In the winter of 1937, the sound of gunfire could be heard throughout the territory of the Soviet Union… The clergy, who accepted their priestly rank along with a crown of martyrdom, lay in the ditches of common graves, and died from sickness and hunger behind camp gates and in prison walls. What motivated them to take that step?

How could a nation that stood guard for centuries over the Orthodox faith so cruelly and cynically trample its own sanctity into the ground? And what impression upon the Orthodox world did December 1937 make?

Igumen Valerian (Golovenko), a military historian and the rector of the Church of the New Martyrs and Confessors of Russia at the Lukianov cemetery in Kiev answers these and other questions.

“The mass destruction by the Bolsheviks of the clergy provoked an entirely unexpected reaction among the clergy…

—Fr. Valerian, tell us, how were the inhabitants of a state that was for centuries a stronghold of Orthodoxy capable of destroying their holy shrines and pastors?

—The problem is that during the period of the October revolution, an ideology formed that had no place for the Orthodox faith. Moreover Orthodoxy, which was very clearly associated with the former sovereignty, still remained the religion of the overwhelming majority of citizens in the former Russian Empire, or at least in its European portion.

Of course, levels of Christianization varied from person to person, depending upon his or her social origins. There were religious peasants, formally Christianized intelligentsia, and, already at that time, a partially de-Christianized proletariat, which became the backbone of the revolutionary forces.

But despite all this, mass persecutions against Christians had not yet happened. There were isolated cases, like for example the murder of Holy Hieromartyr Vladimir (Bogoyavlensky) in 1918.

—That is, mass repressions began much later?

—Yes. In the 1920s, the civil war ended. The White Army was crushed, and only the last few strongholds of resistance remained to be quelled—such as the White Guard partisan battalions in Transcaucasia or the Cossacks of Holodny Yar. It was just a matter of time.

The new regime, fearless of popular outrage, started their wholesale uprooting of the Church from the new, atheistic society, paying no attention to how people would react. Moreover the accusations against the clergy were, as a rule, purely formalities:

“You, comrade pope [derisive word for priest.—Trans.] refused to give medical care to Red Army soldiers?”

“I took care of everyone…”

“Aha! That means you took care of White Army soldiers also!”

But the mass destruction of the clergy, contrary to the Bolsheviks’ predictions, provoked a completely unpredictable reaction. Not only monastics, but even some widowed priests who received the monastic tonsure occupied the places of the destroyed episcopate.

These people always inspired in me enormous respect. After all, they took these higher ecclesiastical positions not for the sake of honor or gain, but with full understanding that in the very near future they could expect the camp’s barbed wire or the execution ditch. In them was the spirit of the early Christians—the readiness for martyrdom in the name of their faith.

What was the signal for the beginning of the “Red Terror”?

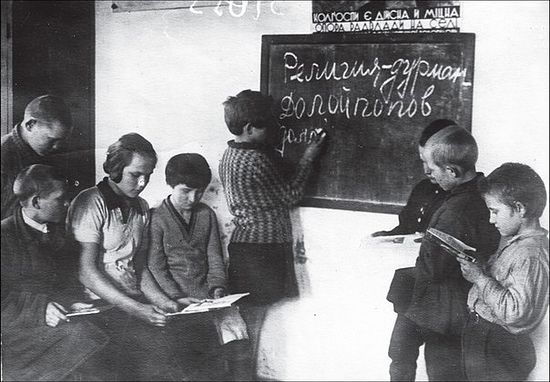

“Pioneers, sound the alarm—your parents are praying to God!”

“Pioneers, sound the alarm—your parents are praying to God!”

—That means that the starting point of full-scale persecutions against the Church was the 1920s?

—No, it happened much later. If you recall the 1920s, you will not see obvious mass repressions against the Church clergy. Let’s take a look—what served as the signal for the beginning of the “Red Terror”?

The fact is that in 1935, a population census was taken. A document was placed on Stalin’s desk that spoke eloquently that the majority of the people in the “nation of atheists” still consider themselves believing Christians.

The reaction was not long to come. The leader issued a secret directive with a clear message: to destroy a specific number of clergymen.

—And what about the ordinary people? Did they only destroy the clergy during the “Church” repressions?

—Of course not. After all, even in the early stages of the Soviet Nation’s existence it became obvious that Trotsky’s idea of “exporting” the revolution to the West looked good on paper, but did not correspond to reality.

The Poles decidedly dispelled the illusion held by the builders of communism. After defeating the Red Army of Tukhachev near Warsaw, they gave them to understand that the “comrades” would have to build communism in only one country. The first step in this construction work was the liquidation of zealots—the so-called “professional revolutionaries”.

The people who destroyed the imperial regime had fulfilled their function, and there was no longer any need for them. It became disadvantageous and even dangerous to keep them around—in the end, a true revolutionary will always be dissatisfied with everything. Therefore, as soon as the final shots were fired on the battlefields of the Civil War, those who had only recently been killing White Army officers and the nobility and defiling churches, now found themselves against the wall.

The most curious thing is that the most widespread accusation in those years (although the Bolsheviks usually acted according to the principal of “Give us the person, and we’ll find the article”) was “participation in a counter-revolutionary group of Tikhonite-Church people”. No one bothered with any facts. Why you need facts if there is an order?

“The soviets chose to persecute in December for practical reasons.”

—But why December? After all, the persecutions went on for more than one year…

—As cynical as it may sound, the soviets chose December for practical reasons. The earth was not yet fully frozen, and so it was easier to dig ditches. But it was already cold enough for the corpses to freeze; the characteristic smell would not be so strong, and not attract extra attention.

In a word, the production culture was lifted. In those years, only fourteen working churches remained in Kiev and Kiev Province. This was total destruction.

—When exactly was Stalin’s order brought to fulfillment?

—The ditch on the far lot of the Lukianov cemetery in Kiev was filled from August 1937 to February 1938.

It was in 1937 that the so-called investigation began—in fact, this “investigation was really the spilling out of evidence and false confessions by which they tried to give it an appearance of legitimacy.

—How were priests usually arrested?

—The majority of arrests were conducted not in the church, but in the home, in order not to arouse the population’s ire. Men in leather jackets, with tablets fastened to their belts and accompanied by Red Army soldiers, would knock at the door of the house at night, and if the priest did not open the door himself, they would break it down themselves with their rifle butts, bust in and take the clergyman “until things are explained”.

In isolated cases they might allow him to take a small bundle of belongings, but as a rule all understood perfectly that he would not need it. Rarely the arrested would sit in a cell for a week; as a rule, he would receive a bullet in the back of his head on the next day, and sometimes as soon as he arrived at the prison.

A lock would be hung on the door of the parish church, and they would wait until people would stop coming to the church at their customary time. Then they would pillage the church.

—How advantageous was it to rob the churches? Supporter sof the soviet regime still talk about huge sums of money expropriated from the Church…

—Here we have to say that the scale of things robbed was directly proportionate to the cunning of the robbers.

Sacred vessels and icon covers can be guilded with silver and gold. In very rare cases, they are made of silver, but not of the highest quality. Therefore, the real value was in the old icons, and if one of the robbers knew someone knowledgeable about antiques, then the ancient icons would end up in personal collections, and bring the robbers genuinely large sums.

But in general, church sacred objects usually have more spiritual than material value, and therefore, contrary to the widespread stereotype, they were not a serious source of profit.

The businesses and apartments of the “bourgeoisie” were much more interesting to rob. The robbing of churches bore a more ritual than practical character.

Chopped up icons, altars filled with refuse, murdered priests, and empty churches were supposed to visually demonstrate to people that there is no God.

—Where else was this ritual character also manifested, and what rituals are we speaking about in particular?

—It is sufficient to recall the Bolsheviks’ outward appearance. “The class strugglers” rejected all the esthetics of the Tsarist uniform with its epaulets and white gloves, and changed to a strange sort of uniform that reminds one of an old Russian caftan, and a “budyenovka” cap that looked like a medieval Russian war helmet, but with an element of buffoonery.

In general any esthetics were considered a holdover from the bourgeoisie, and that meant they needed to be destroyed. The soldier of the new country had no right to look good, he should be like everyone else. The simple folk called these soldiers “the horned ones”, or “the one-horned devils”. This was not only due to the hat’s peculiar form but also because of the symbol on it: a red star.

Even at the end of the nineteenth century, many ecclesiastical and societal figures said plainly that the communists use a satanic symbol—the pentagram. It was precisely then that not only in Russia, but all over Europe, there was a real explosion of occult teachings of all kinds, which had an influence on the nascent bolshevism.

—But why did the Bolsheviks declare war on esthetics?

—Let’s recall the history of revolutionary art. We can see that at that very time, a tendency came into being of calling a certain performance “art”. Like this, for example: “Let’s urinate on an acclaimed masterpiece and then all laugh at it.” It was precisely in the revolutionary period that anti-esthetic values began to form.

It was at the beginning of the twentieth century that we see the rise of innovators in art—the cubists, abstractionists, and so on. Where did they come from?

The thing is that every person has his own idea of esthetics—something he took in with his mother’s milk. Ancient Russian wood-carving, Ukrainian ornamentation, Gothic architecture…

But don’t forget that some people due to their background never developed any taste in visual arts, especially religious art. That is why their only way out was to present buffoonery and mockery of generally accepted esthetical canons as a fashionable alternative—one that was in fact nothing more than talentless brushstrokes and ugliness.

“It wasn’t the Chinese or the Latvians who robbed and defiled our churches. They were the Mishkas and Grishkas, who their mothers took to church in the morning…”

—But just the same, why did people so quickly deny the values that they had taken in with their mother’s milk?

—Let’s begin with the fact that industry had been transferred to a capitalist basis, and the Church occupied a much smaller place in the lives of the proletariat—the factory workers. The worker labors all day at the bench, and in his spare time he prefers to relax in the pub, rather than take his family to church.

Besides this, the factory owners—and these were mostly Germans and Jews—were foreign to Orthodox feast days, and therefore more inclined to give the workers an extra day off on the weekend than to let them go to church on weekdays.

Thus, in the prerevolutionary period, a strata of un-christianized society had already been formed—the proletariat. But what had to be done with people so that those who yesterday considered themselves Christians, today are demolishing everything that was sacred to them? After all, it wasn’t the Jews, Chinese, and Latvians who robbed and defiled our churches. This was done by the Mishkas and Grishkas whose mothers used to take them to church in the morning.

This was a formality. It was a formality that the city dwellers started taking for faith, and which they were rid of when offered a red flag as an alternative. That is how the new man was formed— “homo soveticus”.

“Parents, don’t throw us off course, don’t do Christmas and Christmas trees.” “Bring up your children with pedagogues, and not with God.”

“Parents, don’t throw us off course, don’t do Christmas and Christmas trees.” “Bring up your children with pedagogues, and not with God.”

—Do you agree that communism is more a religion than an ideology?

—Communism has all the features of a neo-religion,

with all its lameness. It is when many things are accepted

as faith that in and of themselves are unconvincing,

absurd and paradoxical.

In the first stages of a person’s consciousness, his

moral foundations were shaken by the rejection of all

morality. We only have to recall the “theory of a

glass of water,” conceived by Alexandra Kolontai.

According to her, it is the same for a Komsomol girl to

have sex as it is for her to drink a glass of water.

But then, the soviet leaders worked out the “Moral codex of builders of communism”. Because it is not so easy to govern an immoral person, the leaders of the proletariat were forced to return those same Christian morals to society, only not on a religious, but ideological basis. After all, soviet society was post-Christian.

“The New Martyrs showed us an example of what one who calls himself a pastor must remember: “The good pastor lays down his life for his sheep.”

—What do you think—is this spiritual terror connected with the beginning of the Great Patriotic War, which broke out on the territory of the USSR four year later?

—All coincidences are objective laws that we don’t understand. Why did World War II break out two years after the end of these repressions against the Church, and in another two years, the Great Patriotic War [against the Soviet Union.—Trans.]?

It is because when people depart from God, He finds a way to bring them back. It was not God Who turned away from us when we defiled our own churches and shot our priests. It was we who turned away from God.

Stalin returned the Church to the USSR not simply because the institute of political ideology wasn’t able to give the soldiers the spiritual support that the priests could, but because a soldier with God in his heart will fight better, knowing that another life awaits him after physical death.

Of course, there was another aspect to this—the Germans were reopening churches in occupied territories, which greatly inclined the local population to them, and Stalin simply couldn’t help but do the same, in order to sweeten the pill for the people.

Now some citizens who consider themselves great patriots are inclined to think that “Koba” [what Stalin called himself] was almost a saintly protector of the faith in all the USSR. This assertion has, to put it mildly, very little to do with reality. But that movement of his had key importance for both the soviet people, and for the breaking point in the war.

—What conclusions can we draw by remembering the New Martyrs?

—Even with such a massive, planned, totalitarian destruction of the clergy, the Church remained alive, passing honorably through the years of war and terror. This is that very example that the priests who fell into the execution ditches had read about as young seminarians.

It is an example of that fact that the Church is founded on the blood of martyrs. It shows that when you call yourself a pastor, you have to remember: “The good shepherd lays down his soul for his sheep.”

Are we worthy of their memory? Will we go all the way for those values that we preach? Do we live with Christ, and will we die with Christ? Everyone must ask himself these questions.

Remember, that honoring the memory of the New Martyrs does not mean just lighting a candle in church. Honoring them means being worthy of their memory.