I have recently written about the archaeological discoveries of ancient Christian house churches in the middle east.

In that piece, I discussed how the manuscripts found at these sites shows us that a central practice within these early church communities was the sacrificial mystery of the holy Eucharist (along with baptism), and very much in a way that is consonant with later Eucharistic rites of the fourth century, as well as the rites described in the first-century Didache. I also alluded briefly to the iconographic frescoes in these churches (both at Megiddo and Dura Europos), but I’d like to dive into that aspect a little further.

Up until the late-19th century, it was a common polemic of Protestant apologists (against both Rome and the Orthodox Church) that the veneration given to saints was a late innovation and even degradation of the faith (perhaps as late as the fifth or sixth century). Not only this, but it was an established presumption that Judaism (in this case, Second Temple Judaism, as at the time of Christ and His apostles) was wholly iconoclastic, and that it would be impossible to imagine how the early Christians could have ever developed an iconographic tradition, as a result—given both their heritage and dependence upon the Judaism prior to Christianity.

However, there is now an abundance of evidence to the contrary, beyond the pale of the Orthodox-Catholic tradition.

From the standpoint of popular traditions, most are aware of the “Icon Made Without Hands” that the Lord imprinted into a cloth and gave to King Abgar of Edessa (reigned A.D. 13–50) of the Osroene Kingdom. There is also the tradition of Luke the Physician painting the first icon of the Theotokos (the Virgin Mary) and the infant Jesus (the Hodegetria, which is currently enshrined at a church on Mount Athos). Eusebius of Cæsarea even wrote about the existence of icons and statues of Christ, which had existed well before his time (A.D. 263-329): “Eusebius tells of a statue said to be that of Christ which existed in Palestine, and did not think it strange. He had heard too of portraits of Peter and Paul” (The Orthodox Liturgy, p. 23).

Speaking of the portraits of saints, Wybrew also notes:

It is quite probable that Christians began painting portraits of distinguished and venerated members of the Church very early on. The Apocryphal Acts of John tell of a portrait of the Apostle which one of his disciples, Lycomedes, commissioned from an artist friend. Lycomedes put it in his bedroom, and adorned it with flowers.

Besides basic portraiture, the funerary art tradition in the early Church is easily demonstrated in the Roman catacombs.

There is little doubt that Christians followed contemporary practice in having funerary portraits painted of distinguished church members . . . and perhaps as early as the third century, Christian images were venerated by being garlanded with flowers and having lights burnt in front of them.

But what about the supposed iconoclasm of Judaism? Wouldn’t this have prohibited the advent of both iconography and statuary among the early Christians?

On the contrary, and in agreement with the traditions of the Church, Judaism of this time was emphatically not iconoclastic, nor was Judaism itself ever really monolithic with respect to many key beliefs. Indeed, there have been some rather important archaeological discoveries in the past century or so that have debunked this position entirely.

If one is being honest about the witness of the holy scriptures, we must admit that there are several approving commandments related to the creation of iconography and even statuary in the old testament. Both the tabernacle and temple were adorned with a multitude of images, both two- and three-dimensional, which depicted everything from angels to pomegranates—the priest would prostrate himself before these images and statues, no less. The temple was filled with a glorious array of colors and images, with theological symbolism underlying it all. And with the incarnation of Jesus Christ, this more “symbolic” iconography transitioned to a more Christian or incarnational pattern (1 John 1:1–3), with the image of Christ, the saints, and his holy Mother.

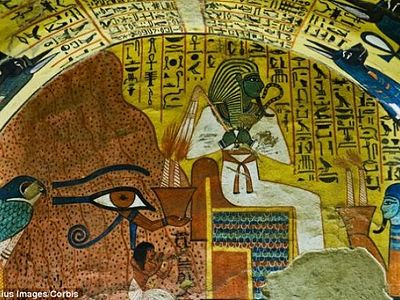

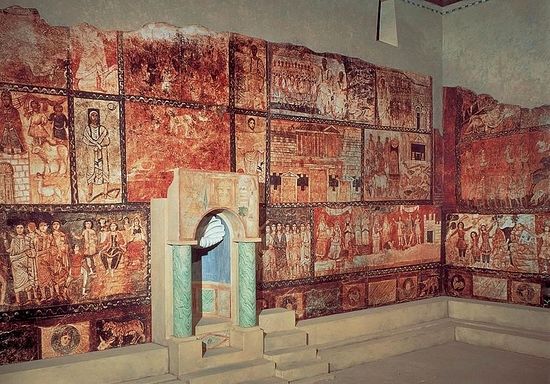

The village of Dura Europos was destroyed in 256. Thankfully, we have a glimpse into their world through the discovery of these relatively well-preserved archaeological digs. These sites drew fervent interest in 1921, when a number of religious frescoes were uncovered:

The archaeologist discovered that three of the covered homes had been renovated for use as religious buildings. One had become a Mithraeum, dedicated to the worship of the god Mithras. Another had undergone structural modifications to become a Jewish synagogue. The third home had been converted to a Christian church. This Christian church is especially important as it is the earliest complete church extant.

Note that last statement. At the time of its discovery, this was the earliest extant Christian Church preserved to the present day. This goes beyond mere speculation as to what the “early church” was like, but is the early church itself staring back at us from across the centuries.

The arrangement of the church at Dura Europos reflects the well-established liturgical practices of the Christians, with a place for a Baptistry, an altar table for the bishop to oversee the celebration of the Eucharistic feast, and—last but not least—iconography. This discovery is, again, in harmony with the tradition of the Orthodox-Catholic Church. However, for those who look upon the tradition of the Church with any amount of skepticism or disdain, the existence of such archaeological evidence should be, at the very least, intriguing.

As the Church was given freer jurisdiction by the Emperor St. Constantine the Great in the fourth century, the larger temples and churches of the Roman Empire had a similar arrangement, architecturally-speaking, to these house churches, but on a much grander scale (i.e. the basilica):

An examination of the remains yields much about the liturgy of the early Christian church.

A typical Roman upper class house was centered around a columned courtyard with an open room caled the atrium. In the center of the courtyard was a pool or impluvium. At the opposite end from the entrance was a raised area tablinum containing a table and used by the family as a reception area and for ceremonial functions.

In the Dura Europos home converted to a church, scholars speculate that the congregation gathered around the pool, which was used for baptism. In the tablinum sat the bishop, who presided over the Eucharist, celebrated at the table. This arrangement provides a logical basis for the liturgical arrangement of later basilica churches.

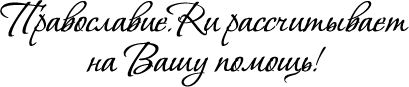

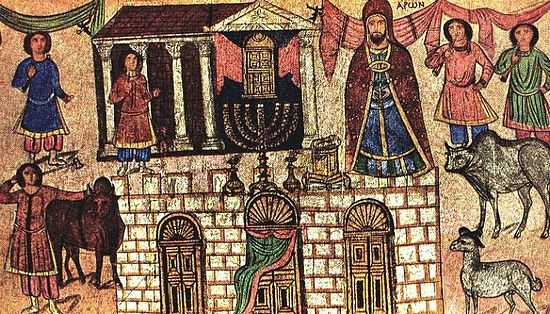

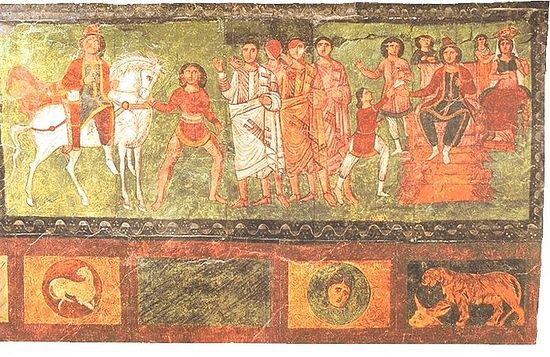

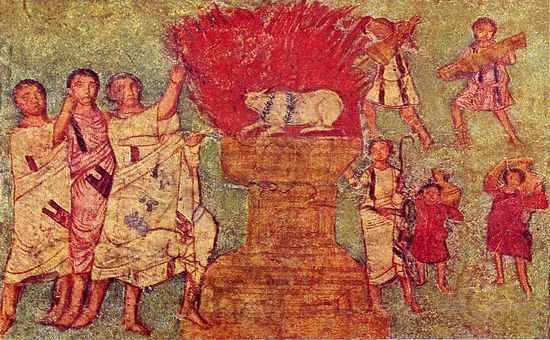

As mentioned earlier, there were iconographic depictions discovered in both the Jewish synagogue and the Christian house church at Dura Europos. Below are a few pictures from the Jewish synagogue, showing frescoes which display Old Testament imagery, including a scene from the book of Esther, the golden calf “incident,” and the patriarch Abraham himself:

In the church at Dura Europos, there are many iconographic frescoes as well.

The first is a scene from the Holy Gospels where Jesus heals a paralytic man. The depiction shows Jesus standing over the paralytic telling him, “That you may know that the Son of Man has power to forgive sins: rise up, take up your bed and walk.” Interestingly enough, this image is above the baptistry, showing a connection between baptism and being healed from the corruption of death. You can clearly see next to the scene the paralytic taking his cot and walking away like normal, just as in the gospel story (and much like the later icons of this Gospel story):

Dura Europos Church

Dura Europos Church

Next to this, there is a scene of the Lord Jesus extending His hand out towards the apostle Peter, in order to avoid drowning in the water (also from the gospels):

The continuity between the the worship of late Judaism and that of early Christianity seems apparent here, not only from the perspective of the prayers of thanksgiving within the Eucharistic context (as discussed in the previous article), but also with this common practice of both catechetical and decorative iconography.

Orthodox worship and devotional piety is best understood when it is approached from the standpoint of Christened temple (and synagogal) worship. Christ did not come to abolish the law and the prophets, but to fulfill them, and it is in him that we understand the fulfilled worship of Orthodox Christianity—an icon of the heavenly worship. This we see in the Epistle to the Hebrews as well as the Apocalypse. If one is looking to worship in the New Testament church, to assemble as the early believers did in these ancient house churches, then there is no better place to do so—joining in with the eternal worship of the one Church of Christ—than in the Orthodox Church.

Source: On Behalf of All