In Serbia the Theophany is also beloved feast day. As in other Orthodox countries, Southern Slavs have their own traditions that may seem extraordinary to those in northern climes.

The festal doxology has not ceased to resound beneath the domes of the St. Alexander Nevsky Church when out on the streets people are already preparing for the Great Blessing of the Waters. The cross is immersed thrice. Using a brush made of dried grasses the clergy sprinkles the assembly as they crowd around the holy water—the peace-loving Serbs have a culture that sets them apart from Western Europeans, and they show an impatience more resembling the Russians’—all push their way to the water that has such special qualities, and draw from it…

Every year on January 19, a multitude of people from all over Belgrade participate in the festivities, which are the central events in the Serbian capital on that day.

In the churchyard, the final preparations are ending. The clergy with the bishop at the fore lead the procession. The young men impatiently rattle their chain mail and armor like that worn by Serbian warriors of a bygone age. They look quite natural in this church dedicated to the memory of the Russian soldiers who defended their Serbian brothers in the war against the Turks, 1877–1878.

Just one more moment, and all this magnificent, multitudinous procession will move with crosses and banners toward St. Sava Lake—the site where the people’s festival culminates. Little bells ring tenderly in the hands of a young acolyte at the head of the procession; the military step forward in measures paces, carefully bearing the wooden crucifix; the Serbian banners flutter loudly in the wind.

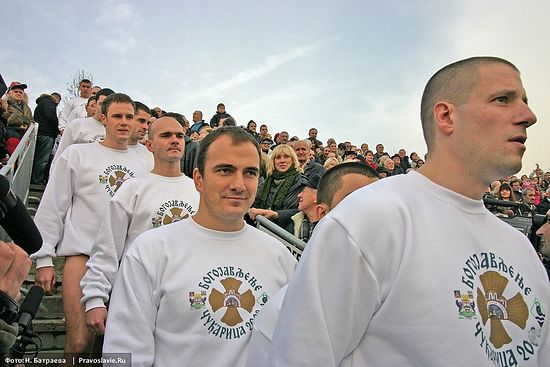

At the sight of the crosses and banners, joyful shouts carry from the risers filled with people. The bishop and clergy, the mayor and governmental representatives, the military and the police occupy the places of honor. Three soldiers marking their steps triumphantly carry the cross made from frozen last year’s holy water and decorated with tri-colored ribbons and flowers. This will be the main reward to the strongest, whose name we will learn in just a few minutes.

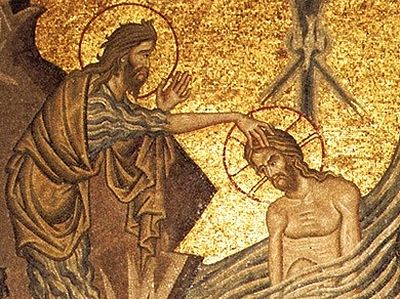

On the day of the Theophany, after the Divine Liturgy and the rite of the water blessing, in certain cities and villages of Serbia a cross is cast into a body of water and swimmers race to fetch it. According to tradition, it is thrown by a priest or bishop. This custom is also practiced in other Balkan countries: Greece, Macedonia, Montenegro, and Bulgaria. The meaning of this competition is symbolic. Before swimming the participants are sprinkled with holy water, and the winner is given a metal or wooden crucifix.

The competitors wear white clothing with “Theophany” written on them. The swimmers—all fine young Serbs—are preparing themselves for the swim: they must cover a thirty-three meter distance in ice-cold water. The muscular ranks are frozen in expectation of the start. The bishop casts the cross into the water—the first to reach it will be the hero of the day. The signal is given, and the water’s surface breaks in one explosion as the swimmers all dive into it together. The water is roiling from the intense movement of arms and legs. Multi-colored rings undulate away from the daring fellows—many of them have covered themselves with oil in order to shield themselves from the cold.

A triumphant call carries through the risers—the winner, still in the water, raises the frozen cross over his head.

They say that the tradition of everyone immersing themselves into the water on Theophany is forgotten in Serbia. Only rarely will someone enter the water in a place where no one can see him, cross himself and saying the prayer, “In the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit,” immersing himself three times in the icy water…

The celebrations culminate with the boisterous congratulations of the recent competitors. The bishop hands the winner a metal crucifix, while the icy one gradually melts, blessing with its own melted water the waters of St. Sava Lake.

Christ is appeared,” Belgrade pronounces the traditional Serbian greeting, and it echoes throughout the country. “Truly He is appeared,” answers the Serbian land of Kosovo and Metochia, where at this same time unhurried prayer pours out behind the high walls of the monastery, and the Great Blessing of the Waters in served. There are no large cross processions here, no swimming for the cross or rewards to the winner—the new Hagarenes who have taken over this cradle of Serbianism dictate their own laws.

The courtyard is deserted in the monastery of the Patriarchate of Pec—the child of St. Sava and throne of the Patriarch of Serbia. Several people have arrived from the nearby villages, and from central Serbia as well. Shivering from the bone-chilling wind that rips from the ravine, nuns sing the festal hymns and the troparion to the Theophany. The water is blessed. The priest sprinkles the smiling people—the beloved, faithful children of the much-suffering Serbian nation…