women to lead independent lives, fewer from this group are choosing to be nuns," says Mother Hilda. She says that people still want spirituality. "But they are looking for a magic key to unlock this spirituality and shift the responsibility for finding that on to someone else."

So why should anyone consider joining their monastery? "For a woman who is self-reliant and independent there is space here for her spiritual growth," says Mother Hilda.

"We have the knowledge that nothing worldly matters," says Mother Thekla. "We don't need success and achievement in the worldly sense. The soul is free and there's no competition and no jealousy."

"And it's great not to think about what clothes you're going to put on in the mornings," adds Mother Hilda.

Does feminism play a part in their lives? Mother Thekla isn't sure what it is but favours a traditional family set up with a husband and children for women, while Mother Hilda believes that neither men nor women should be held back by artificial barriers and gender expectations. "In the eastern monastic tradition we are considered neither monks nor nuns," she says. "Our garb is the same as that of male monks and our offices are the same. Here we are beyond gender."

· For information about becoming a novice write to: The Greek Orthodox Monastery of the Assumption, Normanby, Whitby, North Yorkshire YO22 4PS.

Diane Taylor

The Guardian (2002)