Today, the best-known patron saint of England is the Great-martyr St. George the Victory-Bearer. However, the country has also its own native patron saint—Edmund the Martyr, King of East Anglia, one of the most venerated early Orthodox saints of the country to whom over 60 ancient churches were dedicated. Let us recall his life.

The early English kingdom of East Anglia was formed in about 520 AD. It corresponded to the present-day English counties Suffolk and Norfolk (and from the mid-seventh century—also eastern Cambridgeshire). Orthodox Christianity was introduced into East Anglia under King Raedwald who ruled from c. 599 till 624. The Christianization of this kingdom was carried out chiefly in the 630s and 640s and eventually this region became one of the most religious ones in the whole of England, with a host of monasteries, convents, churches and saints. Many of them are still remembered in local place names. Before St. Edmund, East Anglia produced two holy kings, both of whom were martyrs: Sigebert (+ c. 635) and Ethelbert (+ 794). The founders of the royal dynasty of East Anglia were the Wuffingas; however, after the martyrdom of Ethelbert this dynasty ceased to exist. As the ninth century was marked by the Danish raids on England which caused the destruction of many churches, archives and documents, it is not known exactly to which dynasty St. Edmund belonged. It is known that after 794, East Anglia was largely taken over by the powerful kingdom of Mercia, and then Wessex. However, it managed to survive. King Aethelweard of East Anglia died in c. 855 and Edmund, who presumably was his son, became his successor.

There is very little contemporary evidence on St. Edmund. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle in 890 writes that “in 870 the Danish Army went across Mercia into East Anglia and took winter quarters at Thetford, and the same winter St. Edmund fought against them and the Danes won the victory, they slew the king and took over the entire kingdom and destroyed all its monasteries.” He is also mentioned in the Life of Alfred the Great, written nearly at the same time by Bishop Asser, which reads that St. Edmund fought side by side with Alfred and was finally killed in battle. The first Life of Edmund was compiled by the Martyr Abbo of Fleury (c. 945-1004: feast: November 13) in about 986. Abbo spent two years (985-987) in England at the monastery in Ramsey, to which he had been invited. While he was in England, the saintly Archbishop Dunstan of Canterbury related to him the story of Edmund. Dunstan, a great authority, heard this story as a young man from King Athelstan, who had heard it from the old, personal sword-bearer of St. Edmund. The Latin Life of Abbo was translated several years later into old English by the learned English Abbot Aelfric of Eynsham (c.955-c.1020). This life survives to this day. There are also later and less reliable versions of life of St. Edmund, composed by Geoffrey of Wells in the twelfth century, Monk Robert Manning early in the fourteenth century, the monk and poet John Lydgate of Bury St. Edmunds (c.1370-c.1450), and others.

St. Edmund, whose name means “blessed protection”, was probably born in 841. He lived during one of the most troubled periods of early English history, when hordes of Danish pirates were devastating English kingdoms one after another, burning churches and monasteries, ravaging them, murdering Christians and all inhabitants. Such great monasteries as Coldingham, Wearmouth, Jarrow, Tynemouth, Whitby, Lindisfarne, Crowland, Bardney, Peterborough, Thorney, Ramsey, Soham, Barking, Chertsey and Reculver fell victim to the blood-thirsty Vikings at that time. According to tradition, Edmund was called to the throne of East Anglia by the kingdom’s people in this critical period. He landed from exile (according to one of the versions of his life) at St. Edmund’s Point near Hunstanton in Norfolk in 855, praying to God to give His blessing on him and his fellow countrymen. At Hunstanton he may have built a palace and ruins of St. Edmund’s Chapel there survive to this day. Then Edmund proceeded to the royal palace at Attleborough in Norfolk where he officially staked his claim to the throne. For a year young Edmund was instructed in Attleborough by Bishop Humbert of Elmham (who would also be martyred by the Danes). It was said that within one year he then learned all the Psalms of David by heart, and this Psalter was kept as a relic until the Reformation. The people saw in him their only hope to preserve their small Christian state. On the day of Nativity of Christ, December 25, 855 (or 856), the 15-year-old Edmund was crowned and anointed King of East Anglia. This may have taken place on the site of the present-day St. Stephen’s Chapel in Bures on the Suffolk-Essex border, which still stands in the Suffolk village of Bures St. Mary to this day. The following years showed that the people’s choice was providential: not only did Edmund become an exemplary and devout king, but he came to be a true national hero and a holy man.

Edmund was tall, with fair hair, well-built and with a particular majesty of bearing. He was a wise and honest man, pious and chaste in all his deeds. In all things he always strove to please God and by his pure life and glorious works he won the respect of all his subjects. Edmund was very meek and humble: he knew that, becoming a king, he could never be conceited with his countrymen, but should only be on a par with everybody in the kingdom. Edmund was protector of the Church and a shelter for orphans, was generous to the poor and cared for widows like a loving father. All who pleaded to him for justice received help. It was said that even children could walk alone great distances in the kingdom without any fear for themselves under St. Edmund. The holy king corrected the stubborn and impious and led his country to repentance. He served his nation so selflessly that he even refused marriage, laboring wholeheartedly for the good of the people. But all this was not to last long.

In 865, a huge army of Danes, known as “the great heathen army”, led by chieftain commanders Ingvar (identified as Ivar the Boneless) and his brother Ubba “who entered into alliance with satan,” attacked England, invading Northumbria, Mercia, East Anglia and Wessex. Burning and destroying everything on their way, the pagans decided to conquer the whole of England. According to tradition, Ubba lay waste to most of Northumbria, ransacking and plundering its territory, and remained there. This was in 867, and in the following year the Vikings seized Nottingham in Mercia. They attempted to attack East Anglia more than once, and Edmund, concentrating all his strength, arranged a lasting resistance to the invaders. The “Fortifications of St. Edmund” near Newmarket still mark the activity of the holy king in the region. It is obvious that Edmund even won several minor battles with the Danes but the pagan army was too numerous and strong (it may have had over 20,000 soldiers). Thus, in 869, like a rabid wolf, Ingvar ferociously flew across East Anglia, put to death many men, women and cruelly tortured defenseless Christians. Finally Thetford, the capital, was taken over and all its population slain. Only Edmund with a remainder of his army survived at this crucial moment.

Intoxicated with his success, Ingvar sent a menacing message to the king: If Edmund valued his life then he was to bow before him, Ingvar, as his vassal. The messenger ran up to the king and proudly exclaimed, “Ingvar, our powerful and mighty chieftain, won many victories on sea and land, conquering many peoples. He is ordering you to obey him and to give him all your treasures immediately. If you do not want to die, you must recognize him as your lord; and you are not strong enough to resist him anyway.” Edmund called for his bishop and asked for advice. The bishop, horrified by the sacking of the country and fearing for Edmund’s life, answered: “It is better to submit to Ingvar and become a sub-king under his rule.” And the saint replied: “O, bishop! My poor nation is humiliated and I would rather fall in battle with him who will stretch forth his hand against my people and their heritage.” But the bishop said, “Alas, dear king! Your people lie dead, and you have no strong army to struggle. The pirates will come and seize you, unless you escape or submit to their leader’s demands.” Edmund answered bravely, “You offer me the life of a slave, but I do not wish to save my life after my servants have been murdered together with their wives and children. I am not used to fleeing my enemies, and, if God wills, I am ready to give my life for my people and my faith. My Lord knows that I will never renounce His love and will never stop serving Him, even if I have to die.” Then Edmund addressed the messenger and pronounced, “Go and tell your master that King Edmund will never bow before the heathen chief Ingvar until he bows before Christ as the true God!” The messenger left and passed Edmund’s words to Ingvar. Hearing the bold reply of the king, he at once ordered his forces to find and seize Edmund who ventured not to obey him.

The martyrdom of St. Edmund followed on November 20 / December 3, 869 (early sources give 870, but most modern research agrees on 869 as the authentic date).

St. Edmund stood praying hard in his royal hall, imploring the Savior to strengthen him in this difficult hour. He only thought how to stop the bloodshed and to preserve his Christian country. Shortly before the arrival of the wicked men, Edmund said to Humbert, “O father bishop! It is necessary that I alone should die for my countrymen, lest the entire nation should perish.” Seeing the multitude of pagans, Edmund dropped his weapon, imitating Christ Who refused to defend Himself in the Garden of Gethsemane. The Vikings bound Edmund hand and foot and then subjected him to relentless tortures and beat him with thick sticks. After that the murderers tied Edmund to an oak tree and for a long time flogged the king with whips, constantly insulting him. The humble and faithful king bore all the suffering with great patience and only kept pronouncing the name of Jesus Christ. The heathen were filled with fury, hearing the name of Christian God. They then shot arrows at the holy martyr until he was covered with them, in his passion repeating the exploit of St. Sebastian. At last, Ingvar realized that the pious king would never renounce Christ and commanded his servants to behead him. The soldiers instantly fulfilled his command, and St. Edmund until the last moment of his life repeated and called on the name of Christ Who was above all for him. Edmund was twenty-eight; he had ruled his kingdom for fourteen years. One man who was concealed by Divine Providence from the pirates witnessed all that happened to St. Edmund, and later related the story as it was recounted by St. Dunstan to St. Abbo. The savages returned to their ships, before their departure throwing the severed head of the martyr into a dense thicket of brambles.

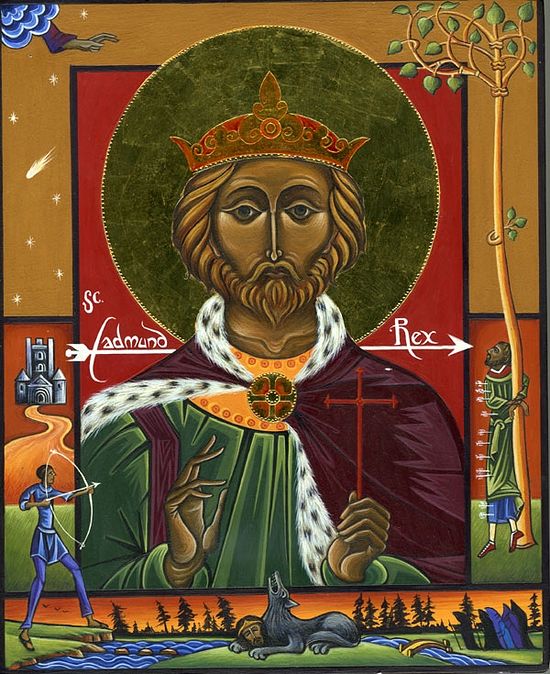

Soon frightened Christians came to the scene and wept at the death of their dear lord for a long time. Then they wanted to bury him as a Christian but could not find his head. With much sorrow and tears they started searching in the surrounding area. They cried, as if he were alive: “Where are you? Where are you?” And suddenly they heard the voice: “I am here, I am here!” The amazed people rushed on the voice and soon found what they were looking for. And it is difficult to describe their astonishment when the Christians saw that the king’s intact head was being guarded by a large wolf (probably the tame wolfhound of Edmund). The head lay between its paws, and the wolf was gently and carefully protecting it from wild animals, sensing the holiness of this man. The faithful took the head and solemnly carried it along with the martyr’s body to the town. The wolf walked all the way behind them, and when the procession reached the town it obediently turned back to the forest. Since that time painters have depicted on icons this scene with the wolf guarding Edmund’s head. The king’s body was buried with great honor, and since that time he has been venerated as a martyr and genuine national hero, who sacrificed his life for Orthodoxy and for his kingdom and people. When the raids of the Danes ceased, a chapel was built above the grave of St. Edmund. Miracles began to occur near his tomb, and a column of unearthly light was seen by many above that site. Meanwhile, veneration for Edmund spread all over England, and, most strikingly, many Danes living in the Danelaw (parts of northern, eastern and central England where Danish laws and customs were observed from the late ninth century until the Norman Conquest) repented, began to venerate Edmund as a saint, believed in Christ and took Baptism. In the Danelaw the Danes even started to produce commemorative coins of St. Edmund. Many of these coins have been discovered in East Anglia over the past two centuries. Thus Edmund through his self-sacrifice contributed much to the national unity of the English and brought many Vikings to the true faith, continuing his service and mission after his death.

Let us now speak a little about the place of martyrdom of St. Edmund. St. Abbo calls this site “Haegilisdun”, and mentions that his head was hidden in the forest with the same name nearby. Hermanus of Bury St. Edmunds says that the site of his first burial was called “Suthtuna”. None of these place-names have survived, and there are many potential candidates as the location of the saint’s martyrdom. Though there is no written evidence to support it, traditionally the village of Hoxne in Suffolk is considered by most academics and local people to be this exact site. Traditions connected with St. Edmund abound in this village, which has a special atmosphere. There existed two early medieval chapels in honor of St. Edmund in Hoxne from the earliest period where the martyr was highly venerated. Presumably his relics rested in one of them (one stood in the village and the other one in the forest nearby) and early in the tenth century they were translated to a new church built for this purpose. There existed an early diocese in Hoxne with the bishop’s residence, and it is believed that today’s vicarage behind the church, surrounded by a wide moat, marks the site of the original bishop’s palace. The Benedictine Priory existed in Hoxne from the thirteenth century until the Reformation (attached to the important Norwich Priory) with St. Edmund’s chapel as its center. A healing spring of St. Edmund long existed in this village near the site of his supposed martyrdom and its water healed many cripples. Most remarkably, there was an oak tree identified with the tree to which St. Edmund had been tied by Danes. This very tree stood in Hoxne until 1848, that is, 1000 years since the martyrdom, and, when it fell, the heads of two Danish arrows were found imbedded into it—thus the tradition about St. Edmund was more or less confirmed by this miraculous event.

As for “Suthtuna”, one theoretical candidate for it is “Sutton Hoo”, a very early site with graveyards near Woodbridge in Suffolk. Other speculative candidates for the site of Edmund’s martyrdom have been Hellesdon near Norwich in Norfolk, Bradfield St. Clare near Bury St. Edmunds in Suffolk, Hollesley near Woodbridge in southeast Suffolk, the villages of Wissett and Old Newton in Suffolk, and Hazeleigh near Maldon in Essex. All of these or places near them had name forms similar to “Haegilisdun”, with either appropriate forests or fields nearby, but that is all; none of these places has an early (or even any) tradition associated with St. Edmund. Hoxne, however, has a rich tradition; but the name of “Haegilisdun” was not recorded. Such modern authors as Margaret Carey Evans of Hoxne helped determine the location of the two chapels of St. Edmund in Hoxne and confirm his close link with this village. Moreover, people in recent times have again seen the column of supernatural light in the vicinity of Hoxne.

Now let us return to the veneration of St. Edmund. Over thirty years after St. Edmund’s death passed, and it was decided to build a large church near his grave. When his relics were uncovered, many believers became eyewitnesses of a great miracle: the saint’s body lay completely incorrupt, his formerly severed head was attached to the neck, and all the wounds from arrows were healed. The saint looked as if he were sleeping. Everybody thanked God for His mercy and translated the saint’s relics to the church. Early in the tenth century, a church with a community of priests was erected in the town of Beodericsworth in Suffolk where his relics were kept from that time. This town, in which the first monastery had been founded by St. Sigebert as early as 631, was renamed St. Edmundsbury after St. Edmund, and later obtained its present name—Bury St. Edmunds. Kings Edward the Elder and Athelstan encouraged his veneration, and early in the eleventh century a monastery in honor of St. Edmund was founded there, and King Canute (1017-1035) donated lands and freed the abbey from any diocesan control, and so from that time the town and monastery were direct dependencies of Rome. Construction of the huge Roman Catholic abbey on the same site began in the second half of the same century under its third abbot, and the saint’s relics were solemnly translated to the new decorated shrine in 1095. The relics were kept behind the high altar.

Here are just a few miracles of St. Edmund. A certain widow called Oswyn lived near the tomb of Edmund and prayed and fasted there for many years. Every year she reverently cut the hair of the saint and trimmed his nails (which continued to grow) and placed these relics in a separate shrine near the altar. One night eight thieves decided to steal the treasures which people used to bring to the St. Edmund’s Church. They thoroughly planned how they would do it. One of them was to strike the bars with his hammer, another one was to use a file, another was to dig under the entrance with a spade, another was to unlock the window with a ladder. But all their efforts were in vain as St. Edmund through his prayers bound them invisibly so that each of them suddenly became immovable at the scene of their night crime. Thus they stood till the morning. When people came, they saw one of them hanging on the ladder, another stooped at digging, and others stiffened in filing and hammering! The robbers were immediately submitted to the bishop and received their punishment.

There was a wealthy man named Leofstan who was ignorant of God. He rode to St. Edmund with arrogance, ordering that the saint’s body be shown to him so that he might check if it was whole. But as soon as he saw the relics Leofstan went mad and some time later died a wretched death.

During the reign of Edward the Elder (899-924) a blind man with a boy who accompanied him walked in the forest near Hoxne. Not seeing any house for shelter for the night, they decided to stop in what was the first wooden chapel with the relics of St. Edmund. On entering they stumbled on the king’s grave. Terrified, they decided to stay there all the same and use the grave as their pillow. As soon as they closed their eyes, the Divine light filled the chapel. The boy woke the blind man up in fear, but it turned out that the man’s sight was restored by the grace of the saint’s presence. Learning about the miracle, the faithful resolved to translate the martyr’s remains to a more fitting place.

In 1010, Edmund appeared in a vision to a priest named Ethelwine and commanded that his relics be taken to London to escape the Vikings’ raids. While in London, eighteen people were cured of various maladies from the relics near St. Paul’s Cathedral, and one woman was healed of paralysis—and all this on the same day. Later a Danish man was cured from blindness when the relics rested at St. Gregory’s Church in London. And on the way back to Bury, the host of a manor was healed from a chronic illness for his hospitality to the priests who were carrying the relics.

St. Abbo concludes his Life of Edmund with the following words: “The English land is not deprived of saints of God as long as in its soil lie such great saints as this holy king, and blessed Cuthbert, and Etheldreda (Audrey) at Ely and her sister Withburga—all of them sound in body, confirming the true Orthodox faith.”

From the ninth till the fourteenth centuries, St. Edmund was officially venerated as the patron saint of all England, and his veneration spread to many other European countries (Edmund is still a popular baptismal name throughout much of Western Europe). In the Middle Ages, Bury St. Edmunds Abbey was one of the largest, richest and most powerful in England; indeed it was one of the largest Romanesque churches in Europe. The whole territory of west Suffolk, known as “the Liberty of St. Edmund”, belonged to the monastery, which was like a lavra in its significance. Only Canterbury and Walsingham rivalled Bury (the common name for the town) in popularity. Many facts of the abbey’s life are known due to the Monk Jocelin, who wrote its chronicle. The abbey was cruciform; it was over 500 feet long and 246 feet wide. Its library was counted as one of the intellectual centers of Europe and numbered thousands of volumes. The abbey had a scriptorium; its monks studied the Bible, works of Holy Fathers, made fine works of art, literature and theology. There were three breweries within the abbey. The abbey resembled a whole city. The monastery annually distributed a quarter of its income to poor residents of “the Liberty of Edmund”, gave food and alms to the needy at the abbey gate every day, and accommodated even the poorest guests at its guesthouses.

Bury had a very turbulent history. Of course, it prospered as a center of pilgrimage, holiness and learning, but it was severely damaged more than once during the revolts of the townspeople, especially in 1327. In 1214 the barons gathered at Bury near St. Edmund’s relics and swore to force King John Lackland to sign the Charter of Liberties. It was a historic moment, and the king indeed signed the “Magna Carta” the following year. Two important fairs started in Bury in the fourteenth century, and one of them still goes on. Unfortunately, the holy relics of St. Edmund were stolen by invading French knights in 1217 and taken to Toulouse, where they were much venerated at the Basilica of St. Sernin for many years, with numerous miracles reported. Only in 1901 were his relics returned to England. At first it was planned to place them in the Catholic Westminster Cathedral in London. However, at that time it was impossible to prove the authenticity of the relics of the saint with certainty, so they were placed in the private chapel of Arundel Castle in West Sussex under the care of the Duke of Norfolk, where they remain to this day and are not accessible for veneration. There is an ancient prophecy that one day his holy relics will return to Bury St. Edmunds, and this event will mark the spiritual regeneration of the English nation.

Under King Edward III (1327-1377) who established the Order of the Garter and made the Mother of God and St. George the Victory-Bearer its protectors, the veneration of St. Edmund as the patron-saint of England lessened. St. George became the new patron-saint of England (since c.1343), a symbol of its military might, the crusaders and knights. Now there are campaigns in England to make St. Edmund the principal patron-saint of the country again, and he is already the official patron-saint of Suffolk, where his flag flies.

Bury St. Edmunds Abbey was dissolved together with other monasteries in about 1539. Many former abbeys became cathedrals after the dissolution, but not Bury. The formerly magnificent monastery fell into ruin, and for many years people used its materials as a quarry for stone; now only tall rubble ruins of the former monastery survive. Bury Abbey had at least three enormous monastic churches: St. James, St. Mary and St. Margaret. St. Margaret is already gone (only its one wall and vault remain), but two others stand to this day. The former St. James Church, which was rebuilt early in the sixteenth century, was made a Cathedral in 1914. For more than forty years the church architect Stephen Dykes Bower (1903-1994) refurbished and partly rebuilt this church so that it might look and serve as a real Cathedral. Indeed millions of pounds were spent on this project of restoring the new cathedral church and its tall neo-gothic tower, which today look quite breathtaking. The Cathedral has a St. Edmund’s art exhibition and a painting of his martyrdom hangs in its Lady Chapel (a work by the modern Irish painter Brian Whelan). The second church is St. Mary’s, restored in the nineteenth century. It is one of the largest parish churches in England and is the burial place of Princess Mary Tudor, sister of King Henry VIII, who was briefly a wife of the King of France and died in 1533 at the age of 37. The abbey ruins, open to the public, are situated in the town center in the park amid beautiful gardens. A sense of holiness still lingers there. One even can identify the exact location of the saint’s shrine among the ruins. A few researchers believe that the relics of St. Edmund were not stolen by French soldiers in 1217, and that they, along with those of Sts. Jurmin of East Anglia and Botolph of Iken, still may rest in the grounds among these picturesque ruins and will be discovered there one day when God provides. Among today’s ruins the scriptorium, chapter house, north transept, nave, sanctuary can clearly be identified; the abbey crypt was dug out from the ground together with remains of its chapel after the Second World War. One of the abbey walls still survives intact, together with its two gatehouses (one of them is used as entrance to the park and another one is used to house the Cathedral bells). The nineteenth century Catholic Church of St. Edmund is situated in this town as well, and this church has a very small portion of St. Edmund’s relics. This town is still visited by pilgrims.

The charming village of Hoxne is visited by Orthodox and other Christians. The local fourteenth century Church of Sts. Peter and Paul has many ancient monuments, some of them connected with the saint, and tells the story of St. Edmund and the history of the village. In the middle of the village field stands the memorial cross in honor of St. Edmund—on the same site where the oak tree to which (presumably) St. Edmund was tied by pirates had stood for 1000 years. This holy spot is also visited by the faithful who pray there and feel a special atmosphere and the presence of Edmund. A monument to St. Edmund stands on the gable of the nineteenth century village hall of St. Edmund. The local Goldbrook bridge across the tiny river Goldbrook boasts a whole legend associated with St. Edmund, which is depicted in a plaque outside the village hall. According to local folklore, when the pagans were chasing the king, he took refuge under this bridge. At that time a newlywed couple walked over it. The couple spotted the gleam of Edmund’s golden spurs, reflected in the water and betrayed the king to the soldiers. From that time it has been believed that no newlyweds should cross this bridge on the day of their wedding—otherwise the marriage will fail.

Another important site connected with St. Edmund is Greensted-juxta-Ongar in Essex. This spot today is even less than a village as it consists of only a few houses. This place, however, is visited by thousands of pilgrims every year because it has a church, which is the oldest surviving wooden church in the world (and one of the oldest surviving wooden religious buildings in the world). It is dedicated to St. Andrew the Apostle; and it was here that St. Edmund’s relics were kept for a short time in about 1013. As was mentioned above, there was a constant risk of new Vikings raids on England, and so the relics of Edmund were moved from Bury to London. There they were greatly venerated for three years, and in memory of their presence in the capital the outstanding architect Sir Christopher Wren (1632-1723) built a fine Church of St. Edmund in London between 1670 and 1680 on the site of an earlier one, which stands to this day in Lombard Street but holds no regular services. On the way back to Bury the procession with relics made stops at Edmonton (now a district of London named after Edmund) and Greensted, where the same church that we can see now stood there. Though it was partly rebuilt, the oldest parts of its nave are from the ninth and tenth centuries, and several beams may date to the sixth to seventh centuries. It is supposed that the trees from which this church was built grew at the time of Jesus Christ! This church is a rare, unique surviving structure and preserves a very warm spirit both inside and outside.

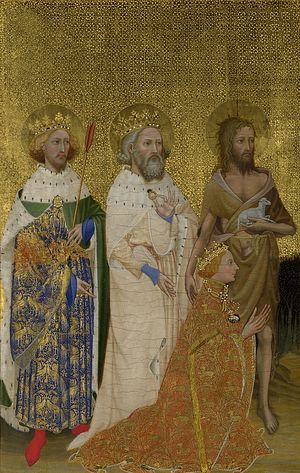

Today many dozens of Anglican and Catholic churches across England are dedicated to St. Edmund, especially in Suffolk and Norfolk—many of them are described by the modern photographer and researcher of churches Simon Knott on his most interesting “Suffolk churches”, “Norfolk churches” and “Essex churches” online projects. St. Edmund is depicted on stained glass windows and in wall-paintings of numerous English churches, many churches have statues of him—for example, Salisbury Cathedral, and a number of English colleges are named after him. In the Middle Ages Englishmen created splendid artistic masterpieces in honor of the saint; one of them is the fourteenth-century Wilton Diptych on which St. Edmund is depicted together with Edward the Confessor, St. John the Baptist, and King Henry II (now in London’s National Gallery). On icons he is often depicted as a king, usually crowned and with scepter and orb, frequently with an arrow, a sword or a wolf. The so-called “Flag of St. Edmund” consists of three gold crowns on a blue background. The flag of East Anglia (today the name of a region embracing Suffolk, Norfolk, parts of Essex and Cambridgeshire) is a combination of the red St. George’s cross of England on a white background and that of St. Edmund’s and the Wuffingas Dynasty (three crowns in the blue field). Arrows, three crowns—the attributes of Edmund, together with the former kingdom’s flag—can be seen here and there in a host of places across Suffolk and Norfolk to this day. There is a modern Orthodox service to St. Edmund in English, and, in addition to this, old hymns and fragments of early services to the saint still survive.

Today many Orthodox Christians in England hope that St. Edmund will work a new miracle; that his relics will become available for general veneration, and all who need the prayers of the holy king and martyr will be able to ask for his intercession in this holy place.

* * *

Among churches dedicated to St. Edmund nowadays we can mention the following ones situated in: Emneth in Norfolk (the large church dates to the twelfth century, there are ancient figures of angels, apostles, stained glass, and examples of medieval painting); Castleton in Derbyshire (the church is Norman, and has many architectural styles and stained glass); Hardingstone in Northamptonshire (twelfth century); Hauxton in Cambridgeshire (fifteenth century); Kingsbridge in Devon (in the Perpendicular style); Fritton in Norfolk (contains scenes from the saint’s life; it has a round tower as do very many Norfolk churches); Taverham in Norfolk (some of its parts are from the Saxon period); the medieval church at Costessey in Norfolk; Southwold in Suffolk (built in the fifteenth century, one of the best churches in Suffolk); Assington, Hargrave, Kessingland (fifteenth century. The tower is 300 feet high) and in the pretty little village of Bromeswell near Woodbridge in Suffolk; in Holme Pierrepont in Nottinghamshire; Wootton on the Isle of Wight (built in 1087); the Church of the Holy Trinity and St. Edmund in the city of Bristol; the Roman Catholic church in Halesworth in Suffolk; the Roman Catholic church in Withermarsh Green in Suffolk; the charming church in Burlingham in Norfolk; Caistor St. Edmund on the site of a Roman town in Norfolk; Downham Market, Forncett End, and many other sites in Norfolk; Ingatestone in Essex, and so on. St. Edmund the Martyr should not be confused with the Catholic saint Edmund Rich, or Edmund of Abingdon (c.1175-1240) who was Archbishop of Canterbury and to whom some churches are also dedicated.

Holy King Edmund, patron saint of England, pray to God for us!