Are all religious depictions idolatry? This is a question that plagued the Roman Empire near the end of the eighth century, and again in the ninth.

And though our patristic forebears no doubt assumed this aversion to iconography was settled once and for all—as celebrated most pointedly on the Sunday of Orthodoxy near the beginning of Great Lent—the aniconic spirit reared its ugly head again in the Protestant Reformation.

In my first article on this topic, I briefly examined the rhetoric of the Reformation and how this rhetorical style was used to influence the commoners on the subject of spiritual artwork: relics, icons, crucifixes, illuminated Gospel books, and so on. And while not all Reformers have the same position on this question, those who adopt the neo-iconoclastic notions of heretics past are most dependent on the arguments set forth by John Calvin.

For Calvin, not only was the veneration of icons and other religious relics forbidden, but also their very existence and placement in the homes and churches of faithful Christians. His arguments rest upon two basic assumptions: 1. All images of God/gods are idols, and 2. Christian images are therefore indistinguishable from pagan idols.

Let’s take a closer look.

All Images of God are Idols

As mentioned in the first post, the eleventh chapter of the first book of Institutes is where Calvin directly addresses the subject of religious imagery.

He begins his discussion by explaining how the scriptures distinguish “the true God from the false” by contrasting him with “idols” (1.11.1). From this point of view, even images or statues meant to represent the one true God are idols, for they erect something other than God for mankind to direct their worship:

God’s glory is corrupted by an impious falsehood whenever any form is attached to him. Therefore in the law, after having claimed for himself alone the glory of deity, when he would teach what worship he approves or repudiates, God soon adds, “You shall not make for yourself a graven image, nor any likeness.” By these words he restrains our waywardness from trying to represent him by any visible image, and briefly enumerates all those forms by which superstition long ago began to turn his truth into falsehood. (1.11.1)

And further:

[W]ithout exception he repudiates all likenesses, pictures, and other signs by which the superstitious have thought he will be near them. (1.11.1)

Beyond mere representations themselves, Calvin makes it plain that to venerate or worship such objects is both superstitious and forbidden by scripture:

[W]hen you prostrate yourself in veneration, representing to yourself in an image either a god or a creature, you are already ensnared in some superstition. For this reason, the Lord forbade not only the erection of statues constructed to represent himself but also the consecration of any inscriptions and stones that would invite adoration. (1.11.9)

And again:

Why do they prostrate themselves before these things? Why do they, when about to pray, turn to them as if to God’s ears? Indeed, what Augustine says is true, that no one thus gazing upon an image prays or worships without being so affected that he thinks he is heard by it, or hopes that whatever he desires will be bestowed upon him. (1.11.10)

To summarize, Calvin argues that to depict God in any way (to give him a “form”) is to detract from God’s glory. By creating an intermediary, we replace God and his own glory with a superstitious falsehood—an idol or false god, as idolatry especially in the Old Testament is often connected with the idea of a fake or nonexistent deity, as opposed to the true God of Israel. By offering veneration to these idols, Christians are no different than the Israelites paying homage to a golden calf, which itself was meant to represent Yahweh.

The Orthodox Response

In response to these initial claims, Orthodox Christians have much to say.

The scriptures tell us that Jesus Christ is the image or “form” of God (εἰκὼν τοῦ θεοῦ): “He is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation” (Col. 1:15). While the Father and Spirit are both formless and invisible (1 Tim. 1:17; Heb. 11:27; 1 John 4:20), the ὑπόστασις or person of the Son is revealed to us in the God-Man Jesus Christ: “No one has ever seen God; the only Son, who is in the bosom of the Father, he has made him known” (John 1:18).

God “became flesh and dwelt among us” (John 1:14), as the prophetic Emmanuel indicates (Matt. 1:23). When we look at Christ, we see the Father, and Jesus Christ is the “exact counterpart of [the Father’s] person” (Heb. 1:3). This word translated by the EOB as “counterpart” is χαρακτὴρ, implying something like an image stamped into a wax seal. Through the Incarnation, God made himself known to us as a circumscribed, touchable, breathing person—a person that was born, grew old, ate and drank, suffered, was buried, and resurrected after three days.

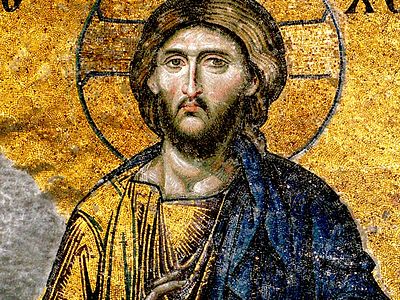

So when Calvin and his followers claim that depicting God in any way detracts from his glory, we must only point to Christ, for it is in the person of Jesus Christ (most importantly, at least) that we see the face of God. When we praise, worship, and magnify Jesus Christ, we are offering praise, worship, and honor to the all-holy Trinity: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Similarly, when we pay honor to the image of the Son of God in icons, we are paying honor to the prototype—to Jesus Christ himself. And when we honor the Saints, we are honoring the God whose uncreated light shines through their halos. The uncreated light of the shimmering gold leaf as it reflects the light of our oil lamps and candles—symbolic of the faithfulness of God shining forth in their saintly and Christ-like lives (which is, incidentally, why Orthodox Christians pay such close attention to the lives of the Saints).

Calvin’s arguments on this point seemingly presuppose that the Incarnation never happened; that the dispensation of the new covenant has yet to take place, and that there has been no Emmanuel or “God with us,” a God we can hear, see with our own eyes, and touch (1 John 1:1). These sorts of arguments are fitting for a religion such as Islam, but they are not theChristian Gospel; the Gospel of God made flesh, dwelling among us for our salvation.

Also missing from this presentation is any mention of the times when God commands his people to relate to him through an intermediary such as the bronze serpent, a relic that even miraculously healed people of their infirmities (Num. 21:9).

The flaw in Calvin’s viewpoint rests not only in Christology, but also in anthropology (as the two are inextricably linked). Mankind is created “according to the image of God,” as in the Greek translation of Genesis—κατʼ εἰκόνα θεοῦ (Gen. 1:27). And that image of God is Christ. Being created in the image of Christ, human beings are oriented towards a teleological purpose of transformation according to God’s likeness in him. This is our destiny, and why we are created: To become like Christ; to become like God. To be anything less is to be less than fully human, as Christ is the true and final Adam (1 Cor. 15:45).

Christian Artwork is Idolatry

The second tenet of Calvin’s argument revolves around the idea that not only are all religous images idolatrous (and perhaps even all images, though this is less clear), but also that Christian artwork in particular is idolatrous. In other words, images of Christ, the ever-virgin Mary, angels, and the Saints are all idols, regardless of who or what they depict.

For example, speaking of the Psalmist and his adversion to pagan idols, Calvin asserts:

[David] concludes in general that nothing is less commendable than for gods to be fashioned from any dead matter. [Ps. 135:15; cf. Ps. 115:4] (1.11.4)

This implies that attempts to fashion a form (eidos) of God is prohibited, at least as Calvin sees it. The problem being that, in David’s context, the idols are forms or images of false or non-existent deities. They are images of demons, even, as taught elsewhere. The Old Testament in particular is no stranger when it comes to associating idols (eidolon) with pagan gods (e.g. Gen. 31:19,34ff; Ex. 20:4; Num. 33:52; Dt. 5:8; 1 Sam. 31:9; 1 Ch. 10:9; 2 Ch. 14:5; 23:17; 24:18; 33:22; 34:7; Ps. 115:4; 135:15; Is. 10:11; 30:22; 48:5 (עֹצֶב); Hos. 4:17; 8:4; 13:2; 14:9; Mal. 1:7; Zech. 13:2), while in much of classical Greek literature, the ειδωλον are mere copies, rarely viewed as deities in-and-of-themselves. (Ανδριας and εικων are more frequently used in reference to images or statues of human beings.)

Looking at this from another angle, attempts to depict deity or the divine nature itself arescandalous, and should be avoided (Acts 17:29).

For example, in the written works of St. John of Damascus alone—the father of Orthodox iconology—we find:

If we attempt to make an image of the invisible God, this would be sinful indeed. It is impossible to portray one who is without body: invisible, uncircumscribed, and without form …

If anyone should dare to make an image of the immaterial, bodiless, invisible, formless, and colorless Godhead, we reject it as a falsehood …

I do not draw an image of the immortal Godhead, but I paint the image of God who became visible in the flesh, for if it is impossible to make a representation of a spirit, how much more impossible is it to depict the God who gives life to the spirit?

Continuing along the lines of images as “superstitious,” Calvin states:

Now we ought to bear in mind that Scripture repeatedly describes superstitions in this language: they are the “works of men’s hands,” which lack God’s authority [Isa. 2:8; 31:7; 37:19; Hos. 14:3; Micah 5:13]; this is done to establish the fact that all the cults men devise of themselves are detestable. (1.11.4)

Again, the context is pagan idolatry and the worship of false (non-existent) deities. In the Christian and especially Orthodox Christian context, icons are strictly fashioned anagogically according to the Gospel. They depict eternal truths and transcendent realities, revealing the deeper meaning of the world around us for our crippled senses.

Next, Calvin touches on the idea that veneration or honoring images—even Christian images—diminishes the glory due to God alone. This, he argues, is in fact a form of idolatry:

Men are so stupid that they fasten God wherever they fashion him; and hence they cannot but adore. And there is no difference whether they simply worship an idol, or God in the idol. It is always idolatry when divine honors are bestowed upon an idol, under whatever pretext this is done. And because it does not please God to be worshiped superstitiously, whatever is conferred upon the idol is snatched away from Him. (1.11.9)

Here, Calvin denies the Christian distinction between veneration and adoration—perhaps most famously explained at the Second Council of Nicaea (A.D. 787). Stated briefly, veneration or honor can be paid to honorable men (for example, kings and royalty, along with clergy), angels, and even relics or the Cross, while adoration (λατρεία) is given to God alone.

While exposited more fully at the Seventh Ecumenical Council, this distinction is thoroughly biblical. The scriptures provide numerous examples where a person or object is venerated, and without it being mistaken as idolatry (or the worship due God alone): Leah and her children, along with Rachael and Joseph (Gen. 33:7); Absalom before the king (2 Sam./Kings 25:23); a woman before a man (1 Sam./Kings 25:23); a woman before a prophet (2/4 Kings 4:37); and even priests before the ark of the covenant, which was adorned with statues of the cherubim (Psalm 98/99:5)!

And I should add, it seems a denial of both human reason and experience to claim the honor paid to relics or images does not pass along to their prototypes. When Americans salute their flag, they are not honoring cloth and ink. When a lonely wife kisses a photo of her husband while he’s away on business, she is not honoring a piece of paper (or cell phone screen). When a child hugs close to them a gift from their recently deceased grandparent, they are honoring the giver, not the gift itself. Veneration is all around us, and no one mistakes it for the worship of idols.

Calvin again reproaches the distinction beween veneration and adoration:

The honor that they pay to their images they allege to be idol service, denying it to be idol worship. For they speak thus when they teach that the honor which they call dulia can be given to statues and pictures without wronging God. Therefore they deem themselves innocent if they are only servants of idols, not worshipers of them too. (1.11.11)

This goes back to the meaning of both idols and idolatry. What is an idol? What is idolatry? Calvin seems incapable of making the simple distinction between a statue of a false deity and that of Christ and his friends. This seems to me both obstinate and absurd. There is a gaping chasm between the worship (whether veneration or adoration) given to idols and the honoring of Christ, his holy Mother, angels, and Saints.

The object of our devotion is neither wood and paint nor the legions of Satan—it is Christ and those who have shown forth Christ in all humility and self-sacrifice for the life of the world. It is no different than honoring the saints of old in Hebrews chapter eleven, the “great cloud of witnesses” that encourages the faithful as we strive to finish the race set before us (Heb. 12:1).

Finally, Calvin derides Orthodox Christians specifically in their (primary) usage of two-dimensional iconography:

But we must note that a “likeness” no less than a “graven image” is forbidden. Thus is the foolish scruple of the Greek Christians refuted. For they consider that they have acquitted themselves beautifully if they do not make sculptures of God, while they wantonly indulge in pictures more than any other nation. But the Lord forbids not only that a likeness be erected to him by a maker of statues but that one be fashioned by any craftsman whatever, because he is thus represented falsely and with an insult to his majesty. (1.11.4)

The background here is a wordplay that is somewhat lost in English. The idols of the second commandment are “scupltured images” (Heb: פֶּ֫סֶל from the root פסל, meaning to “hew” or “cut”), implying three-dimensional images. Since most Orthodox iconography (at least during this time) was two-dimensional, Calvin aims to prove that we Greeks are not free from his condemnations of idolatry.

But again, the Orthodox objection to this artistic fundamentalism is in its denial of the Incarnation. If God could become truly man—being the very image of God—then true depictions of other images of God are not only possible, but also acceptable. Without image-making, there is no salvation. God fashioned an image according to his own for our salvation.