Source: modeoflife.org

By Fr Brendan Pelphery

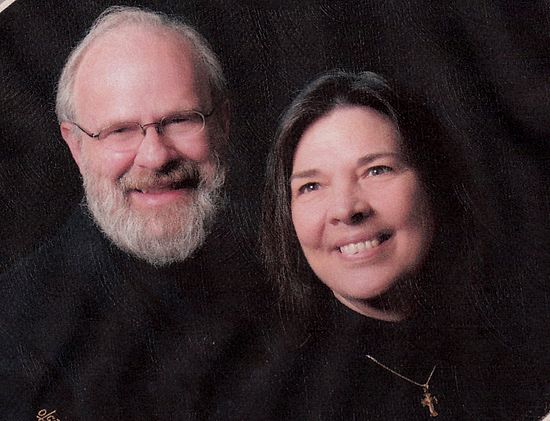

Converts to Orthodoxy are frequently asked why we became Orthodox. Since my wife and I were chrismated in 1995 we have answered this question hundreds of times, but often it is difficult to know exactly what to say. It is not that our story changes each time, but that the reason for asking can be different for different people. But first a word about how we became Orthodox.

In our particular case, the process took many years—more than a quarter of a century, altogether. The process began in graduate school, when we first heard of the Orthodox Church (we didn’t know anything about it before); or actually a bit before that, when my wife and I began going to church once again after a time of separation from Christian faith altogether.

When we met in high school, my wife was an agnostic, and my family were pious Lutherans. I was beginning to have doubts, however, about Protestant churches in general, and as a Philosophy major in college enjoyed exposure to Hinduism through various channels, including a Hindu professor. Ultimately I began to investigate all sorts of churches and faiths and ideologies, including Hinduism, astrology, ESP, eclectic mysticism, native-religions, and basically anything I could read about religions and world spiritualities.

Although we married in a Lutheran church, there was no real sense in which my wife and I were Lutheran Christians at that time. Later, in medical school, I visited nearly every church in the city in search of something which seemed to make sense. Awed by the experience of seeing life and death up-close, I experienced a kind of spiritual crisis. I did not think any churches had the answer. I wanted some kind of deep mystical experience personally.

I left medical school and was drafted into the Army, where I escaped death on several occasions. Once, a medic was killed in Vietnam; I was supposed to be there in his place, but my flight had been delayed and I did not report on time. In another case, a man tried to kill me, but I was frightened into praying aloud, and he began to weep, putting down his weapon. This gave me a sense of the power of prayer and of the presence of God. Encountering the “Jesus People” in the Army, my wife and I began to go to church—any church—and to wonder if Jesus Christ is truly the Answer to the questions of life.

I decided to go to graduate school to learn more about world religions. At the University of Edinburgh (Scotland) I studied Hinduism and Christianity. A central part of the studies there was the study of Patristics—that is, the writings of the early Christian Fathers or theologians of the Church. Here my wife and I learned about Christian mysticism, about the origins of the Church and about the Eastern Orthodox faith. We also began reading about Orthodoxy for the first time.

Today, Orthodox Americans are familiar with the books of His Eminence Metropolitan Kallistos of Diokleia (Timothy Ware), who in 1958 joined the Orthodox Church in England. Metropolitan Kallistos converted during a period of great interest in Orthodoxy at Oxford University, influenced by teachers such as Derwas Chitty, Fr. Lev Gillet and Metropolitan Anthony (Bloom) of blessed memory. For several decades the Fellowship of St. Alban and St. Sergius in London, with its St. Basil’s House, promoted Anglican-Orthodox dialogue and led to a much greater understanding of Orthodoxy by clergy in Great Britain. The interest in Orthodoxy at Oxford influenced other students in other institutions, including ourselves.

At the University of Edinburgh our first spiritual father was a Roman Catholic hermit-monk, Fr. Roland Walls, who teaches and lives according to the tradition of the Desert Fathers (Christian ascetics of the third to fifth centuries, who lived in the deserts of Egypt and Palestine). He had been educated at Cambridge where, beginning in the ‘30’s, students had been deeply influenced by Orthodoxy.

Also at Edinburgh one of our teachers was Prof. John Zizioulas, who is now His Eminence Metropolitan John of Pergamon. His lectures on Orthodox theology opened up a new world for the students there. Finally, the priest of our local Episcopal church in Scotland was himself a part of the movement towards Orthodoxy at Oxford, and though Episcopal, spent hours in prayer every day.

Through all these avenues we became familiar with Orthodox churches; but at that time, we thought that only Greeks or Russians or Arabs could be Orthodox. We did not realize that it would be possible for someone else to join the Orthodox Church. But by now we were becoming convinced Christians, and we began to experience the blessings of an in-filling and renewal in the Holy Spirit. We worshipped with Christians of many different backgrounds, and were accepted everywhere. Eventually I was ordained as a Lutheran pastor, but not before having lived for several months in an ecumenical Christian commune, working for an Episcopal bishop, and worshipping regularly with Roman Catholics as well as independent, evangelical and Pentecostal Christians.

As Lutherans, we eventually became missionaries in Hong Kong, travelling throughout Asia in dialogue with Buddhists and teaching converts to Christianity both in a Lutheran seminary, and elsewhere. We were always in dialogue with Orthodox Christians during this time, but we continued to worship with Christians of every possible background. Returning to America, I served in a local Lutheran church and in campus ministry, while teaching at various universities. At this time we met a local Greek Orthodox priest and began attending Orthodox worship. After several years I resigned from the Lutheran church, and we were chrismated and married in the Orthodox Church.

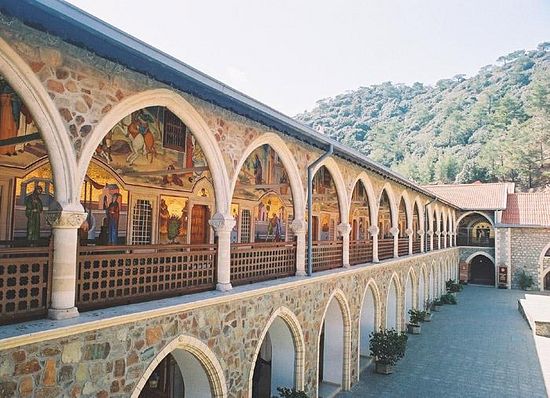

We traveled to Boston where I studied at Holy Cross Greek Orthodox School of Theology, at the same time teaching at Hellenic College in Boston and at St. Sophia Ukrainian Orthodox Seminary in New Jersey. I was also sent overseas to spend several months in Cyprus, at first living at Kykkos Monastery in Nicosia, and eventually joined by my wife in a Cypriot village. This experience was life-changing for us, as we saw the Orthodox faith first-hand in village priests and the people, who were very kind to us. We saw a miraculous icon at Kykkos (which began “weeping” myrrh during our visit, attracting tens of thousands of visitors to the monastery); we heard the Divine Liturgy in its native Greek and attended daily Orthros (morning prayers) and Vespers in the village. Back in America, in time I was ordained as a deacon and then as a priest, and served as an Assistant Priest and now as a Proistamenos of my own parish.

Orthodox friends are sometimes curious why “Americans” would want to become Greek Orthodox. After all, in the Greek Archdiocese the Greek language is ever-present in liturgies as well as in casual conversations. Greek is a comparatively difficult language to learn. Wouldn’t it be easier to join some other kind of Orthodox Church, or simply to remain what we were before?

The first thing to understand is that there are serious spiritual reasons for becoming Orthodox. Today there is a growing recognition that Orthodoxy is “original Christianity” and that there is no other true Church. Protestants who convert to Orthodoxy do so because they thirst for Truth, and for the spiritual blessings of being Orthodox Christians. In our case, it would have been impossible not to become Orthodox, even if joining the Church required sacrifices on our part.

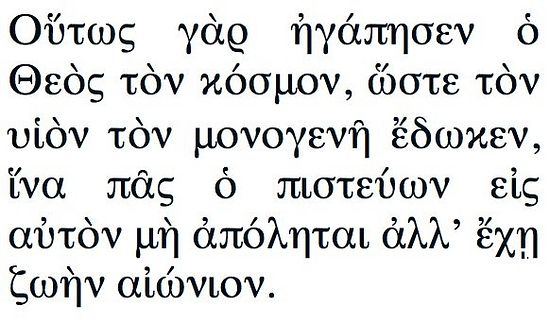

Deciding which jurisdiction to join took more time. Admittedly, Greek is difficult and sometimes it has been discouraging not to know what is being chanted or read. But Greek is the language of the Bible, and there is something precious in learning to understand the ancient language of the Church and to hear it in the Divine Liturgy. Byzantine chant never sounds quite the same in English. There were times when we wanted to participate in Orthodox worship entirely in English, and occasionally we were able to. On the other hand, we found that we were becoming attached to the ancient worship in Greek, and we began to enjoy it.

More important for us, however, was the sense that people should come to Orthodoxy locally, wherever they find themselves. Over the years we had spoken with Orthodox clergy of a variety of jurisdictions and were most familiar with the publications and recorded music of the OCA (Orthodox Church in America, of Russian background). However, in our home town we became acquainted with a Greek Orthodox priest, Fr. Nicholas Triantafilou (now President of Hellenic College/Holy Cross Greek Orthodox School of Theology) who welcomed us with great warmth and enthusiasm whenever we visited his congregation. From the beginning we knew that this was our “family.”

Occasionally there is someone who believes that Greek Orthodoxy should be only for Greeks. Mykoumbaro, who is originally from Cyprus, told me that when we were chrismated one of his friends said to him,

“The sign on the church says Greek Orthodox.”

He meant that we were not Greek, so we did not belong there. Our sponsor replied,

“Read the rest of the sign. It also says, of America.”

Now we are “adopted Greeks.” Others may find themselves becoming “adopted Russians” or Syrians or Romanians, Bulgarians or Serbians or Ethiopians. But Orthodoxy in America today is becoming “American,” and in the meantime enjoys a real experience of Pentecost, as we come together from many different backgrounds and languages. In our own congregation today the people represent about twelve different languages and many different ethnic, racial and faith- backgrounds. This variety of backgrounds (which is much wider than in typical Roman Catholic or Protestant churches) is inspiring and gives us a real foretaste of Heaven.

Today the reality is that the Church is growing in America, as overseas, and not only because men and women marry into the Greek-American community. More and more, Greek Orthodox parishes are experiencing an influx of newcomers who inquire about conversion. Our own parish of St. George is growing rapidly as families come to us who either have no church background, or who are pilgrims in search of the ancient Church, the Body of Christ.

Inevitably there will be growing pains as more and more members of American congregations, as well as priests, are non-Greek. But this is a good problem for the Church to have. The Church is the Body of Christ. It is not ours, but His, and we are all sheep of His pasture. Besides, converts enjoy learning about Greek culture, even if it is sometimes difficult to follow Orthros or to communicate with new friends.

Occasionally, friends ask about our conversion because they themselves are contemplating going awayfrom the Church. They do not understand why someone would deliberately change their faith or join an Orthodox congregation.

“Look at all the problems,” they say. In this case, our answer is to testify to the truth of Orthodoxy and to the splendour of Orthodox faith and worship. This is the Church of Christ. This is where we, and they, belong. Moreover, we do not see deep problems in the Church. There can be difficult individuals anywhere, but in our parish we find the people to be pious and faithful, and our friends. There is real Christian faith here.

Some friends assume that becoming Orthodox means rejecting everything we were taught before. Certainly there are many things in our Protestant upbringing with which we would no longer agree. On the other hand, for most of us it is not a question of rejecting everything we knew before, but of seeing it all in a new light. We have been on a life-long journey to Truth. Before, we knew the Truth in part; now we have come to the fullness of Truth. We are learning the gospel of Christ “more perfectly” (Acts 18:26).

Sometimes, however, the change to Orthodoxy involves a more radical change. A few years ago a minister wrote to me that Orthodoxy must be more or less the same as his Protestant faith, but with additions such as icons and a reverence for the Mary, the Theotokos (Mother of God). I replied that his understanding of Christianity was upside-down. To become Orthodox he would have to gain a completely new “mind” or perspective (what the Greeks call phronema). It would be like starting all over again, and it would mean understanding everything—the Holy Trinity, creation, Christ, salvation, worship, the Church—in a new way. At first he was startled, but later he thanked me because this was the insight he needed to become Orthodox.

A few friends have asked, “Aren’t converts tempted to change their minds again? Will they stay Orthodox?”

To be sure, converts have already changed their minds about many things or they would not have become Orthodox. However, this does not imply that they will change again. Most of us have left everything to follow Christ into His Church. We are home now. Like the Apostle Peter we say to Christ, “Lord, to whom would we go? (John 6:68)”.

Finally, the question is sometimes raised whether converts can really learn the Orthodox faith in a relatively short time. Doesn’t it take many years to gain an Orthodox perspective? It is true that in some ways older catechumens are “behind” their brothers and sisters. But on the other hand, the intentional study which goes with chrismation can be far more intense for converts than the education which “cradle Orthodox” have received. The difference is that in one case the learning may be largely from books, while in the other case it is through a lifetime of experience. Both are valuable.

Occasionally Orthodox friends say that former Protestants are more familiar with the Bible than they are. Often this is true, because of the role the Bible plays in Protestant churches. Former Protestants are more likely to have read the whole Bible, and many have memorized portions of the Scriptures in childhood. However, Protestants do not usually have the experience of hearing the Scripture quoted in the Divine Liturgy or placed in the context of the Sacraments; and in the past they interpreted the Scriptures for themselves. For this reason their understanding of the Bible was often incorrect. Here, converts and “cradle Orthodox” can help one another.

Converts may also be more conscious of Orthodox Tradition, or even of Church canons. The reason is that becoming Orthodox is a process of submitting to the Tradition of the Church in order to learn its theology and prayer. Ultimately, making the decision to become Orthodox means making the decision to let the Church lead us. So we go to our spiritual Father, or to our koumbaro or koumbara (our sponsor in baptism), and we ask for advice and guidance. We expect to receive guidance from our bishop. This is something which “cradle-Orthodox” have sometimes forgotten. Above all, we are conscious that we want to be guided by the Holy Tradition as a whole, in our personal lives from day to day.

Converts often embrace the rules of fasting, for example, because it is a new experience for them and because in the past they did not regulate such practices through the Church year or during the week. (Some Protestants may have fasted in the past by taking neither food nor water for as long as a week at a time.) It is a joy now to be guided by the wisdom of the Church, and not to make these decisions for ourselves.

How long does it take to convert? It is not always easy to obtain chrismation. In our case there were no Orthodox churches nearby when we first became interested in the Church. Others find discouragement because of the language barrier. In any case, today it is not difficult to locate nearby Orthodox churches and to begin the process of learning (called catechesis). From the moment you decide to become Orthodox and to learn, you are a catechumen and so you are part of the Church. For most, there will be a process of study for several months or a year; but learning never ends, even for those who were born into Orthodox families.

What if you cannot decide whether to become Orthodox?

The fact is that you will be changed by it, nevertheless. While many of the Oxford students in the 1950’s and ‘60’s did not convert, Orthodoxy nevertheless influenced their understanding of the Christian faith, their personal prayer and ways of worship. The long-range effects of the university movements will be felt for generations to come.

In reflecting on the phenomenon of conversion which is taking place today, we might do well to focus attention not on the ethnic or religious background of converts but on the nature of the Church itself. The Church is the Body of Christ on earth. Since the first Pentecost it has drawn people from every ethnic and linguistic background. The question is whether we in the Church are willing to be “perfectly one” in Christ, as Christ is One with the Father (John 17:20 ff.).

Let us pray for this, as we pray for “ourselves, and one another, and for our whole life in Christ our God.”

Fr. Brendan is the priest of St. George Orthodox Church in Shreveport, Louisiana.