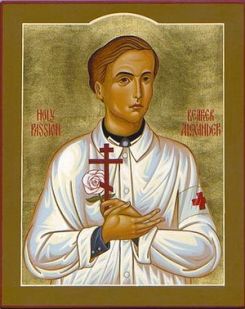

Holy Passion Bearer Alexander Schmorell.

Holy Passion Bearer Alexander Schmorell.

Alexander Schmorell was only 25 years old when he wrote a farewell letter to his parents from his death-row cell in Munich’s Stadelheim prison:

- “My dear father and mother: And so, it is not to be, Divine will has me complete my earthly life today, and to enter another, which shall never end and where we will all once again meet. May this meeting be your consolation and your hope. For you this blow, unfortunately, is heavier than for me, because I will go there knowing that I served my profound conviction and the truth. For all this I face the approaching hour of my death with a peaceful conscience.

- Remember the millions of young people who departed from this life on the battlefield—I now share their fate.

- Pass on my most heartfelt greetings to my dear friends! Especially to Natasha, Erich, our nanny, Aunt Tonya, Maria, Alyonushka and Andrei. Only a few more hours, and I will be in a better life, with my mother, and I will not forget you, I will pray to God for your consolation and peace.

And I will wait for you.

One thing I especially place into the memory of your hearts: Do not forget God!!!

Your Shurik.

Prof. Huber goes with me, and asked that I pass on his sincere good wishes.”

At five pm on July 13, 1943, Alexander Schmorell was executed by guillotine, having first made confession and partaken of the Holy Gifts of Christ.

His life had begun in the Russian city of Orenburg, a child of a Russified German, Hugo Schmorell, and the daughter of an Orthodox priest, Natalia Petrovna Vvedenskaya. Alexander was born in September, 1917, baptized to the Orthodox faith, in which he was reared. His mother died from typhus, and his father’s second wife, Ekaterina Hoffman, replaced her, but even more like a mother was Alexander’s nanny, Feodosiya Konstantinovna Lapshina, “a simple Russian peasant,” from the village of Romanovka in Saratov guberniya, who shared with the Schmorell family all their troubles and crises.

In 1921, they all emigrated to Germany, where Feodosiya continued to rear Sasha, as well as his brother and sister from Hugo Schmorell’s second marriage. Erich and Natasha were Catholic, but at home they cherished Russian traditions, the children studied Russian, read Russian literature. Alexander loved his lost homeland, but only true homeland, Russia, and his love for Orthodoxy was inseparably bound in his heart with his love for his late mother and his nanny. Faith was the main vector in his life.

Alexander often attended the Russian Orthodox church in Munich, where he met his compatriots. The young man’s letters are filled with love for his native country:

- “No country will replace Russia for me, even if it is equally beautiful! No person is dearer to me than a Russian person!

- I love Russia’s endless steppes and breadth, the forest and mountains, over which man has no dominion. I love Russians, everything Russian, which cannot be taken away, without which a person simply isn’t the same. Their hearts and souls, which are impossible to grasp with the mind, which can only be guessed at and sensed, which is their treasure, a treasure that can never be taken away.”

He was sent for a time to Austria, which had ostensibly voluntarily united with Germany, and saw even clearer that the official propaganda and the reaction of common folk were diametrically opposite. During the invasion of the Third Reich into the Sudetenland, Alexander saw that the soldiers and Sudeten Germans treated the local Czechs as occupiers. The last few months of his service, he attended medical school and, after his discharge, decided to become a doctor, so he enrolled in Munich University’s medical program. When in 1940 he was once again drafted for the invasion of France, he served in a medical unit, and his conscience remained clean: he felt that taking up arms to benefit the Wehrmacht was unacceptable.

In May, 1942, the White Rose leaflets spread throughout all of Munich, typewritten texts calling upon the people of Germany to resist Hitler and sabotage all Nazi endeavors. Christian values and culture were showed opposing pagan Nazism. People would find these leaflets, which denounced “the clique that has yielded to base instinct,” calling for the renewal of the “gravely-wounded German spirit from within,” on bulletin boards and telephone booths, in doorways and store shelves. After some time, the White Rose epistles were sent by the thousands in the mail to addressees on the territory of the Third Reich. The lofty language in elaboration of these thoughts revealed that the authors were from the intelligentsia. But no one could imagine that the fight to the death against Hitler was spawned in the city called the “capital of the National Socialist Movement,” by students from Munich University.

-

“I do not feel at home here. I am drawn to my homeland. Only there, in Russia, can I feel at home.”

He promised Nelly that he would definitely return, as soon as he completed his life’s mission in Germany. Yet this was not to be.

When the young men returned to Munich, White Rose began operations. New leaflets were published, prepared with the help of the youths’ teacher, Professor Kurt Huber. But catastrophe awaited them on February 17, 1943. That day, Hans Scholl and his sister Sophie arrived at the university with baggage filled with leaflets and distributed them throughout the classrooms and hallways. The university superintendant witnessed this and informed the Gestapo. Hearing that his friends were arrested, Alexander made an attempt to flee. But he also soon found himself in prison. By then, Hans and Sophie Scholl and Kristof Probst were sentenced to death and were executed.

Alexander was put on trial together with Willi Graf and Professor Huber. All three were given the death sentence. Did the sharp pang of failure pierce their souls? By all appearances, no. Willi Graf was also a genuine Christian—he confessed the Catholic faith, and belief in God was paramount for him. Professor Huber also made certain to relay his warmest greetings to his friends—it seems these were not people in despair.

Another letter from Alexander during his time in prison survived, one to his sister Natasha, which clearly illustrates what he was experiencing:

“Dearest, dearest Natasha!

- You have probably read the letters which I wrote to our parents, so you can probably have a good idea of my situation. You would probably be surprised if I wrote that with every passing day I am becoming calmer, even happy and joyful, that my mood is basically better than it was when I was free! Why is this? I want to tell you about this now: this whole terrible ‘crisis’ was inevitable to put me on the correct path, and for this reason it is not a crisis at all. I rejoice over this and thank God that this was given to me, to comprehend the hand of the Lord and through this to emerge onto the correct path. What did I know before about faith, about real, profound faith, about the truth, the final and sole truth, about God? Very little!

- But now I have matured to the point that even in my predicament, I am merry, calm and filled with hope, what will be will be. I hope that you also experienced this process of maturing and that you and I together, after the deep pain of separation, will come to the state of mind where you thank the Lord for everything.

- This misfortune was necessary to open my eyes, and not only mine, but the eyes of us all, all of us who have befallen this fate—including our family. One must hope that you too properly understand the way the hand of the Lord is pointing.

Give everyone my heartfelt greetings, and to you, a special greeting from your Shurik.”

The medical student Alexander Schmorell was canonized on February 5, 2012, as a locally-venerated saint of the Diocese of Berlin and Germany of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia. St Alexander became the first New Martyr glorified since the reestablishment of canonical communion between the Moscow Patriarchate and the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia.