|

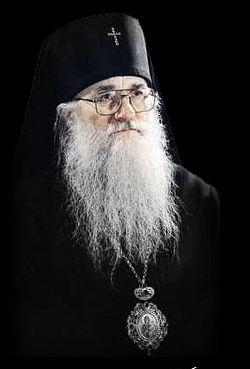

Archbishop Alypy kindly responded to my request in 2005 and composed a short autobiography. I am presenting the material as it was prepared for publication, including my brief introduction and an anecdote Vladyka told me.

Vladyka Alypy deserves more attention than he now receives. This unique material has never before been published.

I first saw Vladyka Alypy of Chicago and Mid-America as he gave a sermon during Liturgy. I remember being impressed with the simplicity with which he explained the Gospel truth. Also amazing was how text that had been read and reread many times now seemed new, unexpected and remarkable, though, again, Vladyka spoke simply, without rhetoric and almost without emotion. Vladyka made the impression of being a very kind and straightforward person.

I later learned that Vladyka not only taught Church Slavonic and Greek, but published a textbook on Church Slavonic language, and that this book is practically the only available resource on this matter in contemporary Russian. More than one generation of seminarians in Russia and abroad has used this textbook. It was also published in English and is the only book of its kind in the world.

I then found out that the church of which I am a parishioner was built thanks to Vladyka Alypy’s efforts. It also turns out that all the frescoes and icons of the cathedral (except for the antique icons) were painted by Vladyka Alypy, a wonderful artist and iconographer.

I bring to my readers’ attention the memoirs of a person thanks to whom thousands of Russians in America have the opportunity to live, believe and pray as Orthodox Christians. These memoirs are in Vladyka’s own words.

D. Yakubov

* * *

I was born in Kherson oblast in Russia, in the large town of Novaya Mayachka, on December 19, 1926. In times past this area was known as Nikolaevskaya. But my grandfather loved to called it Tavricheskaya guberniya. Novaya Mayachka is about 50-60 kilometers north of Crimea.

My father’s name was Mikhail Gamanovich, and my mother’s was Liudmila, nee Martynova. I was named Nicholas. I was the oldest child, and had three brothers and two sisters.

My father was a blacksmith by profession. He and his brother learned the craft from their father, Daniil, who owned a smithy where they all worked. My grandfather was also a carpenter.

My grandfather had a brother, Yakov, also a blacksmith and carpenter who also painted icons. Our family had a half-length icon of the Savior that he painted. The face and hands were painted in oil, and the rest—the clothing, background and flowers around the border—were made of metal foil. Truth be told, I don’t actually like foil oklady. Metal is not an appropriate material for icons, being too soft.

This was during Stalin’s reign. Soon, collectivization began as well as the raskulachyvaniye [dispossession of the kulaks—the wealthy peasant class—transl.] with all of Stalin’s wrath. My grandparents were wealthy and so were subject to persecution. For some reason he was imprisoned, where he soon died—his heart gave out.

My father’s father, Daniil, could not eke out a living and so escaped unharmed, but his brother was more successful and suffered for it. The local townsfolk respected him, and warned him: “Leave quickly, go somewhere, abandon your splendid home, and we’ll just say that you were raskulachen.” He did as they suggested, and moved to the town of Podokalinovka, finding work there as a blacksmith, and lived there until his death.

By then it was impossible to still own your own blacksmith, and so the family scattered. We lived in three towns after I was born. The last of these was Fedorovka (which no longer exists). There was only a four-year school in town. For further education, we had to go to the neighboring town, Kucheryavo-Volodimirovka, where there was an 8-year school (almost middle-school level). They taught in Ukrainian, but they also taught Russian language and literature.

First we lived on one bank of the Dniepr River, for a year, then the other… We often moved to different towns, wherever we could make do. I started school at the time. I would begin the school year in one village, then finish the year in another.

And then came the war.

It began on June 22, and by August, the Germans had arrived. They invaded quickly, since there were no natural defenses, only the Dniepr River… It was hard to resist such a sudden and powerful blow.

The German Army was well organized, well-armed, and had talented generals with WWI experience. The onslaught was great, the front quickly moved east. It was calm where we were, there were no partisans, since there was no place to hide, for the land there is flat with no forests.

Soon the Germans began to collect workers for Germany. They promised that we would have a good living and decent working conditions. Many took the bait, and the first group was made up of volunteers. But soon word came that their conditions were actually very bad. No one then wished to go voluntarily. The Germans then began to take people by force. The village elders would be told how many people they needed, and that is how I ended up among them.

The people were put in rail cars and sent to Germany. We traveled for two weeks with brief pauses. We were taken to Berlin, and from their divided up. Among us were women, who were sent to a women’s camp, and the men sent to men’s camps. They were surrounded with barbed wire, and the entrances had guard booths. Everyone from our village was in one camp together. Among those who were already there were people from Odessa and Harkov. They said that they were very badly fed, and that half of them died. I remember the address: it was Berlin, Neukolln, Russenlager 4.

Our days began at 5 am. Usually, a police officer would charge into the barracks with a rubber crop, and shouted for everyone to rise. If anyone tarried, the rubber crop would be used to hurry them up. The policeman was a Russian worker with a kerchief tied around his arm. He clearly tried to earn points with the Germans.

There were two fifteen-year-old boys with us. They would wet their beds, probably from exhaustion. We slept in bunk beds. The person in charge of our barracks assigned them a bunk bed and had them change places every night, so that they would wet each other on alternative nights, expecting that this would “cure” them of exhaustion.

We received 300 grams of bread for breakfast, a teaspoon of sugar, a thin square of margarine, sometimes a thin disc of artificial sausage and tea.

We would then be lined up, counted and escorted by a policeman (the Russian with the kerchief) to work. It was an automobile factory. At the end of the day, we were lined up again, counted, and sent back with the policeman. We were then given a thin broth, camp soup. This included rutabaga, cabbage, a bit of potato and kohlrabi. The combination varied, with the kohlrabi overripe and stringy.

I spent about two months in this camp. The commandant was apparently a Russian German. Once he visited the victory and entered the section where I worked. We were applying some kind of hard cardboard to a framework for van walls. For some reason the commandant noticed me, probably because I was dragging my feet. He asked my name and wrote it down.

Shortly thereafter, another fellow and I were sent to the dispatcher (Arbeitsamt). From there, two fellows and I were taken by some proprietor—he had a parcel of land, about 1 hectare, and a small house on the outskirts of Berlin. We were put up in this house. We were instructed to till the land between some trees and plant vegetables.

I was about 16 years old, and my companions were about three years older. I didn’t have a good idea about how to work the land, and they knew better, in general, we did pretty well.

Compared to the camp, we were much better off. There was no barbed wire, we got grocery cards, and on Sundays I could even attend church. Things could have been better, but the other fellows were not of the best character.

One of them wasn’t so bad, but the other was an orphan, and they were not averse to taking advantage of the fact that we weren’t being supervised. We had to work from 7 am to 5 pm with a lunch break. The guys decided “If the owner doesn’t come right away, we can sleep late.” But he did come and threatened us through the window. He then decided that he wasn’t going to get an honest day’s work out of us. We worked for two months, after which he sent us back to the Arbeitsamt.

From there, I was sent with my companions, I think, to a work camp to work on graves. This camp was next to a cemetery, surrounded by wooden fences, 6-7 feet high. The same wall surrounded the camp, and the entrance was guarded, but not as carefully as the previous camp.

The camp consisted of two barracks; workers lived in one, the other contained the office and cafeteria. This was in Berlin, Neukolln 2, Hermanstrasse 84/90. There were about 100 workers there.

We tended to some 30 or so cemeteries, two or three workers were assigned to each, and given money to travel there on our own. At the cemeteries, we dug graves for burials, usually on Wednesdays and Fridays, mowed the grass, tended to wreaths, swept up, etc.

Since we would travel to work alone, we were lucky. Work ended at 5 pm, and we had to return to the camp no later than 8. There was plenty of time to commute, so we had time to kill.

I was a village boy. Seeing how naive I was, the older fellows would tease me. “You know, I was digging a grave, and suddenly a corpse from the next grave snatched by foot! I hit his arm with my shovel, and kept on working…” They would be so nonchalant that I didn’t know whether to believe them or not. Then I realized what they were doing and went back to work. That was in 1943.

From 1944, the Americans and British began bombing Berlin, and as time went on, these became more frequent and more intensive, especially towards the end of the year and in early 1945. They grew bolder, and bombings occurred not only at night but during the day, without targeting anything, just carpet-bombing. Our barracks were hit with incendiary bombs and burned down. The workers were at work in their cemeteries at the time.

We were moved to the barracks-cafeteria, but there wasn’t enough room for everyone.

Some workers spent nights in the cemetery where they worked, and came to the base camp for meals. Camp life was completely disrupted: the guard booth was abandoned. The bosses only came for the day. We felt much more freedom.

I read an announcement in the Russian paper that Archimandrite Ioann (Shakhovskoy) would lead religious discussions on Wednesdays and Fridays at the church on Nachotstrasse. I tried to come on a Friday. There was no discussion. There was a moleben, however, and Fr Ioann gave a farewell speech. Soviet soldiers were approaching Berlin and they needed to quickly move west.

I approached a table where there were lithographic icons for sale. Next to it was a hieromonk named Kyprian. He began talking to me and we struck up a discussion. When I entered the church, I kissed a few icons, making prostrations before them first—this showed that I was at least somewhat religious, and so he noticed me and said “You would do well as a monk.” I responded that I had thought about that for a long time, but did not know how.

My grandfather had had religious books: the Lives of Saints, a prayer book and a few others. The Lives of Saints made a deep impression on me, and they brought back my faith in God. Of course, I had been baptized as a child and was somewhat religious, but life in the Soviet Union and its propaganda left their mark. I loved to read about the life of monks in the monastery, and I desired to follow that path myself.

Fr Kyprian suggested I visit the temporary home of his monastic brethren: “Let’s go, see how we live.” I spent the evening there and told Fr Kyprian that I wished to join. He took me to see the abbot, Archimandrite Seraphim, and interceded on my behalf. The reverend abbot first refused: “We don’t know ourselves what is to be with us, how are we to take in a young man for such a serious undertaking?” But later he agreed.

On Sunday, saying nothing to anyone for safety’s sake, I left the camp and joined the monastic Brotherhood of St Job of Pochaev—this was February 3, 1945.

The Soviet forces kept approaching Berlin, and we had to move quickly to the west—the Germans did the same, and finding transportation was very difficult. The abbot was able to obtain space in a train, and all the monks left to southern Germany and settled in a village named Feldshtetin. After some time, we moved to a different village, Sondernach. That was when Germany surrendered.

More than half of the monastics already had visas to Switzerland, and so, wasting no time, we immediately went on the road and went to Geneva. They were met by Archimandrite Leonty, Rector of the Geneva church, who found them shelter. After a few months, the other members of the brotherhood joined them. In Geneva, we all awaited visas to America.

Vladyka Archbishop Vitaly (Maximenko), the founder of the Brotherhood, made every effort to obtain visas for all of us. We had to wait a year and a half, for transportation was reserved for soldiers returning home. Archbishop Ieronym came from America, and Archimandrite Seraphim and Archimandrite Nathaniel were consecrated to the episcopacy.

The visas finally came, and Vladyka Seraphim went to America much earlier, on an airplane, and the twelve of us traveled via train through France, staying in Paris for a few days, then came to the port city of le Havre, I think, where we boarded a ship.

The brethren included Hegumen Nikon (Rklitsky), Hegumen Filimon, Hieromonk Kyprian (Pyzhov), Hieromonk Anthony (Yamshchikov), Hieromonk Anthony (Medvedev), Hieromonk Seraphim (Popov), Hieromonk Nektary (Chernobyl), Hierodeacon Sergei (Romberg), Monk Pimen, Brother Vasily (Shkurla), Brother Vasily (Vanko) and Rassophore Monk Alypy (I was tonsured to the rassophore in Geneva).

The ocean voyage was difficult, the seas were almost always choppy, and it was a two-week trip. On November 30, 1946, we arrived in New York. Vladyka Archbishop Vitaly sent some people to meet us and bring us to his diocesan residence. This was the Gothic-style church which had several available rooms.

On Sunday, we attended a hierarchal service, and the clergymen participated. Fr Nikon and Fr Pimen remained in New York to help Vladyka Vitaly, and we left the next day for Holy Trinity Monastery not far from the town of Jordanville, NY.

Holy Trinity Monastery, Jordanville, NY

In this monastery, established by Fr Panteleimon with Archbishop Apollinary’s help, and then with Archbishop Vitaly’s help, and included five monks: Archimandrite Panteleimon, Hegumen Joseph, Hieromonk Pavel, Monk James and Monk Philaret. And here we were, eleven new people, so monastic life suddenly came to life.

We settled in a big wooden house: downstairs were a chapel, kitchen, refectory and print shop, and bedrooms upstairs. The house had two additions, but with unfinished interiors. When the monastery was founded, the question arose: how was it to survive financially? The local population was comprised of dairy farmers.

Fr Panteleimon came from peasant stock, so farmland and cows were nothing new for him, and he took the chance on setting up a dairy. This provided income and also the opportunity to concentrate on publishing religious literature, which he strived to do.

He built a big barn: downstairs was for cows, and upstairs a hayloft. This barn stands to this day. By the time we came, there were 500 acres for various needs relating to the dairy: grazing meadows, sowing various crops, including corn for the silo.

Near the barn were a few other buildings: a two-storey house, a chicken house, etc. The print shop was in its nascent form, but Fr Panteleimon acquired two linotype machines already: one with Russian and English type, the other with masters for Church Slavonic and Russian typefaces, and a small press.

There was another used press which needed fixing. Fr Nektary, a jack of all trades, fixed it. Soon the periodical Pravoslavnaya Rus [Orthodox Russia] was published, edited by Bishop Seraphim. It had previously been published in Carpathian Russia, but Vladyka Seraphim did not stay long in Holy Trinity Monastery and in 1950, moved to an estate donated by Prince Serge Belosselsky-Belozersky to the diocese, where the Synod had an office, having moved from Germany to the US. He named this place the Kursk-Root Hermitage. We then began publishing books.

In 1947, Archbishop Vitaly tonsured both Vasilies to the rassophore, calling one Laurus (later First Hierarch of ROCOR), and the other Florus, and the next year, tonsured three rassophores, fr Laurus, Fr Florus and me to the mantle.

In 1948, the seminary opened.

The first year was entirely composed of monks, and as they went from year to year, they remained exclusively monastic. The building of the church had already begun, and by the time we arrived, the basement level was almost finished and had a roof, and with the coming of the next spring, construction on the upper church began.

A certain Professor Nikolai Nikolaevich Alexandrov was particularly fond of the seminary. Though he continued to teach at college, he often came to the monastery and tried to help through his connections in high places. He was already a widower by this time. Sometime later he retired and moved to the monastery.

Through Nikolai Nikolavich’s efforts, they brought bricks from some burnt-out factory and dumped them in a pile. They had to be cleaned of cement and stacked; everyone took part in this work: Archbishop Vitaly also helped frequently. These bricks were used for the internal wall of the church, and the exterior was decorated with slightly glazed, cream-colored bricks.

Nikolai Nikolaevich helped hire American workers. They worked as masons, and our monks helped them, usually Fr Sergei, Fr Laurus and Brother Leonid (Romanov), who by then arrived from Switzerland, and maybe someone else. The work was very laborious, the scaffolding was wooden: the cement and bricks had to be taken up wooden ramps on wheelbarrows. Working on the roof and the trussing, especially in the center part for the Russian-style “tent” roof, were American specialists. Copper was applied to the tent roof, and the rest with some sort of tiles. As far as the interior is concerned, because of the lack of resources, we relied on our own efforts.

The plans of the church were drawn up by the architect Verkhovsky, but for the practical application of these plans, another architect would visit who showed Nikolai Nikolaevich what to do. The latter passed it on to our laboring monks, who tried to follow instructions the best they could. Two-by-fours were nailed into the walls, 40 centimeters apart, and then everything was insulated with tar. Then they used the lath and plaster method to finish the interiors. Because of the inexperience of the monks, the plaster would often collapse into the wall. We should have applied fiberglass insulation first, but none of us knew anything about this, and for some reason, the architect didn’t recommend it….

After a few years, some Russian refugees, mostly from Germany, began to resettle in America. Fr Archimandrite Iov, a member of the St Job Brotherhood, who remained in Germany to minister to Russian refugees there, set up a small monastery near Munich, and he gathered some residents: some wished to join the monastic life, others weren’t sure, or more likely were hoping that the Church would help them get to America.

Fr Iov sent us a whole group of such people, which included monks and trudniki [volunteer lay laborers in a monastery]; the latter were given instructions that they were obliged to work at the monastery for at least a year.

In addition to this group, other new members joined; some came to live the monastic life, others to study at the seminary, some of whom were tonsured during or after completion of their studies. The number of residents grew, more seminarians enrolled, and we needed room.

As a result, we began to build the main monastery building. We built the reinforced concrete basement ourselves. Fr Nikodim, an engineer by training, then took over. Nikolai Nikolaevich also participated, as Americans built the walls and roof, while we finished the interior ourselves. The building consists of four floors, the top floor being a mansard, with windows protruding through the sloped roof.

A few years passed, and the need arose for a seminary building. Nikolai Nikolaevich took up this project, and soon the building was completed. He also succeeded in obtaining state recognition of the seminary program. This gave us the opportunity to sponsor seminarians from abroad. Eternal memory to servant of God Nikolai! Later other buildings were added, some of them after I left.

All of the monastics participated in some kind of work; the locals and the visitors worked a great deal, to the best of his abilities. Thanks to all this work, the monastery exists to this day. I only recalled some of those who contributed, but all of this work was supervised by and had the blessing of Archbishop Vitaly. After his death in 1960, he was replaced by Bishop Averky, who arrived at the monastery as an archimandrite, being consecrated to the episcopacy a few years later. He was then elevated to the rank of archbishop, and died in 1977.

As far as I am concerned, at first I was assigned kitchen duty to help Fr Philaret. I worked there for over two years, first as a helper, then independently. When help arrived, I was relieved of this duty, especially since Fr Kyprian needed help painting the church frescoes. I don’t remember how many years I worked on painting the church, especially since the egg tempera we used turned out to be defective. When acrylic paints became available, we repainted everything.

Even before studying at the seminary I loved Church Slavonic. When we studied this subject, I tried not to miss a lesson; it was taught to us by Protopriest Michael Pomazansky, a very well-educated person, having graduated from Kiev Theological Academy. He had a good sense of grammar and was a gifted teacher. He also taught us Greek and a few other subjects.

After graduating Seminary and receiving my diploma, I was offered the position of teaching Church Slavonic.

After teaching for a few years, I composed the book Church Slavonic Grammar. Holy Trinity Monastery published it in 1964. A second edition with some edits was published in 1984. Protopriest John Shaw translated my book into English, which was published by the monastery in 2001.

I made a few corrections in the English translation. Fr John speaks several languages, and so was able to take on this daunting task. I owe him a debt of gratitude. I was very pleased to learn that my textbook is being used in Russia.

I think there were two reprints in Russia, in the 1990’s an edition of the 1964 version came out. I was somewhat upset, since I knew the 1984 book was an improvement, having polished it and added a few things… But it was explained to me that copyright laws did not apply to books from 1964, so they chose this edition, so I couldn’t sue.

I had no intention of taking anyone to court. On the contrary, I was very happy that my book could be of use, that it is being used for studying, that it found an audience…

Our years abroad passed, and Orthodox life, our church life, continued to improve under the guidance of our senior archpastors, to the extent possible. Unfortunately, many of us passed on to a better world, and they needed to be replaced. But where would they come from? Sometimes we would take widowed priests into the episcopacy, but often monks from Holy Trinity Monastery. Archimandrite Laurus was consecrated Bishop of Manhattan and served as the Secretary of the Synod of Bishops for many years. A few other people were likewise consecrated. And so it was with me.

Archbishop Seraphim (Ivanov)

Archbishop Seraphim of Chicago and Detroit asked the Council of Bishops for a vicar bishop. He had suffered a stroke as a result of high blood pressure, which he had ignored, and his right side was partially paralyzed. Gradually the paralysis faded, but he still had to drag his right foot somewhat, and so he always used a walking stick. It was difficult for him to tour his diocese.

The lot fell to me, and the date of October 20 was settled on, in Chicago, for my consecration. This was a Sunday, when they moved the Cathedral feast day of the Protection of the Most-Holy Mother of God.

On the appointed day, Metropolitan Philaret, Archbishop Seraphim, Archbishop Vitaly and Bishop Laurus celebrated Liturgy, during which I was consecrated Bishop of Cleveland and Vicar of the Diocese of Chicago and Detroit.

At one time back in 1945, Vladyka Seraphim, who was then an archimandrite and head of St Job of Pochaev Brotherhood, received me, an Ostarbeiter [“Eastern worker” under the Nazis—transl.], as a member of his community, and now by the will of God I was to be his assistant. No good deed goes unrewarded.

Vladyka Seraphim visited the main parishes of the diocese with me, to introduce me has his vicar, after which he left he visits to parishes to me alone.

But Vladyka Seraphim was still very active, managing the life of the Cathedral and of Vladimirovo, attended annual parish meetings, convened diocesan assemblies, and traveled to New York for sessions of the Synod of Bishops, etc.

His final three years he suffered great weakness, so he moved to Mahopac and soon reposed, in 1987. Eternal memory to him! Soon I was appointed Ruling Bishop of the diocese.

________

I have been in Chicago for 31 years now.

At first there was a building, in decent shape, and the church was downstairs. An Orthodox cross still stands there. Then we bought a house. Only one deacon lived by the church, in a good room.

At first our church was in the city, then we moved here and sold our church to Macedonians. We were very happy that they were the buyers, since they are also Orthodox. It would be a shame if it were turned into a dance hall.

The Savior. Fragment of a fresco in the cupola of Protection Cathedral in Chicago. All the Cathedral’s frescoes were painted by Vladyka Alypy.

When we voted—80 voted for buying some land and moving, 7 were against. The old people complained “How will we get there?” So they stayed behind, and started to attend the Macedonian church. So as it turned out, we gave the Macedonians a church complete with parishioners. They serve in the Church Slavonic, but they have an accent, so you have to listen carefully to understand.

Vladyka Seraphim was here—when I arrived, the parish was celebrating its 25th anniversary. But I didn’t like it, because the neighborhood was bad. There were many hooligans who scrawled graffiti on our church, and it was difficult to stop. We would come to church and they would be sitting on the steps. Sometimes they would snatch purses. That is why I wanted to move. And there was little parking for the parishioners, so they had to park in the city. It was dangerous. And public transportation in America is infamous for being infrequent, especially on Sundays, and the routes are inconvenient.

In short, it was a problem. This was in 1974, right after my consecration. There was one priest at first, then another. Fr John was there, but he moved to Milwaukee. Vladyka Seraphim was hurt somewhat that I wanted to move, he would say “Let me die first, then you can move.” But then he consented. He even established a fund. When we bought land, we already had the money, this was in 1986.

At first it was hard, since the local Americans, having learned that Russians wanted to move here, would shout “The Russians are coming! The Russians are coming! Communists are here!” They always thought that Russians are by definition Communists.

An American drew up the plans for the church. It was to be a tall one, 50 feet high, with a cross reaching 60 feet up. But the locals did not want to allow us to exceed thirty-five feet—so they held a meeting and tried to stop us.

The meeting was in City Hall, and some 80 people came to object. They could not tell us that we couldn’t build a church, but they were stubborn, “You can build 35 feet, no more,” using this to try to stop us from building our church.

One of them spoke: “I am a Vietnam veteran, I live in the area, and if they build a church that high, it will disrupt my television reception, all the channels will be scrambled.” There were many such objections, a lot of people made up excuses to stop our plans. We were intimidated and considered abandoning the project. But we made a down payment, and were prepared to ask for a refund.

A Greek man had been the owner, and he apparently already spent the money. At the time, under President Carter, the value of the dollar fell, banks paid 10% interest. So the Greek did not want to refund the money. So I decided to move ahead, and buy the parcel.

My idea was this: even if we do not build our church, and are forced to sell, I will accept the financial loss, but there was another consideration: property values were rising, maybe we would actually profit. So I bought the property. There were key people who were prepared to make the move here, so we paid the seller the entire amount. Some were hesitant: “We lost our money, and Vladyka Alypy bought himself a summer home!” Now they’ve forgotten all about that and brag “We built this church!”

In 1983, Vladyka Seraphim moved to Vladimirovo, a hundred miles northwest of Chicago. They searched for a parcel of land that would serve as a children’s summer camp, and found a 70-acre site with a pond. Vladyka Seraphim had the idea for a camp. And so they have had camp there for 35 years already. Vladyka Seraphim lived there until his death.

He died in 1987. He didn’t live to see our cathedral, being too weak to travel. I don’t know if he would have been very happy, because all we had then was the house and shed.

Thank God, we have already built the cathedral and a church hall, and a school… The older generation has retired, they have their own concerns how, but their children are growing and I hope they take over.

* * *

Now (2005), I have been a part of the Chicago and Detroit Diocese as a Vicar, then Ruling Bishop, for 31 years. The last three years, due to illness, I almost don’t participate in diocesan life, which is administered by my own Vicar, Bishop Peter.

Over this time, two new churches were built: in Cleveland (1979-1981), and the Cathedral in Des Plaines, near Chicago (1990-1991), I painted the frescoes for both. Fr Theodore Jurewicz and Alexander Chistik helped me in Cleveland. Several years were devoted to this, 1982-1988), and the painting of the Cathedral’s frescoes took several years, 1991-2002.

I also painted the frescoes for the church in Denver, CO: the Judgment Day for the back wall, which was painted on canvas and glued to the wall with the help of Protopriest Peter Burlakov, and with his help, the Divine Liturgy painted for the altar, on stiff panels.

Over this time, several new parishes were added. Unfortunately, the number of old parishioners, of the first and second emigrations, has fallen, some grew old, others passed away, but since 1991, new immigrants have begun attending our churches, those from Russia in search of work. It is our duty to draw them to church life.

As far as I am concerned, personally, I can only speak of my feebleness. In 2002, misfortune befell me: I decided to saw off a branch from a mulberry tree near the church which kept dropping its berries on the path, causing a mess. I threw caution to the wind, the branch fell on knocked the ladder out from under me, and I fell to the asphalt, injuring my back, causing paralysis in my legs.

Gradually the ailment has improved, but I can only move around with a walker, and not very far. I hope for the best, relying on God’s will…

Thank God, my health is gradually returning. Only my legs are troublesome because of nerve damage. Many think my recovery is miraculous—things seemed hopeless at first.

And that is the story of my life.

Archbishop Alypy, July 30, 2005.

* * *

Vladyka Alypy lives in the small house near the Cathedral and enjoys complete obedience by his parishioners. “A real monk,” is what they call him.

Vladyka participates in Liturgy to the best of his abilities, and delivers a sermon every Sunday.

Alpha and Omega Almanac, 2009.