If we see the Church year as a recapitulation or commemoration of the life of Christ, then the season of Lent, Holy Week, and the festival of Pascha is analogous to the temptation (and fasting) of the Lord in the wilderness, his suffering and defeat of death on the Cross, and his triumphal resurrection from the dead.

By pondering our participation in Christ’s life throughout the year—and especially through the season of Great Lent—we can better understand its purpose.

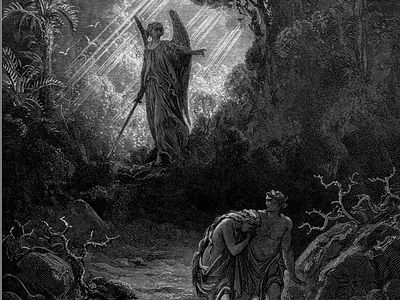

We enter into the Lenten season as people estranged from God, striving forward in hope of the resurrection. We are faced with a number of temptations, but the ability to overcome is given to us through Christ himself. This is supported by our increased partaking of the Eucharist during Lent with the Presanctified Liturgy. The icon of the resurrection shows the full glory of this reality, as we see Adam and Eve—the very personifications of sinful mankind—being pulled from the depths of hades by the hands of Christ, who has triumphed over both death and its author, the devil.

As we seek to image Christ more fully in our lives through the Lenten season, our focus is turned not inwardly towards ourselves, but rather outwardly towards others. Our fasting, almsgiving, and prayer is all purposed away from ourselves and our own concerns, and towards that of our neighbors, friends, and family.

All true asceticism is self-less. It is self-death for the sake and life of the world.

The heart of our journey towards both salvation and resurrection in Jesus Christ is found not in an intellectual fixation on our standing before God in eternity, an obsession over whether we can know “for certain” that we are “saved,” a right understanding of particulars of doctrine, or even a perfect explanation of the holy scriptures. The gateway to a resurrection unto life and a triumph over corruption is found chiefly in the mystery of forgiveness.

The Gospel for the appropriately named Forgiveness Sunday (the last Sunday before the beginning of Great Lent) explains:

If you forgive men their trespasses, your heavenly Father also will forgive you; but if you do not forgive men their trespasses, neither will your Father forgive your trespasses.

Many do not believe the scriptures at this point, or find this hard to fathom. We look for salvation or forgiveness in every other place but the forgiveness of others. Instead of looking to the promises of Christ in the Gospel, we twist the words of Paul to our own harm (2 Pet. 3:16), or use words from the old testament to contradict the new. As Orthodox Christians, there is no scripture more important to us and our spiritual growth than the Holy Gospels. And here, we learn everything necessary for the hope of salvation: forgiveness.

The concern here is not merely how we can be forgiven, but rather how we must be willing to forgive everyone else in order to have any hope of our own. The effectiveness of the Gospel apparently hinges on our willingness to be ever-forgiving of others. Instead of placing our hope in abstract and unknowable decrees, or a right understanding of certain aspects of Christian doctrine, our hope should be placed in how we receive the forgiveness of Christ, and our sharing of that mystery with others.

A person can have a perfect understanding of dogma, the canons of the Church, the ancient languages of the holy scriptures, and the finer points of Ancient Near Eastern history, but if that person has not love—if they lack forgiveness for others, and for every offense—then such a person is estranged from both love and the God of love.

If we have faith that is alone, rather than a faith “working through love,” such a faith can never save us (Jas. 2:19-20). Right belief about God makes us equal to the demons. But mercy, forgiveness, and love make us like God.

Salvation is not a matter of acquiring correct knowledge; it is acquisition of the Holy Spirit. And if we have acquired the Spirit of God, then we will reflect the love of the Holy Spirit in our willingness to both forgive and be forgiven.