Orthodox spirituality differs distinctly from any other "spirituality" of an eastern or western type. There can be no confusion among the various spiritualities, because Orthodox spirituality is God-centered, whereas all others are man-centered.

The difference appears primarily in the doctrinal teaching. For this reason we put "Orthodox" before the word "Church" so as to distinguish it from any other religion. Certainly "Orthodox" must be linked with the term "Ecclesiastic," since Orthodoxy cannot exist outside of the Church; neither, of course, can the Church exist outside Orthodoxy.

The dogmas are the results of decisions made at the Ecumenical Councils on various matters of faith. Dogmas are referred to as such, because they draw the boundaries between truth and error, between sickness and health. Dogmas express the revealed truth. They formulate the life of the Church. Thus they are, on the one hand, the expression of Revelation and on the other act as "remedies" in order to lead us to communion with God; to our reason for being.

Dogmatic differences reflect corresponding differences in therapy. If a person does not follow the "right way" he cannot ever reach his destination. If he does not take the proper "remedies," he cannot ever acquire health; in other words, he will experience no therapeutic benefits. Again, if we compare Orthodox spirituality with other Christian traditions, the difference in approach and method of therapy is more evident.

A fundamental teaching of the Holy Fathers is that the Church is a "Hospital" which cures the wounded man. In many passages of Holy Scripture such language is used. One such passage is that of the parable of the Good Samaritan: "But a certain Samaritan, as he journeyed, came where he was. And when he saw him, he had compassion . So he went to him and bandaged his wounds, pouring on oil and wine; and he set him on his own animal, and brought him to an inn, and took care of him. On the next day, when he departed, he took out two denarii, and gave them to the innkeeper, and said to him, 'Take care of him; and whatever more you spend, when I come again, I will repay you" (Luke 10:33-35).

In this parable, the Samaritan represents Christ who cured the wounded man and led him to the Inn, that is to the "Hospital" which is the Church. It is evident here that Christ is presented as the Healer, the physician who cures man's maladies; and the Church as the true Hospital. It is very characteristic that Saint John Chrysostom, analysing this parable, presents these truths emphasised above.

Man's life "in Paradise" was reduced to a life governed by the devil and his wiles. "And fell among thieves," that is in the hands of the devil and of all the hostile powers. The wounds man suffered are the various sins, as the prophet David says: "my wounds grow foul and fester because of my foolishness" (Psalm 37). For "every sin causes a bruise and a wound." The Samaritan is Christ Himself who descended to earth from Heaven in order to cure the wounded man. He used oil and wine to "treat" the wounds; in other words, by "mingling His blood with the Holy Spirit, he brought man to life." According to another interpretation, oil corresponds to the comforting word and wine to the harsh word. Mingled together they have the power to unify the scattered mind. "He set him in His own beast," that is He assumed human flesh on "the shoulders" of His divinity and ascended incarnate to His Father in Heaven.

Then the Good Samaritan, i.e. Christ, took man to the grand, wondrous and spacious inn--to the Church. And He handed man over to the innkeeper, who is the Apostle Paul, and through the Apostle Paul to all bishops and priests, saying: "Take care of the Gentile people, whom I have handed over to you in the Church. They suffer illness wounded by sin, so cure them, using as remedies the words of the Prophets and the teaching of the Gospel; make them healthy through the admonitions and comforting word of the Old and New Testaments." Thus, according to Saint Chrysostom, Paul is he who maintains the Churches of God, "curing all people by his spiritual admonitions and offering to each one of them what they really need."

In the interpretation of this parable by Saint John Chrysostom, it is clearly shown that the Church is a Hospital which cures people wounded by sin; and the bishops and priests are the therapists of the people of God.

And this precisely is the work of Orthodox theology. When referring to Orthodox theology, we do not simply mean a history of theology. The latter is, of course, a part of this but not absolutely or exclusively. In Patristic tradition, theologians are the God-seers. Saint Gregory Palamas calls Barlaam [who attempted to bring Western scholastic theology into the Orthodox Church] a "theologian," but he clearly emphasises that intellectual theology differs greatly from the experience of the vision of God. According to Saint Gregory Palamas theologians are the God-seers; those who have followed the "method" of the Church and have attained to perfect faith, to the illumination of the nous and to divinisation (theosis). Theology is the fruit of man's cure and the path which leads to cure and the acquisition of the knowledge of God.

Western theology, however, has differentiated itself from Eastern Orthodox theology. Instead of being therapeutic, it is more intellectual and emotional in character. In the West [after the Carolingian "Renaissance"], scholastic theology evolved, which is antithetical to the Orthodox Tradition. Western theology is based on rational thought whereas Orthodoxy is hesychastic. Scholastic theology tried to understand logically the Revelation of God and conform to philosophical methodology. Characteristic of such an approach is the saying of Anselm [Archbishop of Canterbury from 1093-1109, one of the first after the Norman Conquest and destruction of the Old English Orthodox Church]: "I believe so as to understand." The Scholastics acknowledged God at the outset and then endeavoured to prove His existence by logical arguments and rational categories. In the Orthodox Church, as expressed by the Holy Fathers, faith is God revealing Himself to man. We accept faith by hearing it not so that we can understand it rationally, but so that we can cleanse our hearts, attain to faith by theoria[1] and experience the Revelation of God.

Scholastic theology reached its culminating point in the person of Thomas Aquinas, a saint in the Roman Catholic Church. He claimed that Christian truths are divided into natural and supernatural. Natural truths can be proven philosophically, like the truth of the Existence of God. Supernatural truths - such as the Triune God, the incarnation of the Logos, the resurrection of the bodies - cannot be proven philosophically, yet they cannot be disproven. Scholasticism linked theology very closely with philosophy, even more so with metaphysics. As a result, faith was altered and scholastic theology itself fell into complete disrepute when the "idol" of the West - metaphysics - collapsed. Scholasticism is held accountable for much of the tragic situation created in the West with respect to faith and faith issues.

The Holy Fathers teach that natural and metaphysical categories do not exist but speak rather of the created and uncreated. Never did the Holy Fathers accept Aristotle's metaphysics. However, it is not my intent to expound further on this. Theologians of the West during the Middle Ages considered scholastic theology to be a further development of the teaching of the Holy Fathers, and from this point on, there begins the teaching of the Franks that scholastic theology is superior to that of the Holy Fathers. Consequently, Scholastics, who are occupied with reason, consider themselves superior to the Holy Fathers of the Church. They also believe that human knowledge, an offspring of reason, is loftier than Revelation and experience.

It is within this context that the conflict between Saint Gregory Palamas and Barlaam should be viewed. Barlaam was essentially a scholastic theologian who attempted to pass on scholastic theology to the Orthodox East.

Barlaam's views - that we cannot really know Who the Holy Spirit is exactly (an outgrowth of which is agnosticism), that the ancient Greek philosophers are superior to the Prophets and the Apostles (since reason is above the vision of the Apostles), that the light of the Transfiguration is something which is created and can be undone, that the hesychastic way of life (i.e. the purification of the heart and the unceasing noetic prayer) is not essential - are views which express a scholastic and, subsequently, a secularised point of view of theology. Saint Gregory Palamas foresaw the danger that these views held for Orthodoxy and through the power and energy of the Most Holy Spirit and the experience which he himself had acquired as a successor to the Holy Fathers, he confronted this great danger and preserved unadulterated the Orthodox Faith and Tradition.

Having given a framework to the topic at hand, if Orthodox spirituality is examined in relationship to Roman Catholicism and Protestantism, the differences are immediately discovered.

Protestants do not have a "therapeutic treatment" tradition. They suppose that believing in God, intellectually, constitutes salvation. Yet salvation is not a matter of intellectual acceptance of truth; rather it is a person's transformation and divinisation by grace. This transformation is effected by the analogous "treatment" of one's personality, as shall be seen in the following chapters. In the Holy Scripture it appears that faith comes by hearing the Word and by experiencing "theoria" (the vision of God). We accept faith at first by hearing in order to be healed, and then we attain to faith by theoria, which saves man. Protestants, because they believe that the acceptance of the truths of faith, the theoretical acceptance of God's Revelation, i.e. faith by hearing saves man, do not have a "therapeutic tradition." It could be said that such a conception of salvation is very naive.

The Roman Catholics as well do not have the perfection of the therapeutic tradition which the Orthodox Church has. Their doctrine of the Filioque is a manifestation of the weakness in their theology to grasp the relationship existing between the person and society. They confuse the personal properties: the "unbegotten" of the Father, the "begotten" of the Son, and the procession of the Holy Spirit. The Father is the cause of the "generation" of the Son and the procession of the Holy Spirit.

The Latins' weakness to comprehend and failure to express the dogma of the Trinity shows the non-existence of empirical theology. The three disciples of Christ (Peter, James and John) beheld the glory of Christ on Mount Tabor; they heard at once the voice of the Father, "This is My beloved Son," and saw the coming of the Holy Spirit in a cloud, for, the cloud is the presence of the Holy Spirit, as Saint Gregory Palamas says. Thus the disciples of Christ acquired the knowledge of the Triune God in theoria (vision of God) and by revelation. It was revealed to them that God is one essence in three hypostases.

This is what Saint Symeon the New Theologian teaches. In his poems he proclaims over and over that, while beholding the uncreated Light, the deified man acquires the Revelation of God the Trinity. Being in "theoria" (vision of God), the saints do not confuse the hypostatic attributes. The fact that the Latin tradition came to the point of confusing these hypostatic attributes and teaching that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Son also, shows the non-existence of empirical theology for them. Latin tradition speaks also of created grace, a fact which suggests that there is no experience of the grace of God. For, when man obtains the experience of God, then he comes to understand well that this grace is uncreated. Without this experience there can be no genuine "therapeutic tradition."

And indeed we cannot find in all of Latin tradition, the equivalent to Orthodoxy's therapeutic method. The nous is not spoken of; neither is it distinguished from reason. The darkened nous is not treated as a malady, nor the illumination of the nous as therapy. Many greatly publicised Latin texts are sentimental and exhaust themselves in a barren ethicology. In the Orthodox Church, on the contrary, there is a great tradition concerning these issues, which shows that within it there exists the true therapeutic method.

A faith is a true faith inasmuch as it has therapeutic benefits. If it is able to cure, then it is a true faith. If it does not cure, it is not a true faith. The same thing can be said about medicine: a true scientist is the doctor who knows how to cure and his method has therapeutic benefits, whereas a charlatan is unable to cure. The same holds true where matters of the soul are concerned. The difference between Orthodoxy and the Latin tradition, as well as the Protestant confessions, is apparent primarily in the method of therapy. This difference is made manifest in the doctrines of each denomination. Dogmas are not philosophy, neither is theology the same as philoosphy.

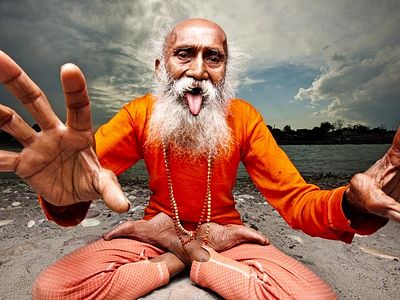

Since Orthodox spirituality differs distinctly from the "spiritualities" of other confessions, so much the more does it differ from the "spirituality" of eastern religions, which do not believe in the Theanthropic nature of Christ and the Holy Spirit. They are influenced by the philosophical dialectic, which has been surpassed by the Revelation of God. These traditions are unaware of the notion of personhood and thus the hypostatic principle. And love, as a fundamental teaching, is totally absent. One may find, of course, in these eastern religions an effort on the part of their followers to divest themselves of images and rational thoughts, but this is in fact a movement towards nothingness, to non-existence. There is no path leading their "disciples" to theosis-divinisation (see the note below) of the whole man.

This is why a vast and chaotic gap exists between Orthodox spirituality and the eastern religions, in spite of certain external similarities in terminology. For example, eastern religions may employ terms like ecstasy, dispassion, illumination, noetic energy, etc. but they are impregnated with a content different from corresponding terms in Orthodox spirituality.

From Chapter 2 of Orthodox Spirituality: A brief introduction, published in 1994 by Birth of the Theotokos Monastery, Levadia, Greece. See also "Way Apart: What is the Difference Between Orthodoxy and Western Confessions?", by Metropolitan Anthony (Khrapovitsky) of Kiev and Galic.