SOURCE: ncregister.com

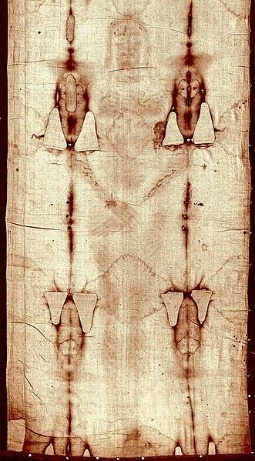

Front image of the Shroud of Turin

Front image of the Shroud of Turin

A new book written in Italian, Il Mistero della Sindone (The Mystery of the Shroud), by Giulio Fanti, professor of mechanical and thermal measurement at the University of Padua’s Engineering Faculty, and journalist Saverio Gaeta, states that by measuring the degradation of cellulose in linen fibers from the shroud, two separate approaches show the cloth is at least 2,000 years old.

And while Fanti’s methodology has been questioned by others, the book also states that another series of mechanical tests, designed to measure the compressibility and breaking strength of the fibers, corroborated these findings.

According to Italian journalist Andrea Tornielli, the three separate tests, when averaged, showed the linen fibers of the shroud to have been woven into cloth around 33 B.C., give or take 250 years, thus nicely bracketing the year 30, when most historians say Jesus died on the cross.

In response to email questions, Fanti explained that he used a pair of established techniques, infrared light (Fourier Transform Infrared, or FTIR) and Raman spectroscopy, to measure the amount of cellulose in shroud fibers given to him by microanalyst Giovanni Riggi di Numana, a participant in the 1978 Shroud of Turin Research Project (STURP), as well as the controversial 1988 carbon-dating tests of the shroud. Riggi died in 2008, but the fibers were transferred to Fanti through the cultural institute Fondazione 3M.

According to Fanti, both the infrared light beam and the red laser of the Raman spectroscope excite the molecules of the material, and the resulting reflections make it possible “to evaluate the concentration of particular substances contained in the cellulose of the linen fibers.” Because cellulose degrades over time, he said, “it is therefore possible to determine a correlation with the age of the fabric.”

Fanti compared his results with nine other ancient textiles of known provenance, with ages from 3000 B.C. to 1000, and two modern fabrics. Having taken into account differences resulting from the various environments and pollutant levels to which the fabrics were exposed, he’s confident any remaining unaccounted variables are included in the 500-year window within which he placed his primary date of 33 B.C.

Doubts

Because of the manner in which Fanti obtained the shroud fibers, many are dubious about his findings. The shroud’s official custodian, Archbishop Cesare Nosiglia of Turin, told Vatican Insider, “There is no degree of safety on the authenticity of the materials on which these experiments were carried out [on] the shroud cloth.”

Responded Fanti, “He did not read my book, and especially its appendix in which the traceability of the samples is clearly shown.” According to Fanti, Riggi unstitched the backing cloth that was sewn onto the shroud in 1532 to protect it after it was damaged in a fire and vacuumed some of the dust that had accumulated between the two sheets, catching this residue on a series of filters.

It was on fibers from “filter H” that Fanti did most of his work. “I discovered a relatively simple technique to detect which linen fibers were from the shroud,” he said, “based on cross-polarized light used in a petrographic microscope. The shroud fibers show a coloration like a coral snake, probably because in the original preparation of the fibers they were beaten with rods.” More recent fibers, Fanti said, were prepared differently and therefore appear differently under a microscope.

“[Fanti’s work] is new science,” acknowledged Barrie Schwortz, a lifetime student of the shroud and part of the original STURP investigation that undertook its first extensive scientific examination in 1978. “But it would be more convincing if the basic research had first been presented in a professional, peer-reviewed journal. If you’re using old techniques in new ways, then you need to submit your approach to other scientists.”

Fanti has announced that “an international professional journal,” presumably peer-reviewed, will soon publish a paper in which he defends his scientific approach. But, Schwortz notes, he has not yet announced which journal will publish his work.

A Skeptic’s Arguments

Joe Nickell, senior research fellow of the Amherst, N.Y.-based Committee for Skeptical Inquiry, says the Shroud of Turin is neither a matter for science nor faith, since it was known to be a fake from the time it appeared in the 14th century.

Asked to list the reasons he believes the shroud is a fake, Nickell argues that its shape is wrong, according to both Gospel accounts and ancient Jewish burial practices. “Simply draping the cloth under and over the body is from the Middle Ages,” he said.

He notes other problems with the shroud image, including the hair lying close to the head, “when it should be splayed out,” and the unnaturally elongated shape of the body “more like French Gothic art than real life.”

Nickell also refuses to accept that any record of this particular shroud can be found before it showed up in Lirey, France, around 1350.

Even then, he notes, two succeeding bishops from the area pronounced the shroud a fake, the second purportedly producing the artist who created it. “These are claims by bishops, not the village atheists,” noted Nickell.

Nickell also relies heavily on the work of the late microscopist and shroud skeptic Walter McCrone, who, Nickell claimed, was part of the original STURP team from 1978 and was only driven out when he got the “wrong” answers from his research. “McCrone found scores of problems with the image,” he said, “including that the blood stains were unnaturally bright.” According to McCrone, the blood stains, as well as the image itself, seemed to be made from a pigment of “red ochre and vermilion tempera paint.”

In fact, McCrone was never part of the STURP team, and others who viewed his attempt to create a similar image using this kind of paint instead found it entirely unconvincing as a replica of the shroud.

The actual STURP team members themselves were convinced by their joint investigations that the shroud was indeed a burial cloth of inexplicable origin, stating in a summary of their final report: “We can conclude for now that the shroud image is that of a real human form of a scourged, crucified man. It is not the product of an artist. The blood stains are composed of hemoglobin and also give a positive test for serum albumin. The image is an ongoing mystery, and until further chemical studies are made, perhaps by this group of scientists, or perhaps by some scientists in the future, the problem remains unsolved.”

But Nickell maintains the strongest argument against the shroud is the 1988 carbon dating. Despite violations of many previously-agreed-upon protocols, and questions about the decision to take test samples from the outer edge of the cloth and the demonstrable incompetence of several leading participants — all of which have left permanent doubts about the testing’s accuracy — the fact remains that three separate laboratories (in Arizona, England and Switzerland) produced test results that put the shroud’s earliest possible origin at the tail end of the 13th century.

“The three laboratories got dates so close together that I compare them to three arrows hitting the same bull's-eye,” Nickell said.

While he rejects the authenticity of the Shroud of Turin, Nickell insists that a shroud might be found that he could accept did come from the tomb of Jesus Christ, but its history from the grave to the present day would have to be completely documented. “And it could not have an image on it,” he added. “That implies a miracl, and as such takes it out of the realm of science.”

Rebutting Nickell

“Joe Nickell won’t even debate me any more,” said Schwortz, who participated in the original STURP team as a Jew who did not believe Jesus Christ was the Messiah. “Joe’s main argument is that faith should never be combined with science, and because I’m not a believer, I take away his biggest weapon.”

As a Jew, Schwortz said, he came to the study in 1978 as a total skeptic.

“But our science proved the image is not a painting nor a photograph,” he said. “And, finally, after 18 years of study, the evidence convinced me this cloth wrapped the historic Jesus.”

Most convincing, Schwortz said, is the image’s unique character. “People try to make things that look like the shroud,” he said, “but no one has come close. Nor has anyone been able to suggest a mechanism that could create an image with this specific set of physical and chemical properties.”

The spatial information embodied in the image means that it had to be created “by some sort of interaction” between the cloth and a body. “Good luck trying to duplicate that,” he said.

Schwortz ridiculed some of Nickell’s other arguments. “He hasn’t noticed that the hair is tight to the head because the man on the shroud has a ponytail,” he said. “Plus, it was stiff from being soaked with blood and sweat.”

Schwortz is particularly scathing regarding Nickell’s emphasis on McCrone’s finding of red (iron) ochre in a sample of the cloth. “Of course he found iron ochre,” he said. “When you ret [soak] flax, it breaks down fibrous material and in the process absorbs iron from water. We found pure, red iron oxide on the shroud, but that’s not pigment, which would have to be mixed with cobalt or manganese. The iron has nothing to do with the painting and everything to do with the way the linen was made.”

And Schwortz does not regard the carbon dating that seems to indicate the shroud has a medieval origin as definitive. “At one point in my life, I would have said that dating was critical,” he said, “but the results were counter to all other evidence.”

He further notes that such dating often produces anomalous results that are dismissed, when other evidence is more compelling. “But in the case of the shroud,” he said, “the skeptics have kept the outlier [the dating] and thrown away the other evidence.”

“Think about it,” he said. “Only one guy in history had these specific tortures applied, and it was done in a time when we know it was a Jewish custom to mop up the blood and place it with the body. All of this is on the shroud. Again, according to the evidence, there was no paint, no brush marks, no scorching used to make this image. The only way that image and those blood stains could get there was by some sort of interaction between cloth and body.”

Holy Saturday TV Appearance

Authentic or not, the Shroud of Turin continues to demonstrate a remarkable ability to remain in the news, as witnessed this Lent and Easter. Following Fanti’s new book came the historic television appearance on Holy Saturday, sanctioned by Pope Benedict XVI as one of his final papal actions.

In conjunction with the TV broadcast, a Church-sanctioned app called Shroud 2.0 was launched for tablets and smartphones. The app permits viewers to scroll over a digitized high-definition image of the shroud and study it for themselves.

When Pope Francis opened the March 30 television broadcast on Italy’s RAI Uno television network with a personal reflection, he steered clear of any implied pronouncement on its authenticity.

Nevertheless, he did affirm that the shroud invites viewers to “contemplate [the suffering of] Jesus of Nazareth” and stated, “The face in the shroud conveys a great peace.”

Said the Holy Father, “It is as if it let a restrained but powerful energy within it shine through, as if to say: ‘Have faith; do not lose hope; the power of the love of God, the power of the Risen One, overcomes all things.’”

Shafer Parker Jr. writes from Calgary, Alberta.

Key Facts About the Shroud of Turin

· Purported burial cloth of Jesus.

· A linen shroud covering the dead body of Jesus is mentioned in all four Gospels.

· The cloth, a rare 3-to-1 herringbone twill weave of hand-spun linen, 3 feet 7 inches by 14 feet 3 inches, bears the detailed front and back images of a man crucified in a manner identical to that of Jesus of Nazareth, as described in the Scriptures.

· Displayed publicly in Lirey, France, in 1355, considered by many to be the first documented appearance of the shroud. It was brought to Turin in 1578, its home to this day.

· In 1988, the shroud’s credibility suffered a setback after three separate carbon-dating tests placed the origin of its linen fibers no earlier than the 13th century. Since that time, several experts have testified that the tested fibers, taken from the outer edge of the cloth, were contaminated through repeated handlings and likely not part of the original cloth.

· Strong evidence indicates the shroud was in Europe hundreds of years before it appeared in Lirey. The Pray Manuscript, the earliest surviving text in Hungarian, is dated to 1192 and features drawings that are clearly influenced by the shroud. The artist not only arranges the body of Christ in precisely the same manner, he is being enveloped in the same sort of shroud, in which the artist even imitates the herringbone weave of the cloth and includes some of the burn holes still extant.

· Other scholars have traced the shroud back to Constantinople at the end of the first millennium, confirming its Middle-Eastern provenance and casting further doubt on the theory that it is a medieval forgery.

· First photographed in 1898 by Secundo Pia, who also discovered the image is a negative.

· The human image on the shroud rests on the outer fibers of the linen weave, in a layer 100 times thinner than a human hair.

· Uniformly dark pixels make the image similar to a random halftone, with more pixels per area in darker portions.

· The sharply bounded pixels that make up the body image cannot be duplicated by any known process today.

· In 1976, a VP-8 Image Analyzer confirmed that the image, unlike any regular photograph, drawing or painting, is dimensionally encoded, able to yield spatial information about the head and body that lay beneath.

· Darkness on the cloth is inversely proportionate to the body surface’s distance from the cloth — up to a limit of 3.5 cm. This results in the 3-D nature of the image.

· The image on the shroud presents an X-ray-like picture of the skeletal system, particularly displaying the bones of both hands, the left wrist, the skull and front teeth and some of the vertebrae.

· Blood stains are exactly correct as modern medicine would expect to see from a crucified victim.

· The nail holes are placed not in the palms, but in the wrists, a position necessary to support the full body weight of a crucified man, but a bit of information unknown to medieval artists.

· Scourge marks (approximately 120) have UV response around them, consistent with the presence of blood serum.

· Travertine aragonite dust, as found almost exclusively in the vicinity of Jerusalem, is found on the feet, knees and nose.

· In 2002, Dr. Mechthild Flury-Lemburg, former curator of the Abegg Foundation textile museum in Berne, Switzerland, and a world authority on ancient textiles, announced that the weave and style of the materials were from the Dead Sea area and could only have been woven in the period from 40 years before the birth of Christ up to 70 years afterward.

· In 2005, chemist Raymond Rogers, a fellow at the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico and an original member of the Shroud of Turin Research Project (STURP), publishes peer-reviewed research in the journal Thermochimica Acta, showing the carbon-14 testing from 1988 was, in fact, not done on the original burial cloth, but, rather, on a patch that in the Middle Ages had been cleverly re-woven into the border area, thus creating an erroneous date for the actual shroud.