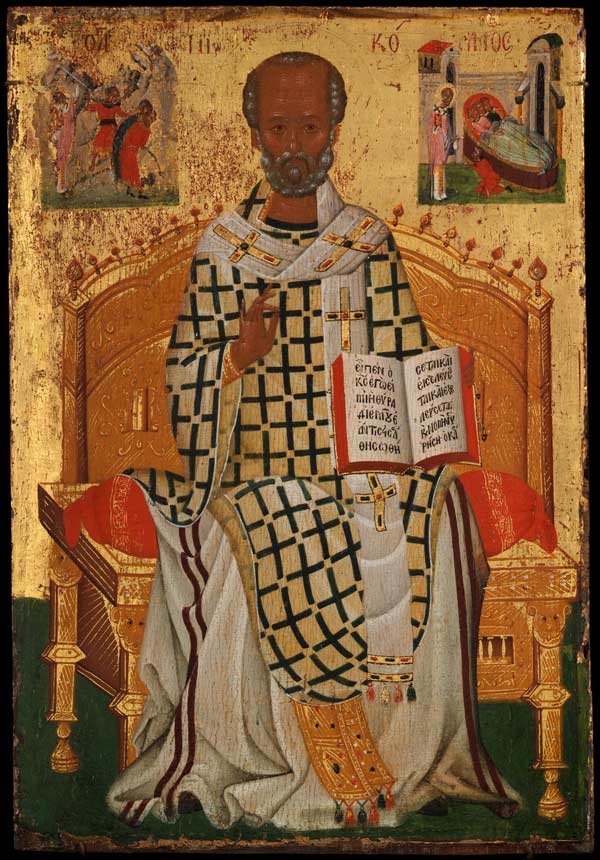

Saint Nicholas, from four icons from a pair of doors (panels), possibly part of a polyptych, early 15th century. Made in Crete? Byzantine. Tempera and gold on wood; 10 13/16 × 7 3/8 x 5/16 in. (27.4 x 18.8 × 0.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Mary and Michael Jaharis Gift, 2013 (2013.980d)

Saint Nicholas, from four icons from a pair of doors (panels), possibly part of a polyptych, early 15th century. Made in Crete? Byzantine. Tempera and gold on wood; 10 13/16 × 7 3/8 x 5/16 in. (27.4 x 18.8 × 0.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Mary and Michael Jaharis Gift, 2013 (2013.980d)

The exhibition Liturgical Textiles of the Post-Byzantine World, now on view through November 1, 2015, presents a selection of notable liturgical vestments that communicate the continuing prestige of the Orthodox Church and its clergy in the centuries following the fifteenth-century fall of Byzantine Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks. From a strictly theological viewpoint, vestments are hardly a necessity for Christian worship. Liturgical scholars are largely in agreement that for the first several centuries of Christianity's existence, its clergy officiated at services wearing the normal "street dress" of the Roman world. Only gradually did these items of clothing take on special significance as liturgical vestments, to be worn only during worship.

Tunic with Dionysian ornament, probably 5th century. Egypt, Akhmim (former Panopolis). Coptic. Linen, wool; plain weave, tapestry weave; L. 72 1/16 in. (183 cm) W. 53 1/8 in. (135 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Edward S. Harkness, 1926 (26.9.8)

Tunic with Dionysian ornament, probably 5th century. Egypt, Akhmim (former Panopolis). Coptic. Linen, wool; plain weave, tapestry weave; L. 72 1/16 in. (183 cm) W. 53 1/8 in. (135 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Edward S. Harkness, 1926 (26.9.8)

The history of liturgical vestments in the later centuries of the Byzantine Empire is one of increasing distinctions. Not only did vestments, as before, differentiate the clergy from the laity and distinguish orders within the clergy (bishops, priests, deacons, subdeacons, etc.), but new additions to the repertoire of vestments helped to distinguish rank within these clerical orders. Hence, from the eleventh century onward, metropolitans and other bishops of high rank were entitled to wear the polystavrion phelonion (as seen in Saint Nicholas above), a vestment decorated with an all-over pattern of crosses. Byzantine canonists' repeated insistence on the limited number of bishops entitled to this vestment is belied by its rapid spread over the twelfth through fourteenth centuries. Perhaps to compensate, a still more privileged vestment, the sakkos, was introduced in the twelfth century, to be worn only by patriarchs and archbishops on only the most important of feast days.

The introduction of figural embroidery on vestments, which likely occurred in Byzantium as a new phenomenon in the twelfth century, can be seen as part of this trend to differentiate the garments and insignia of the highest-ranking figures from those of lower ranks. This is not to say, of course, that the embroideries were merely a means of self-aggrandizement by the clergy; rather, they point beyond themselves to the mysteries of the liturgy as a dramatic reenactment of the life of Christ and a microcosm of the divine kingdom.

Hanging, 18th century. Armenia. Silk, gold, and silver; brocaded; L. 97 in. (246.4 cm), W. 92 in. (233.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Cornelius Bliss, 1942 (42.19)

Hanging, 18th century. Armenia. Silk, gold, and silver; brocaded; L. 97 in. (246.4 cm), W. 92 in. (233.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Cornelius Bliss, 1942 (42.19)

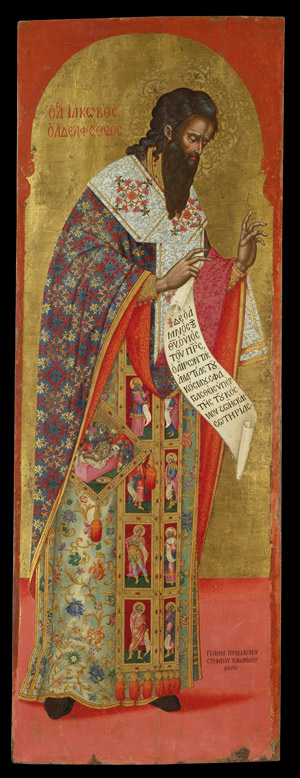

Stephanos Tzangarolas (active 1688–1710). Lateral sanctuary door with Saint James the Brother of the Lord, 1688. From the Church of the Holy Trinity on Corfu. 2.03 x .81 m. Benaki Museum, Athens. (ΓΕ 3012)

Stephanos Tzangarolas (active 1688–1710). Lateral sanctuary door with Saint James the Brother of the Lord, 1688. From the Church of the Holy Trinity on Corfu. 2.03 x .81 m. Benaki Museum, Athens. (ΓΕ 3012)

Although vestments of the late Byzantine period (1261–1453) were generally decorated with embroidery on plain, unpatterned silk textiles, the post-Byzantine period saw the rise of patterned silks intended specifically for liturgical use. These seem to have been a specialty of the imperial Ottoman textile workshops at Bursa and Istanbul, and records from Moscow attest to the importation of various patterns of woven silks—many with gold and silver threads—from Ottoman Turkey to Muscovy for use in the vestments of the clergy.

One such pattern, with the figure of Christ enthroned among the four symbols of the Evangelists, is known from vestments in the Kremlin in Moscow and can be viewed on a sakkos now in the collection of the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) Museum. Like the two Ottoman textiles featured in the exhibition (below, top left and top right), its figural motifs are surrounded by crosses with the abbreviations ΙϹ ΧϹ ΝΙΚΑ, for "Jesus Christ is victorious." These patterns thus continue to adhere, centuries later, to the custom that the vestments of the clergy of highest rank should be adorned with repeating patterns of crosses. Even the Russian embroidered yoke of a phelonion (below, bottom), the design of which borrows from the stock of ornamental motifs—vines, tulips, serrated saz leaves—common among Ottoman textiles, also includes golden crosses at the centers of the silver, palmette-shaped leaves.

Top left: Silk textile with seraphim and crosses, 16th–17th century. Turkey, Istanbul or Bursa. Islamic. Silk and metal-wrapped threads; lampas weave; H. 21 1/8 in. (53.7 cm), W. 24 5/8 in. (62.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1917 (17.22.2a–d). Top right: Silk textile with seraphim and crosses, 17th century. Ottoman Empire. Silk, lampas weave (ground in satin, pattern in twill); 43 x 22 1/2 in. (109.2 x 57.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1908 (08.109.16). Bottom: Yoke of a chasuble (phelonion), 17th century. Russia. Silk; embroidered in silk and metal thread with (later) metallic trim; H. 13 1/4 in. (33.7 cm), W. 32 1/4 in. (81.9 cm), D. 2 in. (with insert). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1917 (17.157)

Top left: Silk textile with seraphim and crosses, 16th–17th century. Turkey, Istanbul or Bursa. Islamic. Silk and metal-wrapped threads; lampas weave; H. 21 1/8 in. (53.7 cm), W. 24 5/8 in. (62.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1917 (17.22.2a–d). Top right: Silk textile with seraphim and crosses, 17th century. Ottoman Empire. Silk, lampas weave (ground in satin, pattern in twill); 43 x 22 1/2 in. (109.2 x 57.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1908 (08.109.16). Bottom: Yoke of a chasuble (phelonion), 17th century. Russia. Silk; embroidered in silk and metal thread with (later) metallic trim; H. 13 1/4 in. (33.7 cm), W. 32 1/4 in. (81.9 cm), D. 2 in. (with insert). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1917 (17.157)