Last year a book was released by the artist Andrei Yakhnin, entitled Anti-Art. Notes of an Eye-Witness, dedicated to an analysis of the sources of contemporary art, about which the author, formerly an avant-garde artist, knows firsthand. In his introduction, Yakhnin wrote about “the need to make sense of this system-forming phenomenon of modern culture, which is aggressively trying to dominate the world. We cannot ignore this domination because it inevitably leads to the existence of a cultural-civilizational reservation. The Orthodox Church has been the nucleus around which Russian culture and civilization formed, and obviously must not allow itself to be locked up in such a reservation. Therefore, we who declare ourselves members of the Orthodox Church must to the best of our ability try to analyze the processes taking place in modern culture, formulating and arguing our own position.”

Recent events in Russia, such as the highly disrespectful demonstration in the Christ the Savior Cathedral by a female punk rock group that was characterized by supporters as a display of modern art, only serves to confirm Yakhnin’s position. Pravoslavie.ru/Orthodox Christianity has therefore decided to publish portions of Yakhnin’s book, Anti-Art. Notes of an Eye-Witness.

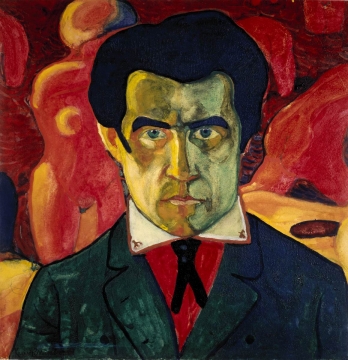

Kasimir Malevich[1]

|

| Kasimir Malevich. Self-portrait. 1910. |

Malevich had the marks of a Mephistopheles, beginning with an external appearance similar to that literary hero and ending with a conscious and systematic confession of evil as a characteristic of his own nature. The author of the “Black Square” walked systematically, step by step, to this confession; and this was not an unexpected “vision” or fact of having made a pact with dark powers—which leads us to think that evil, envy, and hatred wrapped in a pride morbid to the point of schizophrenia were ontologically present in the artist from the very beginning of his “creative” work.

Malevich was born in a provincial Polish Catholic family in the Ukraine. Although he was partly of peasant origin he headed for the city at a young age, where revolutionary life was already fomenting, filled with the spirit of terrorism both politically and intellectually. Once in Moscow, Malevich immersed himself in the international milieu forming there and systematically studied all the stylistic trends of that time, from impressionism to cubism and futurism. This study was not simply of external stylistic exercises or even an interested delving into the essence of each trend. Malevich strove to systematically make short work of the latest styles in art, picking them up at with amazing metaphysical depth and revealing in the process his own secret kinship with dark spiritual elements, the involuntarily medium of which some artists at times became.

In explaining, for example, the works of the impressionists, he wrote, “When an artist draws, he transfers the paint like a plant, and the object disappears, inasmuch as it is no more than basis for the visible paint by which the object is drawn.”[3]

This was not just the evolution of the artist, “in the course of which he systematically radicalized everything that came into his path”.[4] This could most likely relate to the general spiritual plebianism that was then taking over the strategic upper echelons of culture, and its striving toward its own first image, one of whose guises was Malevich himself. He as if gradually stored up a strategic reserve of hatred, not only accumulating in his creative word all the negativity of the latest styles, but also giving birth to his own rather creepy symbioses, such as cubofuturism.[5]

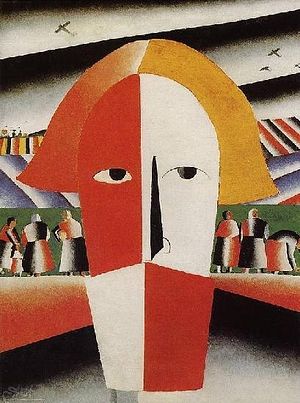

|

| Kasimir Malevich. Head of a peasant. 1928. |

In general, it evokes astonishment (mixed with a natural spiritual repulsion) how open, systematic, and surgically precise was Malevich’s operation performed on everything that bound traditional culture with Christian sources. Knowing iconography well, he created all his works on the principle of mixing iconographic Christian symbolism with satanic symbolism. For example, he had fully conscious knowledge of the term, “the all-seeing eye” as a certain specific image that is hidden from the uninitiated and looks out from the picture at the viewer. Jean Claude Marquade[7] once evaluated this “invention” of Malevich: “On an icon, this eye belongs to Christ: His eye is open wide and looks out from the deeps of the soul through the visible world, discerning true reality. However, in the “Portrait of I. V. Kliun” this “eye” characteristic of icons, an iconographic archetype called the “all-seeing eye”, endures a dislocation. The perspective becomes “abstruse”. On the drawing, one part of the eye is displaced with respect to the other, this eye is forced against the axis of the nose, and depicted in the form of an elongated parallelepiped. Because of this the parabolic meaning of the double vision becomes clear: an inner and outer eye, seeing vision and knowledge, perception and comprehension…”[8]

In connection with this, we must also recall the exhibition called “010” in the gallery of Nadezhda Dobychina, where Malevich set up a real “home iconostasis” out of suprematist canvases, with his “Black Square” in the main place.

The artist himself many times referred to his suprematist experiments in the realm of traditional icon painting, called the sources of his red and white squares was in the colors of the “Novgorod school of icon painting: the horse’s white breast and the bright red garments of St. George the Trophy Bearer, or the white episcopal garments, sprinkled with black crosses that St. Nicholas has on his vestments.”[9]

This, not only culturophobic, but militantly antitheistic, anti-Christian position of the artist is shocking, but explains much—for example, the very fact of Malevich’s long-term cooperation with the Bolsheviks along with his like-minded colleagues who were also his competitors, such as Tatlin, Rodchenko, and others. And in light of similar general evaluations of Malevich’s creativity, the rhetorical question of our day is: If modern art has its beginnings in openly satanic sources, can it in any way witness Truth and Light?

The sect of modern art as an actively antitheistic movement[10]

|

| Bill Viola. Video installation in the Church of San Gallo. |

One of Bill Viola’s latest well-known works was a video installation in the Church of San Gallo.

Within the program of the Venice art biennial in 2007, the artist placed enormous monitors in the church’s altar niche. With soft, psychedelic “ecomusic” consisting of the rustle of running water and crackling fires, stationary human figures slowly appear with increasing brightness and clarity on the monitors and then again fade out. The figures, which were in both color and black and white, were not of a neutral character, but were emphatically aggressive despite their immobility. One figure alone—a young man in a black t-shirt with a struck-out satanic cross around his neck and lowered eyes—was enough to express this aggression. This medium so permeated with dark energy placed in the sacred space of a Christian church created the incredible effect of an invisible presence of an enemy spirit, grinning with satisfaction as it watched an insanely proud man who wants to assert himself at the expense of the Redeemer.

Viola’s psychedelic “new age” motifs are linked with his interest in eastern occultism. Viola himself confirmed this in his interview at the biennial, in which he related that over thirty years ago, during his trip to Japan, he became a student of the Zen master Dayen Tanaka. The artist admits his professional interest in Zen and Sufism, along with Catholic mysticism.

This indiscriminate circle of interests speaks of the artist’s ontological Gnosticism outside of Christianity. The ancient cult of satan had its beginnings in Gnosticism during the first centuries after the Birth of Christ. This cult has come down to our own age under different guises as certain “new age” movements. However, its essence is the same.

The new age writer David Spangler[11] in his book, Reflections on the Christ writes, Christ is the same force as Lucifer... Lucifer prepares man for the experience of Christhood. (He is) the great initiator.... Lucifer works within each of us to bring us to wholeness, and as we move into a New Age ... each of us in some way is brought to that point which I term the Luciferic Initiation ... for it is an invitation into the New Age. (p.44-45).

Another postmodern artist, Pipilotti Rist,[12]demonstrates the same kind of free association with occult symbols and pagan images within the traditional space of a Christian church.

The exhibition of her video installation also took place at the Venice biennial, in the church of San Stae. Having first scattered pillows on the floor of the church for the viewers, she gave a video projection to the dome. The picture showed a group of naked women shot from beneath who move across the dome, sitting and dancing. Such an open expansion of primitive paganism in the sacred space of a church evoked some mild protest from the small religious community in the city that was quickly stifled by an aggressive press and the artistic establishment of the biennial.

In connection with this, we recall the exhibition in one Moscow church[13], which quite awkwardly tried to support the tendency that already exists in Europe of sneaking modern art into traditional church spaces. The awkwardness of this, in my opinion, consists not in the fact that the exhibition took place, but in the feebleness of the arguments put forth in defense of this project. If in the West this process is definitely interpreted by the artists themselves as expansion into previously closed sacred realms of Christian religious awareness and culture with the aim of subjugating and destroying Christianity, then in the case of the Moscow exhibition we hear only unconvincing proclamations about the need for dialogue between modern art and the Church. All the while the spiritual platform itself, upon which they presume to have such a dialogue, as well as its actual final goal remain a mystery.

Developing further the theme of the revision of Christian culture by postmodern art, we will touch briefly upon the more radical wing of contemporary art that is working in this zone. We touch only briefly because a more detailed description of this phenomenon could psychologically traumatize any normal person by acquainting him more closely with this so-called “art”.

Of the more harmful and dangerous of these radicals we have to note firstly the representatives of the so-called Viennese Actionism of Herman Nitsch,[14] whose exhibition, by the way, was shown recently in Moscow.

Nitsch’s performances and stationary exhibitions, the “Theater of Orgies and Mysteries” presents an illustration of Gospels events (using Christian symbolism, including the Crucifixion), immersed in a horrible bloody bacchanalia against the background of the naked bodies of extras who depict an uninhibited orgy. The blood used is both artificial and real, for which animals and birds are sacrificed. This sickening pagan mystery goes far beyond the boundary of good and evil, and is a demonstration of extreme satanic possession at which the image of humanity is completely lost.

Another “master” of this kind of “art” is Oliviero Toscani,[15] who works mostly in the area of postmodern photography often used in advertising. His widely distributed photography, advertising a clothing company show Catholic nuns and priests kissing. These advertisements have even appeared in Rome, at the very gates of the Vatican, which brought a great scandal—leading to greater interest in the company’s products. As we can see, antichristian themes are also working ever more successfully on the flywheel of mass production.

<…>[16]

The sickening evidence of the decomposition of modern culture and the human personality shown in antichristian postmodern art make occultism of the “New Age” its spiritual partner and brother. Truly, working in parallel spheres on the “project” of modern post-Christian civilization, the New Age movement and postmodern art, competing in the use of technology for the destruction of Christian culture and the Christian Church, mutually supplement each other and actively exchange their reborn ideas and thoughts. This exchange is taking place not only in the area of modern culture, but also in mass communications and on the internet. All this painstaking and generally organized work is dedicated to the same thing—the destruction of Christianity, the Church, and in the final analysis, to the erasing the very memory of God from cultural codes of today’s civilization. It was precisely this task that was articulated in the article “The Extermination the name of God” by the guru of postmodernism, Jean Baudrillard wrote that, “To sum it up, this is, on the level of the signifier, of the name it incarnates, the equivalent of putting God or a hero to death in the sacrifice. Following this, the animal totem, the god or the hero circulate, disarticulated, disintegrated by its death in the sacrifice (eventually torn limb from limb and eaten), as the symbolic material of the group's integration. The name of God, torn limb from limb, dispersed into its phonemic elements as the signifier, is put to death, haunts the poem and rearticulates it in the rhythm of its fragments, without ever being reconstituted in it as such.”[17]

The desire for a culture and civilization outside of God, the desire to occupy His place, which makes modern art one of the most secretive esoteric sects, is a serious danger to that remnant of traditional culture that still preserves its Christian roots and has remained free from the domination of sectarian culture present in the hierarchy of contemporary art. It should view its place on the periphery of the modern process of development of today’s civilization as direct and clear proof that God’s truth is not of this world, and not as historical and social injustice. After all, in the final analysis the destruction of Christian culture is catastrophe for everyone. We can only sadly repeat the words of King David: The fool has said in his heart, there is no God (Ps. 13:1).