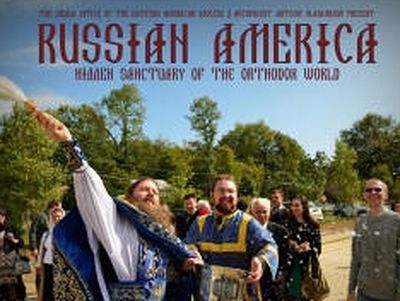

Latyntsev V. Rev. Herman of Alaska blesses the Court of the Russian-American Company

Latyntsev V. Rev. Herman of Alaska blesses the Court of the Russian-American Company

Orthodoxy came to America in four waves. The first wave was by missionary activity in Alaska, a land that belonged to Russia at the time. Russians began trading with natives for fur in the 18th century, and a very successful fur trading company was established on Kodiak Island—the Russian-American Company—along with a school for the indigenous people. Over time, under influence of the fur traders and with quite a bit of intermarrying, many natives converted to the Orthodox faith.

With a slew of Orthodox converts and no priest to care for them or administer the sacraments, the fur traders appealed to the Russian Holy Synod of Bishops to send a priest. Catherine the Great, the Empress of Russia, decided that it would be better to establish a genuine mission to the local peoples, not merely send a stopgap priest.

In September 1794, a small group of monks arrived on Kodiak Island to spread the Gospel to the natives. And though it was very successful, it was not an easy mission. The monks were upset with the way the Russians behaved, and how they treated the native population. Often, the natives’ greatest advocates and protectors were the missionaries.

Over the years, a number of monks, priests, and bishops came to Alaska to minister to the Russians and natives, traveling land and sea to bring the Gospel to the people. In the process, many saints were shown forth in the Americas, including protomartyr of All-America, St. Juvenaly of Iliamna, St. Herman of Alaska, St. Tikhon of Moscow, St. Innocent of Alaska and Moscow, and St. Peter the Aleut.

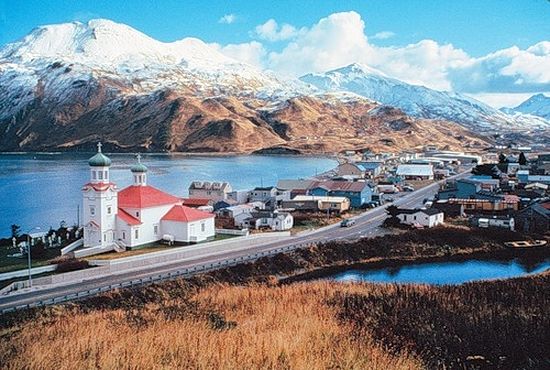

Today, there is a notable Alaskan expression of Orthodoxy that took root and grew over the last 200 years. It was the Orthodox who taught the natives how to read, and translated the Scriptures and services into the native languages. It was through this mission that Orthodoxy first came to America, and various historical situations and missionary endeavors led the Russian mission to expand to the United States and Canada.

Orthodox church in the village of Ninilchik (Alaska)

Orthodox church in the village of Ninilchik (Alaska)

The second wave of Orthodoxy coming to America was through immigration. Massive immigration of Arabs, Russians, Ukrainians, Romanians, Serbians, Albanians and others entered America through Ellis Island and other ports. Greeks especially came in several heavy waves of immigration—there’s a saying, wherever there is a seaport, there you will find Greeks!

Many times, the first things these immigrant groups did was form a “society of ________ (ethnicity)” and that society would rent or build a church, and try to get a pastor from their home country (who spoke their language) to come to America. There are many cases where multi-ethnic communities existed, and perhaps a Bulgarian priest might serve an Antiochian and Greek dominated parish, or something similar. It was an interesting and exciting time of new beginnings.

Indeed, Greek, Arab, and Slavic immigrants established the first congregation in the lower 48 states in New Orleans, Louisiana. Prior to their establishment as a congregation, they had a society that even raised up a militia to fight for the Confederate States in the American Civil War. This church—Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church—still exists, and has grown to be a large community today.

This period also saw the heirs of the Alaskan mission spread their reach to Canada and the lower 48 states. By 1900, the Holy Synod in Russia established the Diocese of the Aleutians and North America, with St. Tikhon of Moscow at the helm. St. Tikhon traveled from coast to coast tirelessly working to care for his growing flock, dedicating and consecrating churches for more recent Russian immigrants.

Soon, there were so many ethnicities represented in this country with largely disconnected and overlapping jurisdictions. Squabbles among the clergy, and trouble brewing back in the Old Countries—think Communism in Russia or Hitler’s invasion of Greece, for examples—led to increasing ethnic separations, or even splits within ethnic jurisdictions (the Russians, in particular, had a bitter split).

The third and fourth waves of Orthodox expansion in the Americas were by conversion. The third wave began when Fr. Alexis Toth, an Eastern Rite Roman Catholic priest, ran into conflict with the local Roman Catholic bishop who was trying to suppress Eastern Rite practices and other Roman Catholic ethnic groups. Livid from an unsatisfactory meeting with the local bishop, Fr. Alexis began to re-evaluate the nature of the Church and the claims of Rome, and eventually concluded that he needed to jump ship to the Orthodox Catholic Church.

In March 1892, he and 361 Eastern Rite Catholics were received into the Russian Orthodox Church. He began to evangelize other Eastern Rite Catholics, explaining why the Orthodox Church was the true ark of salvation. By the time of his death in 1909, approximately 20,000 so-called Uniates had come into the Russian Orthodox Church, and by 1916 an estimated 100,000 had entered. Many of these parishes are still operational today as Orthodox churches. We now honor Fr. Alexis as St. Alexis of Wilkes-Barre.

The fourth wave of growth has been slow and steady over the last generation. Evangelicals, Anglicans, Roman Catholics, and non-Christians alike are discovering the Orthodox Church, especially as many parishes have now embraced the English language, and the average parishioner has assimilated into the fabric of America (usually while holding onto his ethnic identity). People are discovering that this ancient, unchanged faith is surprisingly relevant to their lives today, and embracing it wholeheartedly.

One of the more interesting stories of this fourth wave was when 2,000 evangelicals came into the Antiochian Orthodox Archdiocese in 1987. The short of it is that a group of Campus Crusade for Christ ministers were seeking to be true to the ideals of the early Church in their ministries, and through investigation, over time, their ministries and faith began to resemble that of the early Church (and consequently, the Orthodox Church). Despite having doors slammed in their faces by several Orthodox hierarchs, they found a warm reception in the Antiochian Orthodox Archdiocese. They were received en masse, and since then have integrated nicely into this Arab-Syrian jurisdiction, bringing a new enthusiasm and refreshment into American Orthodoxy.

Skipping over a great deal of history and grossly oversimplifying, these four waves did not successfully create a single Orthodox administration in this country. As the churches here grew, new churches were established, and more cohesive structures connecting the various churches developed—usually along ethnic lines. This is why a phone book may have “Russian Orthodox,” “Greek Orthodox,” or “Albanian Orthodox” entries.

In 1970, many of the Russian churches (both from the original mission and from immigration) desired a uniquely American-run administration, independent of Russia. It was hoped that all of the other groups of Orthodox people would be excited about this idea of “The Orthodox Church in America” and all join together in a single infrastructure. A few Romanian, Bulgarian, and Albanian churches shared this idea, but many Orthodox in America were not thrilled with what is now known as the OCA. After squabbles in the 1920s and 1940s within the Russian churches, the creation of the OCA deepened the existing schism with the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia (ROCOR)—a schism that has since been healed, thank God. (There are a few intramural arguments about the timing and canonical propriety of Moscow creating the OCA, but that discussion is for another time and place.)

To this day, there is a multiplicity of “jurisdictions” in this country, with many overlaps and unfortunate situations out of line with canonical norms. Still, we remain a single Church, a genuine expression of the universal Body of Christ, united in our sacraments and faith, and guided by the one Holy Spirit.

Administrative unity is on the horizon now. Over the years, several groups have been established to work toward this end; most recently the Episcopal Assembly of Canonical Orthodox Bishops of North and Central America was established to determine the way forward, and bind our many people, ethnicities, and clergy together more tightly—and over time, to correct any canonical irregularities that may exist.

From: On Behalf of All