Mitred Archpriest Michael Li, head of the Russian-Chinese Orthodox Mission of the Russian Church Abroad in Australia, a priest of the Croydon Church of All Saints of Russia, turned ninety in January of this year. Fr. Michael is the last priest of the Orthodox Church in China ordained back in the time of the Peking Spiritual Mission who still continues to serve regularly. Fr. Michael tells our readers about his life, the history of Orthodoxy in China, and suffering for the faith during the years of the Cultural Revolution. [This interview was translated from the Russian]

—Fr. Michael, may I ask you a few questions?

—Yes. But I don’t speak very good Russian. I lost my Russian language. I was in exile from 1966, spent twenty years doing manual labor (forced labor in a stone quarry.—Ed.). I lost the right to speak. During that time I forgot everything, and I was forbidden to say a word in Russian. But earlier I knew Russian well, we were taught well. In 1966 we were evicted from our home, and I was sent to do hard manual labor. This was because of our Orthodox faith.

—Not much is known about that period of Orthodox Church in China. Could you tell us about what happened at that time?

—It was a bad time. The Russian Spiritual Mission was closed. All the parishioners were evicted. We lost everything. We were then living in the church apartment. We were evicted and given a very small room, with no kitchen, water, electricity, or toilet. We lived there twenty years with four children. I was forced to work in the stone quarry, where I was supposed to excavate a ton of rock per day. It was hard, hard. Then I was given freedom.

In 1986, they opened the Orthodox Church in Harbin. I was offered to serve there. But people from the “organs” watched, summoned [the priests], and asked about the parishioners: What did they say? What did they do? I didn’t care for this, I didn’t want to participate in it. I did not go to serve there. But one parishioner from Harbin told Metropolitan Hilarion (Kapral) from the Russian Church Abroad—he was then in Australia—that Fr. Michael Li is still alive, living in Shanghai. And His Eminence invited me, helped me move, and I began serving in Australia.

—During the time of persecutions, when you were exiled and did hard labor, what helped you to keep your faith?

—Reading prayers. But I had to pray secretly.

Metropolitan Hilarian and Fr. Michael Li in Croydon, Australia

Metropolitan Hilarian and Fr. Michael Li in Croydon, Australia

—Tell us about the time of your childhood, when Orthodoxy in China was at its peak.

—I was born in Peking, in Bei Huan, in the Russian Spiritual Mission. The Mission territory was very large, a whole complex. There was a print shop, a dairy farm, and much else. All the workers were Orthodox. It was a very good time. My father, Gregory, studied in the seminary, and was thinking about monasticism, but then he got married just the same. He had six children, and I was the oldest. At age seven I went to school, there on the Mission territory. It was called the Russo-Chinese Orthodox School. From age ten I sang in the church choir; we were taught everything, how to read notes, and I sang the first part [soprano or tenor]. I used to sing well, but after twenty years of hard labor I forgot everything… Now I remember very little. When I was little I loved the church and praying very much. In Peking, in the Spiritual Mission, the choir loft was very high. It was beautiful. Every Pascha, after the service I would stay all night there. I very much loved the services.

—Were there many Orthodox Chinese in Peking at the time?

—Yes, many. Almost two thousand.

—Who was your first spiritual father?

—Archbishop Victor. There were three bishops [as heads of the Mission] in China in my day. The first was Metropolitan Innocent.1 He was very strict. When someone did not obey, he would punish him. The second was Archbishop Simon,2 and the third was Archbishop Victor,3 who later left for Russia. He ordained me a priest in 1952.

Farewell photograph of Archbishop Victor with workers at the dairy. Peking, Bei Huang, 1956.

Farewell photograph of Archbishop Victor with workers at the dairy. Peking, Bei Huang, 1956.

—How did that come about?

—After school I went to seminary. There were twenty of us at the Mission school, but many studied poorly, they just played. Three were ordained priests from our school: the first was Monk Thaddeus, the second was Evangel, and I was the third. Thaddeus became a deacon first, and later, during the [cultural] revolution he was killed. Deacon Evangel is still living, in Shanghai. Not long ago he fell and broke his leg, and now lies in bed—he can’t walk. I am the only one left who serves.

—When you finally served your first Divine Liturgy in Australia after a long hiatus, what did you feel?

—I was very glad. But I was worried because I had forgotten so much. They gave me everything—the Gospels, a service book, and the Book of Needs. But I had completely forgotten how to serve. And can you imagine, I remembered everything at the first service!

—Did you see St. John of Shanghai?

—Yes. Once he came to Archbishop Victor and served the Liturgy in Peking, and I served with him, received his blessing, Holy Hierarch John. He was small in stature.

—What about your family? Where they able to preserve their Orthodox faith?

—Yes. But my children stayed in Shanghai, and I came to Australia with only my matushka.

—When you were ordained a priest, did you serve in Chinese or in Church Slavonic?

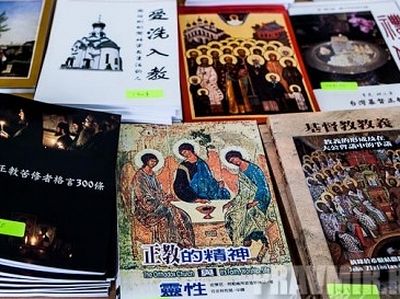

—At first in Chinese—the Gospels, and almost everything else, very little in Church Slavonic. I had the Gospels, a service book, and the Book of Needs in Chinese… Many books. Later they confiscated them all and burned them.

—Are there Chinese Orthodox among your parishioners in Australia?

—Yes, many. They came from Gwangzhou. Some of them did not know English, or Russian.

—What do think about the future of Orthodoxy in the Chinese lands?

—I don’t know what will happen in the future. It is hard to say. Now in China every word, every deed is mixed up with politics. But a Christian must be beyond politics. We have to be patient. Only pray. God will set things aright. He knows everything. All our hope is in Him.