Do not be yoked together with unbelievers. For what do righteousness and wickedness have in common? Or what fellowship can light have with darkness? What harmony is there between Christ and Belial? What does a believer have in common with an unbeliever? What agreement is there between the temple of God and idols?

1 Corinthians 6:14–18 NIV

I was raised Roman Catholic. I loved prayer. Walks through woods, playing in creeks, running through the vast fields of the imagination. These were like prayer for me: the silence, the stillness, the hesychia children find themselves in almost by nature. I didn't always stay in this prayerful place. But I recognized it. And I took it for granted, as a simple activity within the heart.

We all experience this to varying degrees. We use different words—or none at all, because they all seem so inadequate—to express the heart's movement toward God. It seems when we are innocent in heart, especially when we are very young, there is a tangible perception of two in these experiences. Lover and Beloved. The Someone Else. As I child, I didn't articulate this Presence as Christ—just as I never articulated my parents by their names. I just knew them.

* * *

As a high school student—my grandparents put me through an all-boy Roman Catholic high school—I wanted to be a Trappist monk. I attended services regularly and read the Bible often. Scripture really is like a door. You can enter through it and the Holy Spirit takes you places without ever really lifting your shoes off the ground. But I knew there was something more. A difference between reading about the experiences and the experience Himself.

Dr. Harry Boosalis writes in Holy Tradition: "We are not called simply to 'follow' Tradition or 'mimic' Tradition. We are called to experience it...just as the Saints have and continue to do." We know something is missing in the world around us. Some richness, some depth we are vaguely aware of and long after. This is, of course, the richness of God's love, light, and grace. But, at that time of my life, I didn't have the language to express this. Like so many, I attributed this dissatisfaction, this unease, to other things.

Then a psychology professor in high school guided my class through self-hypnosis. My intrigue with meditation followed quickly thereafter. I felt relaxed. I let my guard down to new experiences. I felt as if the back door of my heart opened permanently. I rejected God 'to go it alone on my own.' I experienced, very clearly, a light switching off inside me. The Presence, the Someone Else, the Friend respected this decision. It felt as if He quietly left. He respects freewill. He never forces Himself. He knocks on the door of the heart and waits.

* * *

So I started meditating regularly. Initially, especially as a teenager, it was really difficult: sitting for hours with old Tibetan Buddhists, completely still, bringing my thoughts back to the bare wall and bronze statue of the Buddha in front of me. I started studying reincarnation, karma, and samsara.[1] I wasn't yet aware of Tibetan Buddhism's origins in the shamanistic religion called Bon, nor its embrace of astrology, magic, and other occult practices.[2]

I wanted to learn how to calm anxiety and depression, how to sweep scattered thoughts. Visiting Buddhist meditation halls and Hindu ashrams, I was intrigued by the 'spiritual fireworks:' the ecstasies, trances, feelings, and visions. These are associated with all levels of meditation and yoga and increase with practice. These experiences and more are sometimes referred to as siddhis, or powers acquired through sadhana (practice of meditation and yoga). Intrigue became fascination, and the fascinating became familiar. Without my noticing, my initial 'harmless' curiosity of the yoga and meditation hardened into habit. I spent more than a decade immersed in this spiritual sea.

During these years, lots of questions were asked. For instance, do Roman Catholic priests and monks know whether early Christians believed in the pre-existence of souls and reincarnation? They said they didn't know. And besides, they asked, what does it matter? Reading further into the origins and meanings of Far East religions, and eager to experience the bardos—the intermediary dimensions of the material and spiritual worlds—I studied the Tibetan Book of Living and Dying.

I read all the mystical or esoteric literature I could get my hands on and kept a copy of the Bhagavad Gita folded in my back pocket and read the writings of Paramahansa Yogananda. I immersed myself in the writings of Osho, read Ram Dass and Ramana Maharshi, convinced there was no being more divine than myself. It was up to me to shatter my illusory self. According to so much of what I read and heard there can be no personal relationship with the Divine and this conflicted me. The calm and peaceful nature of childhood was gone. The more I delved into the meat of meditation and yoga, the more sudden and unexplainable urges I experienced to hurt myself. My soul was under attack. This was a very dark and unfortunate period of my life.

Seeking calm, I took the Bodhisattva vow and sought a contemplative and peaceful lay monastic order within Buddhism in an effort to ground myself somewhere, with something. After an initial period of relative peace, boldness developed, even recklessness, concerning spiritual activities. I was going through a sort of spiritual alcoholism. But I didn’t know it.

* * *

The Prodigal Son ate the food of pigs in a far country. But he returned home when he remembered the taste of the Bread of his Father's house. For more than a decade I lived in this far country, eating its food.

I saw so many people—some friends, many strangers—seeking the dissolution of self. They had an insatiable desire to lose themselves, not in the life and light of God but in the darkness of the void, in a separation from the Love Who Transcends Everything. This separation is hell. Many men, women and children seek this hell, spinning through promiscuous relationships and leaping out of the windows of drugs, through which so many fall.

But I studied and practiced Kundalini Yoga and shamanism, learning the presence of fear and coldness.[3]

I grew a reputation for reading the tarot, an occult method of divination. I taught yoga and instructed groups through guided meditations and chanting in sage deserts. We experimented with astral projection – guided out-of-body experiences through the bardos described in the Tibetan books. I carried not only underlined copies of the Bhagavad Gita, but of the Upanishads and sutras of the buddhas everywhere I went.[4] Every one of these pursuits was a swim stroke away from the holy mountain of Christ. Drop water on stone long enough and you'll whither it away. Swabbing orange paste across my forehead, I rang bells offering fruit and fire while worshipping Krishna, wandering barefoot the streets of Eugene, Portland, Seattle and finally Rishikesh, Haridwar and Dharamsala in north India.

* * *

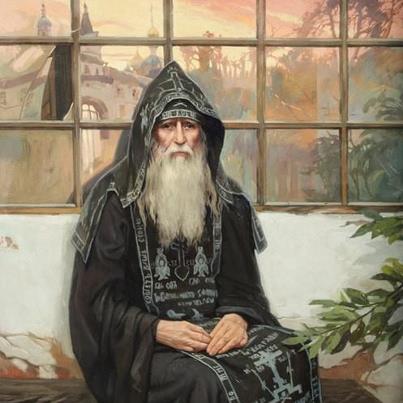

Archimandrite Zacharias of Essex

Archimandrite Zacharias of Essex

Buddhism rejects the self, the soul, and the person. It folds its arms in silence against God. Suffering is never transfigured. There are crosses in Buddhism but there is never resurrection. One could say that Buddhism finds the empty tomb and declares this emptiness the natural state of things, even the goal. In Buddhism everything—heaven, hell, God, the self, the soul, the person—is an illusion waiting to be overcome, discarded, destroyed. This is the goal. Total obliteration. In this 9th-century axiom, the essence of Buddhism is summed: 'If you see the Buddha, kill him.'

Buddhism does not profess to—nor can it—heal soul and body. Both soul and body are to be overcome and discarded. In the Orthodox Church, however, the soul and body are meant to be healed. Buddhism teaches that nothing has intrinsic value. The Church teaches that everything God makes has intrinsic value. This includes the human body. We are complex beings. The actions of our body, mind and soul are linked. And these linked actions are directly related to our relationship with God and the spiritual realm.

For Orthodox Christians, everything—even suffering—is a hidden door through which we meet Christ, whereby we embrace one another.

* * *

One autumn, I traveled to Rishikesh, India. This city is named after the pagan god Vishnu, ‘the lord of the senses.’ Rishikesh is the 'yoga capital of the world.' It is generally accepted to be the place on earth where yoga originated from. For 40 days I studied and practiced the so-called secret spiritual path of integral yoga in the foothills of the Himalayas.[5] This covered not only the gym yoga of America; each class began and ended with a prayer to ‘the god of the roaring storm,’ Shiva.

This is while I was teaching English to Tibetan refugees and working for the Tibetan National Government as an editor. Yoga is historically rooted in Hinduism. Curious, I spoke with a rinpoche at the Dalai Lama's monastery in Dharamsala.[6] I asked him who or what these Hindu gods are according to Buddhist cosmology. His answer is alarming: “They are created beings, with an ego...they are spirits trapped in the air."[7]

* * *

What is yoga? What is kundalini energy?

The literal meaning of yoga is 'yoke.' It means tying your will to the serpent kundalini and raising it to Shiva and experiencing your 'true' self. All paths of yoga are interconnected like branches of a tree. A tree with roots descending into the same areas of the spiritual world. This is evident in the ancient books the Bhagavad Gita and the Yogic Sutras of Patanjali. I learned that the ultimate goal of yoga is to awaken the kundalini energy coiled at the base of the spine in the image of a serpent so that it brings you to a state whereby you realize Tat Tvam Asi.[8]

Of course, yoga may facilitate exceptional experiences of body and mind. But so does the ingestion of mind-altering drugs, and flavorless, imperceptible poisons. Through yoga, little by little, one is harnessing shakti, which yogis refer to as the Divine Mother, the 'dark goddess' connected with other major Hindu gods. This energy isn't the Holy Spirit, and This isn't aerobics or gymnastics. Attached to this entire system are bhajans and kirtans – pagan equivalents to Orthodox Christian akathists, but for Hindu gods – as well as mantras, which are 'sacred' formulas, like calling cards or phone numbers, to the various pagan gurus and gods.

* * *

How is yoga connected with Hinduism?

To be clear, Hinduism does not refer to a specific religion. It is a term the British gave to the various cults, philosophies and shamanistic religions of India. If you ask one Hindu if he believes in God, he may tell you that you are God. But ask another, and he will point to a rock, or statue, or a flame of fire. This is Hindu polarity: either you are God, or everything else is a god.

Yoga is beneath this umbrella of Hinduism, and in many ways is the pole of the umbrella. It acts as a missionary arm for Hinduism and the New Age outside of India.[9] Hinduism is like an extraordinary Russian nesting doll: you open one philosophy and within it are ten thousand more.

And the unopened ones are risks. You may swim easily and carelessly in waters you do not know. But unaware of the tides and nuances of the area, you may be in danger. You may be swept away by the undertow. You may cut yourself against unseen rocks and contract imperceptible infection and poison.

This happens in the spiritual life.

When we dive in the ocean, we may be attracted to the brightest, most colorful and intriguing fish but the most colorful and exotic are often the most poisonous and deadly.

The first time I visited India, I took off my shoes and socks and walked through the water, coconuts, discarded candy and shimmering fire of Kalkaji Temple. It is one of the most famous temples dedicated to Kali, ‘the goddess of death.’ I didn't know it, but I was right in the middle of her most important festival of the year. The temple was chaos and the energy very heightened and dark.

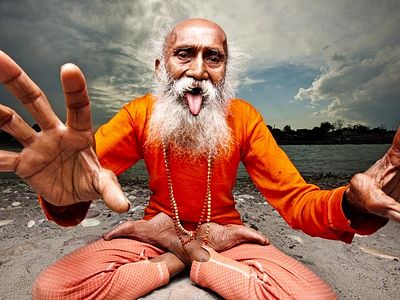

Thousands of men, women and children gathered at this Rishikesh temple to worship this demon. Next to me, a woman's eyes rolled back in her head, arms waving back and forth, tongue wagging pink from her mouth, legs lifting and falling like a puppet on strings. This was clearly demonic possession.

Once, I venerated the Sitka Mother of God icon[10] and experienced incredible warmth, tears of humility and love, mental clarity, and peace. It was like walking in front of a window full of warm, fragrant sunshine. At Kalkaji temple, I experienced the opposite.

I have drank coffee with people instrumental in the movement of yoga, Hinduism and the New Age in America who, in order to be initiated into her cult, were prompted to eat human corpses from Nepalese graveyards. Not too long ago, the popular British newspaper The Guardian reported that child sacrifices continue to this day, honoring this demon Kali.[11] This is all connected to Hinduism. And it is connected to yoga because the postures of yoga are not religiously neutral. All of the classic asanas have spiritual significance. For example, as one journalist reports, the Sun Salutations,—perhaps the best-known series of asanas, or postures, of hatha yoga—the type most commonly practiced in America—is literally a Hindu ritual.

“Sun Salutation was never a hatha yoga tradition,” says Subhas Rampersaud Tiwari, professor of yoga philosophy and meditation at Hindu University of America in Orlando, Florida. “It is a whole series of ritual appreciations to the sun, being thankful for that source of energy.”[12]

To think of yoga as a mere physical movement is tantamount to “saying that baptism is just an underwater exercise.” writes Swami Param of the Classical Yoga Hindu Academy and Dharma Yoga ashram in Manahawkin, N.J.[13]

It is the goddess Kali who attempts to unite practitioners through shakti with Shiva by means of yoga. At her temple just outside New Delhi, I saw the hideous 'self-manifested' idol: a rock with strange, beady eyes, beaked and covered in yellowy slime and curdled food. In Hinduism, idols are 'woken up.' They are dressed. They are fed. They are sung to. And they are put to sleep. I've been part of hundreds of these ceremonies.

With more than five million readers, Yoga Journal is the best-selling yoga magazine in the world. In a revealing moment regarding the superiority of yoga as psychotherapy, Yoga Journal revealed the Hindu philosophy behind the practice:

“From the yogic perspective, all human beings are ‘born divine’ and each human being has at its core a soul (atman) that dwells eternally in the changeless, infinite, all-pervading reality (brahman). In Patanjali’s classic statement of this view...we already are that which we seek. We are God in disguise. We are already inherently perfect, and we have the potential in each moment to wake up to this true, awake, and enlightened nature.”[14]

Teachers and students typically greet each other with the Sanskrit ‘namaste,’ which means, “I honor the Divine within you.” This is an affirmation of pantheism and denial of the true God revealed in the Bible. The Sun Salutations, or, Surya Namaskara, originated with the worship of the Hindu solar deity Surya.

In Church hagiography and iconography, we venerate saints—real people who lived righteously before God and participated and continue to participate in His light and love—asking their intercessions. Idols, on the other hand, writes Fr. Michael Pomazansky, “are the images of false gods, and the worship of them was a worship of demons, or else of imaginary beings that have no existence; and thus, in essence, it is a worship of the lifeless objects themselves.”[15]

I have seen swamis – in this country, in America – transmit this demonic kundalini energy just by looking in a person's eyes. And if one is open to it, the body may shake and vibrate like a tin windup toy.

And yet when it came time for me to receive this cursed energy through Shaktipat, an unbelievable fear washed over me like cold, electrified water so I raised my shield and sword: I started saying the Jesus Prayer.[16] Glory to God! This awful presence was deflected by the Name of Jesus. We must remember, as St. Paul writes, We do not wrestle against flesh and blood, but against principalities, against powers, against the rulers of the darkness of this age, against spiritual hosts of wickedness in the heavenly places.[17]

With that prayer as my shield and sword, I swam a stroke back towards Christ. I took a step out of the far country. I took a step into my Father’s House.

* * *

How is yoga connected to Orthodoxy?

Yoga is a psychosomatic practice, an interaction between mind, body, and spirit(s). We must remember the word ‘yoga’ means 'yoke,' like the wooden crosspiece fastened over the necks of animals attached to the plow. St. Paul warns us, Do not be unequally yoked together with unbelievers. For what fellowship has righteousness with lawlessness? And what communion has light with darkness?[18]

Yoga isn't Scriptural nor is it otherwise part of our Church’s Holy Tradition. Everything we're looking for, everything, can be found in and through the Orthodox Church. So what would we want from yoga?

Furthermore, something should be said in relation to the claim that ‘pop’ forms of gym yoga carry no danger or threat to a practitioner. Someone who holds such an opinion is either ignorant of, or chooses to ignore, the many warnings that appear in the eastern yoga manuals concerning the Hatha yoga that is practiced in such classes. Is the instructor aware of these warnings and able to guarantee that no harm will come to the student?

In his book Seven Schools of Yoga, Ernest Wood begins his description of Hatha yoga by stating, “I must not refer to any of these Hatha Yoga practices without sounding a severe warning. Many people have brought upon themselves incurable illness and even madness by practicing them without providing the proper conditions of body and mind. The yoga books are full of such warnings…. For example, the Gheranda Samhita announces that if one begins the practices in hot, cold or rainy weather, diseases will be contracted, and also if there is not moderation in diet, for only one half the stomach must ever be filled with solid food…. The Hatha Yoga Pradipika states that control of breath must be brought about very gradually, ‘as lions, elephants and tigers are tamed,’ or ‘the experimenter will be killed,’ and by any mistake there arises cough, asthma, head, eye and ear pains, and many other diseases.” Wood concludes his warning about posture and breathing yoga by saying, “I should like to make it clear that I am not recommending these practices, as I hold that all Hatha Yogas are extremely dangerous”.[20]

If an Orthodox Christian wants to exercise, he or she may swim, jog, hike, walk, and do stretching exercises, aerobics, or Pilates.[21] These are safe alternatives to yoga. We can also offer prostrations before God. The Church doesn't want any of us to be unhealthy or unhappy. We should trust the prescriptions of our Mother the Church and follow them as best as our ability, and the grace of God, allows. No one should try to extend the life of the body at the expense of the soul.

Above all, we mustn’t trust our own judgment. We must be accountable to someone.

Trust in the Lord with all your heart; and lean not on your own understanding.[22]

As Orthodox Christians, we know that the actions of our bodies, such as bows, prostrations, and making the sign of the Cross have a relationship to the state of our soul before the True God. Why would we ever chance copying bodily actions that for centuries have been directly related to the worship of demons? Such actions could have serious consequences for both our soul and body which belong to Christ.

May we be wise as serpents and harmless as doves.[23]

For comments and questions please contact the author Joseph Magnus Frangipani at Joseph.Magnus9@gmail.com.