SOURCE: New English Review

By Hal Smith

According to Oleg Usenkov, press secretary of the Sophia association of Russian Orthodox Christians in the Holy Land, there are about 70,000-100,000 Russian Orthodox Israelis, and perhaps “the real figures are even higher.”1The number is significant, as the “Greek Orthodox Patriarchy of Jerusalem was informed by the Ministry of Immigrant Absorption that approximately 10 percent of the total Aliya from the former Soviet Union are of the Christian Orthodox faith.”2 This makes the Orthodox Church by far the largest among the past several decades of Israeli immigrants.3 It is also the largest among Palestinian Christians, of whom there are about 400,000 worldwide, and through whom it traces itself to the first Christian community.4

Over the same period as the immigration, a controversy has grown among scholars in the western world portraying Christian traditions as “Supersessionist.” This indirectly places Orthodox Christians at the unintended center of a discussion affecting how they are viewed.5 Considering the role they play in bridging three major cultures, it is helpful to consider their beliefs in a way that can improve the interfaith relations those scholars seek.

Faced with a range of definitions on “Supersessionism” and the relative silence of Orthodox writers mentioning it directly, one must turn to a more basic understanding of the word “supersede” and its rare use by Orthodox writers. The topic of Supersessionism can be a coin with two sides: however hard that may be to understand, it appears to the author that Orthodox teaching on the Old Testament is Supersessionist, but not in every way. Bound up in the western scholars’ inquiries is often the issue of anti-Semitism, which some allege is inherent in Supersessionism. In fact, the Church has spoken out against anti-Semitism and what Supersessionism Orthodoxy may have ultimately does not support it.

Defining “Supersessionism”

Dr. Michael Vlach, an Evangelical scholar, defines Supersessionism as “the view that the New Testament Church supersedes, replaces, or fulfills the nation Israel’s place and role in the plan of God.”6 He emphasizes that “supersessionism… can encompass the concepts of ‘replace’ or ‘fulfill.’”7 A difficulty with this description is that “replace,” “fulfill,” and “supersede” each have significantly different meanings and connotations. As a result Vlach notes that some Christians would use the word “fulfill” but not “replace.”8

While Vlach sees “replacement” as a possible part of Supersessionism, the online Christian Encyclopedia Theopedia does not, saying:

Supersessionism is the traditional Christian belief that Christianity is the fulfillment of Biblical Judaism, and therefore that Jews who deny that Jesus is the Jewish Messiah fall short of their calling as God's Chosen people... The traditional form of supersessionism does not theorize a replacement; instead it argues that Israel has been superseded only in the sense that the Church has been entrusted with the fulfillment of the promises of which Jewish Israel is the trustee.9

In The Mis-Education of a Young Evangelical, from the United Church of Christ, Dexter Van Zile considers Supersessionism to be “the notion that Christianity has replaced the Jews.” He writes that some Christian Zionists “merely take Scripture at face value, reject supersessionism… and proclaim that God’s promises to the Jews are, like His promise to Christians, trustworthy and reliable.”10 Van Zile is pointing to a main difference between Protestant and Orthodox Biblical interpretation: the latter focuses more on maintaining the views passed down since early Christianity. Both groups in reality look for the plain reading (“face value”) and consider texts in light of their respective traditions.

Dr. Thomas A. Idinopulos, Director of Jewish Studies at Miami University in Ohio, was raised Greek Orthodox and appeared to develop a more Protestant orientation.11 In his book Betrayal of Spirit, Idinopulos agrees with Clark Williamson’s criticisms of Supersessionism:

What is the basic Christian theological anti-Judaic teaching of contempt? Williamson's answer is Supersessionism: that the revelation of God in Jesus Christ surpassed and therefore canceled the on-going validity of revelation of God to the Biblical people of Israel. Supersessionism, in all its variations, is seen in the church's valuation of the New Testament over the Old Testament (beginning with those very terms, "New" and "Old"). Supersessionism is conveyed by the church's sense of triumph as the newly elected people of God, a new covenant, replacing the old covenant (Israel). Supersessionism values the Hebrew Scriptures only as the prophetic preparation of the revelation of Jesus as the Christ. The teaching of contempt is forcefully conveyed in the message that Israel is judged, found guilty, and was eternally punished for rejecting her own messianic King, Jesus proclaimed the Christ (Messiah).12

Idinopulos immediately added however, that Christian Zionism is not incompatible with Supersessionism: “Today, Supersessionism is seen in the posture of American Protestant Evangelical Church leaders, like Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson, whose right-wing politics allow them to champion the State of Israel while at the same time preaching a brand of eschatological Christianity which effectively negates Judaism.”13 If scholars like Idinopulos see such Evangelical postures as today’s Supersessionism, it may be that the concept of Supersessionism is perceived and re-interpreted by western scholars through the lense of modern Protestant formulations on Judaism. Namely, Protestant thinking may more legalistic, negating, and total with concepts like “Total Depravity”14 that were unknown to Orthodox Christianity and ancient Judaism (and remain so). Then, when faced with polemics by early Christians, scholars interpret them in the more absolute terms used in modern portrayals of Supersessionism.

Regardless of whether Idinopulos was looking at things in a Protestant way, many of his descriptions of Supersessionism’s negative effects are far too absolute for Orthodoxy. The Hebrew Scriptures are more than a preparationfor Christ, since they continue to provide moral instruction (2 Timothy 3:16-17), although it is read in light of the New Testament. Orthodoxy points to Old Testament righteous as saints for emulation. Second, how could Israel be “eternally punished” when St. John Chrysostom, one of the most polemical Church fathers, commented about those of them who rejected Christianity: “they will not perish forever,”15 pointing to St. Paul’s expectation of their embrace?

As to the meaning of the phrases “Old Testament” and “New Testament”, a wide range of meanings has been suggested. Nonetheless, the real meaning must be that which Paul gave the former in 2 Cor. 3:14, saying Christ took away the veil from “the reading of the old testament” by showing its prophetic meaning. Likewise, Jeremiah prophesied a future “new covenant” in Jer. 31:31, a phrase Christ used to refer to His “covenant” with Christians (Lk 22:20, 1 Cor 11:25; Heb 8:8). If one determines that these phrases are Supersessionist, he/she need go no farther to determine that Christianity is as well.

In any case, the definitions of Supersessionism are varied. Vlach sees it as encompassing replacement or fulfillment of Israel, Theopedia’s editors see it as fulfillment but not replacement of Judaism, Van Zile sees it as a replacement of Jews, and Idinopulos sees it as surpassing and canceling the validity of God’s revelation to the people of Israel. The only common element in these definitions is the idea of “supersession” itself, a word which may in some cases include replacement, and whose effects may vary greatly.

Two sides of the word “Supersede”

A boy tells his uncle: “I can move the water in your large pond all by myself.” His uncle asks “Where to? How?” The nephew responds: “Where it is how: I will just stir it.”

While a person may normally assume the word “move” means to shift something to another location, it can also mean to move something around in one space. The English language has many words that can have more than one related meaning, and in practice “supersede” turns out to be one of them.

The word came from 15th-17th century Scottish, where it meant “postpone, defer,… displace,” or “replace.”16 In Scottish law it especially referred to “a judicial order protecting a debtor.”17 The legal meaning of staying a judgment passed into English, where for example “supersedeas” is a “writ to stay legal proceedings,” meaning in “Latin, literally ‘you shall desist.’”18 Thus, the word has a particularly legalistic connotation, reflecting that Latin is a common origin for English legal terminology.

The root meaning of “supersede” in Latin is “supersedere to be superior to, to refrain from,”19 literally “sit” (-sedere) “over” (super-). The full range over meanings is: "To set above; to pass over, and prefer another to the prejudice of; to come in the place of; to take the place of; to make void, inefficacious, or useless by superior power; to overrule; to set aside; to suspend.”20 For example, a law could demand a punishment, but a merciful king could “supersede” it with a pardon, without removing the law itself from the kingdom’s statue-books.

To give an example of the use of the word by an Orthodox writer, Fr. Anatoliy Bandura of Holy Cross St Nektarios Greek Orthodox Church comments that according to almost all Eastern Church Fathers, by descending into Sheol (place of the dead) after the Crucifixion, Christ offered salvation to all there,

‘whether Jews or Greeks, righteous or unrighteous.’ If we accept the point of view of those Western Church writers who maintain that Christ delivered only the Old Testament righteous [in His Descent], then Christ’s salutary action is reduced merely to the restoration of justice. However, Orthodox theology goes further and asserts that God will save us in a ‘scandalous’ way because God’s justice supersedes human logic and understanding.21

In other words, while human logic thinks in terms of justice and saving only the righteous, God’s own justice supersedes, is superior to, and is preferred by Him over human logic, which of course exists as well. While not saying that Christianity supersedes the Old Testament per se, this passage reflects the Christian theme whereby Christ’s redemption (here: God’s justice) is considered to “supersede,” or take precedence over, another concept of “justice” or “Law.”

A common argument against using the term “supersede” in Christianity is that it would suggest that the older thing would be completely separate, destroyed, and made irrelevant in every sense. In fact, this is not necessarily the case when one thing supersedes another: a person’s body could “sit on” a chair (two separate things), but it could also “sit on” its feet (a whole vs. a part of the whole). An oil painter may start with a sketch and “supersede” it with layers of paint, yet the sketch survives in the form of the outline.

The author of a collection of Einstein’s quotations writes: "I've deleted some unverifiable, questionable [quotes] or placed them in the 'Attributed to Einstein' section. This edition therefore supersedes the quotations and sources of the previous editions.”22 Thus, even if some of a collection’s quotations are deleted or moved to a different section, the vast majority of quotations may remain.

Likewise, a caretaker can make an agreement (covenant) to maintain his neighbor’s house for a fee. Later, they make a short agreement saying only that the caretaker no longer has to clean the attic. The new agreement supersedes the old one, but the old one is still in force, although not all its requirements are followed.23 A similar logic can work for a reorganized community, which, like a renovated charity with a somewhat altered name and bylaws, can supersede another without the latter coming to an end.24

In fact, the word “supersession” in a religious context means that Christianity must accept Judaism into itself in important ways, since the major English poet Percy Bysshe Shelley wrote:

the mythology and institutions of the Celtic conquerors of the Roman Empire outlived the darkness… connected with their growth and victory… The incorporation of the Celtic nations with the exhausted population of the south impressed upon it the figure of the poetry existing in their mythology and institutions… it may be assumed as a maxim that no nation or religion can supersede any other without incorporating into itself a portion of that which it supersedes.

That is, Shelly sees ancient Celtic customs surviving the Dark Ages, despite the fact that the Celts accepted Roman-style institutions and became “civilized.”25 Naturally, the amount of the necessary incorporation may vary. Conceivably, a new stage of religious development could fully incorporate its predecessor.

Another argument against using the idea of the New Testament “superseding” the old one is that it would supposedly mean that those who reject the new covenant would be completely forgotten. It would contradict St. Paul’s discussion of those who rejected the new covenant, which compared them to branches broken from their olive tree (Rom 11:16-26). Despite their loss, St. Paul expected that they would return and be grafted in again.

However, the term “supersede” does not exclude the expectation of a return. A king could issue an edict that his subjects no longer have to pay a “bread tax,” superseding an earlier law whereby only farmers escaped the tax. Some farmers may disagree with the new edict and emigrate, yet the king could still expect their return, due to his love for them. And should they return, the same benefits of his edict could cover them. So simply because someone leaves a group wherein a change is made does not mean they are forgotten or that their return is not expected.

Orthodoxy as outside the debate on Supersession

Faced with the extreme scarcity of use of the term in Orthodox writings, one may consider that the concept itself is unknown to Orthodoxy. Vlach himself calls Supersessionism a “recent” designation,26 and thus the term is not in the tradition modern Orthodox writings draw from. Michael Forrest, a Catholic scholar, writes that “Supersessionism… has no established, Catholic definition. Not unlike ‘proselytism,’ it's a loaded term that can and does carry very different connotations, implications and nuances.”27

Greek and the Slavic languages, which a large majority of Orthodox speak, do not contain an exact equivalent of the word “supersede” with its nuances, and practically never use the word “Supersessionism.” Granted, people can express a concept without giving it a label that those of another culture may place on it. To give an analogy to the question raised by their lack of the word “supersede”: Could westerners perfectly sum up the complexities of the “soul” of classical 19th century Russian literature with a uniquely “western” word?

The second obstacle is not really linguistic, but conceptual. Considering the legalistic connotations of “supersede,” “Supersessionism” has a particularly legalistic understanding of the relationships between the two covenants. Thus, Factopedia’s entry on Supersessionism comments on this difficulty:

Eastern Orthodox… groups… focus on the work of the Holy Spirit in defining church membership. It has long been noted by theologians that pursuit of a dynamic, experiential and personal experience of faith has been typical of eastern theology, where legal and logical formulations have dominated in the Western churches… [T]he focus on personal spirituality rather than intellectual assent means detailed analysis of covenantal issues is considerably less a feature of these traditions.28

Herman Blaydoe, a church cantor who studied at Christ the Saviour Seminary, goes further and sees Orthodoxy as outside ideological categories (“-isms”):

"Orthodoxy" does not "match" any version of supersessionism. We don't do or need any "ism". The Church is bigger than any "ism". Just about any word with an "ism" suffix is probably next to useless in any discussion of the teachings of Orthodoxy. It is extraneous, it isn't really Patristic. We do not need to rehabilitate bad Protestant theology.29

This brings to mind the difficulty with using the loaded term “proselytism” that Catholic scholar Michael Forrest pointed out.30 On the other hand, “Judaism” is a central idea throughout this discussion, and the Church engages in “Evangelism.” So while “-isms” can enter the discussion, Orthodox are usually reluctant to talk in terms of new ones.

All of this may serve as a cautionary note: should “Supersessionism” exist in Orthodoxy, it may not play as central a role or be formulated in the way others describe it.

Heads: How Orthodoxy is “Supersessionist”

Notwithstanding the above, it appears Supersessionism is one “side” of Orthodox thought. Orthodox materials occasionally use the word “supersede” to describe the Church’s beliefs in different ways. The Orthodox Study Bibleuses it in the sense of a transformation. It translates the prophecy of Isaiah 28:4-6 thus:

the flower that fell from the hope of the glory on the top of the high mountain shall be like the forerunner of the fig. He who sees it wishes to swallow it before he gets it in his hand. In that day, the Lord of hosts shall be the crown of hope, woven of glory, to the remnant of My people. They shall be left in a spirit of judgment upon judgment and for the strength of those who prevent slaying.

Perhaps one may compare the “high mountain” to Mount Sinai, and the flower that comes down from it to the Covenant with Moses. The “flower” is not destroyed, but rather transformed into a delicious fig that attracts people to it. It is associated with “judging judgment,” which accord with Fr. Bandura’s discussion above on God’s justice being higher than man’s sense of it. The people’s new spirit is also associated with preventing killing, that is, enacting mercy. The Orthodox Study Bible sees in this image basic elements of Christ’s relationship to the law, commenting: “Just as the fig replaces the fading flower, Christ will supersede the fading law and become the crown of hope, woven of glory.”31

The Orthodox Study Bible relates this supersession to the Temple sacrificial system and the Eucharist:

On the Day of Atonement, the preeminent Old Testament sacrifice was made. It was to atone for all the sins the nation of Israel had committed that year (Lv 16:2-34)... This event prefigures the once-for-all self-sacrifice of Christ, our great High Priest (Heb 4-5; 10)... Christ's once-for all offering of Himself is for all people for all time, and supersedes the Mosaic sacrificial system. Accordingly, the mystery of the eucharistic service, accomplished within the Divine Liturgy of the Church, is... a 'reasonable and bloodless sacrifice' to be understood as our sacrifice -offering to God... In the Divine Liturgy, instead of an animal or grain offering, we offer the Body and Blood of Christ to God. In a mystery known only to God, we thereby participate in the very Body and Blood of Christ offered once for all.32

The passage refers to how the Liturgy calls the Eucharist a “bloodless sacrifice,” which was also the name for the Temple’s grain sacrifices. The exact nature of the Eucharist however is considered a “Holy Mystery” and is not something exactly explained.

The Mysterious nature of the Eucharist makes it more difficult to judge the exact relationship of the Eucharist to the Old Testament prohibition on blood foods, which Dr. Rabbi Richard Rubenstein, Former President of the University of Bridgeport, sees as a key question regarding “Supersessionism.” Writing in The New English Review, he comments: “One of the most important aspects of the Dietary Laws was the strict taboo on the consumption of the blood of an animal, yet in the Eucharist it is Christ’s blood that is offered to the believer as ‘the medicine of immortality.’”33 Dr. Rubenstein writes that John 6:53-58, wherein Christ says “Whoever eats my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life,” has “been criticized as supersessionist… but [it expresses] the foundational conviction of Christianity that salvation… comes only through Jesus Christ.”34 He then draws a comparison to Judaism:

[F]or those early fathers of the Church who explicitly take up the comparison, Isaac's Akedah is an aborted Golgotha. They depict Jesus as the perfect Isaac and Isaac as lacking the capacity to redeem humanity because he did not really die on his wooden pyre. I should like to suggest that Christianity brings to manifest expression much that remains latent in Judaism… the difference was spelled out long ago in the following observation: What is latet (latent) in Judaism is patet (patent or manifest) in Christianity.35 [In] sacrificial religion… we find both the most important elements of continuity and discontinuity between the two traditions…36

The Church does not in fact abolish the Old Testament prohibition on blood foods, however. In Acts 15 we read how the early Church banned consumption of blood foods for Christians, as did Canon 67 of the Quinisext council.37By considering the Eucharist a Holy Mystery, Orthodoxy differs from Catholicism, which clearly considers a physical change (“Transubstantiation”) to occur in the Eucharist and would more likely see Christ’s instructions on the Eucharist as taking precedence over the prohibition. However, it also differs from traditional Protestantism, which emphasizes that the change is a spiritual one with the Divine Presence (“Consubstantiation”) and seems more compatible with a prohibition whose plain context was physical food. Regardless of whether there is a contradiction however, by transforming “sacrificial religion,” the Eucharist can be said to supersede previous sacrifices.

Fr. Anatoliy Bandura of Saint Nektarios Greek Orthodox Church discussed how Lactantius, an early Christian writer, described Christ’s Priesthood. Fr. Bandura explains that

Christ… received the dignity of everlasting Priesthood from the Father. In his vision, the Prophet Zechariah mentions the name of the everlasting Priest: ‘And the Lord God showed me Jesus (Hebr. Joshua)38 the great Priest standing before the face of the Angel of the Lord...’ (Zech 3:1-8) Paul calls Jesus the High Priest who supersedes the high priest in the Jerusalem temple (Heb. 3:1-2; 7:21). The high priest in the Old Testament is also a type of Christ, as is the case here.39

This idea of something important in the Old Testament prefiguring something in the New Testament is also reflected in the essay "The Law and the King," by Kevin Edgecomb, of Holy Cross Greek Orthodox School of Theology. Edgecomb writes:

As has been traditionally understood, Pentecost was the day on which the Law was given at Mount Sinai. In the Church, Pentecost is known for the descent of the Holy Spirit onto the earliest Christians, as described in the Book of Acts. In the hymnography of the Eastern Church, this dual import of the day is not lost: the latter is seen as superior to the former meaning.40

Edgecomb cites the Canon in Ode Eight from the Matins of Pentecost Sunday, which describes the Fiery Bush on Sinai speaking to Moses, zeal for God protecting the three singing Youths from the fiery furnace, and the Holy Spirit resounding on the apostles in the form of fiery tongues. The hymn concludes:

Ye that ascend not that untouchable mountain,

nor fear the awesome fire,

Let us stand on Mount Sion, in the city of the

living God,

And now form one choir with the Spirit-bearing

disciples.41

Note that the ancient Israelites did not ascend Mount Sinai, nor did the youths fear the fire, so the hymn addresses them with praise. Yet at the same time it calls those Israelites “us”! Edgecomb comments: “This is the ancient Christian perspective that the latter Pentecost fulfills, completes and enhances and supersedes the earlier, in that the people now have the Law written in their hearts through the direct action of God though the Holy Spirit.”42

Similarly, Robert Arakaki in The Biblical Basis for Icons uses “supersession” to reflect the higher place of Christ:

The opening lines of the book of Hebrews tell how the history of God’s progressive revelation reaches its definitive climax in Christ. [citing Heb 1:1-2] The superiority of Christ is proven by the fact that the coming of the Son supersedes all previous Old Testament revelations… the Apostle John makes a similar point: “For the law was given through Moses: grace and truth was given through Jesus Christ. No one has ever seen God, but God the One and Only, who is at the Father’s side, has made him known. (John 1:17-18)” The revelatory significance of the Incarnation lies in the fact where the prophetic message consisted of people hearing the word of the Lord, the Incarnation consisted of the Word of God coming to us in the flesh.43

In other words, Christ “supersedes” previous revelations with which they heard the Word, because He was the Word Himself. This is like an architect who builds a house: once he builds the house he/she intended, the task is accomplished and the house supersedes the blueprint. Yet the blueprint retains value for the new owner nonetheless.

Finally, when directly presented with the question, at this point in the scholarly debate, they accept it more often than deny it. Participants in two out of four significant discussions on the topic on Orthodox internet forums generally saw Orthodoxy as Supersessionist, while those on one forum tended to oppose the term.44 Peter the Aleut, the moderator on the leading “Orthodox Christianity Forum” commented: “Supersessionist Theology (pejoratively known as Replacement Theology) is not something foreign to our Tradition. In fact, the theology is based on the biblical doctrine of the Apostle Paul (Rom 9:1-11:36), not to mention the Prophets whom St. Paul quotes effusively and even some words of Christ Himself.”45

Tails: How Orthodoxy is not “Supersessionist”

Despite the descriptions above of the New Testament superseding the Old Testament or its elements, some Orthodox writers, focusing on the continuity between Christianity and Judaism, deny that supersession occurs or do not identify with the title Supersessionism. Herman Blaydoe explains:

We certainly can say that Christ's sacrifice has superseded the Temple sacrifice. There are aspects and explanations where the term "supersession' may indeed be appropriate, but that does not in any way mean that Orthodoxy supports the theological and modern concept of supersessionism en toto... [W]ithin an Orthodox theology, "supersessionism" is not helpful at all, it brings with it simply too much baggage. I am not sure that trying to rehabilitate it and bend it into an Orthodox context is a good idea.

Supersessionism carries with it the idea that the Church has replaced Israel, and that the Jews have been replaced by the Gentiles. This is simply not true. The Church is the continuation of Israel. We call it the New Israel, not because it no longer includes the Jewish people, but because it now includes ALL people. It goes beyond what it was; it does not replace what was before.46

In other words, the problem for Blaydoe is not that supersession occurs in some way, but that he, like Alex, sees Supersessionism as replacing one community (Israel) with another separate, noncontinuous one (the Church), or as one ethnic group replacing another.

Professor Gregory Benevitch of the St. Petersburg Institute of Religion and Philosophy on the other hand even disagrees with use of the word “supersede.” He writes that after the Holocaust, a theological movement developed in western Christianity that:

does not understand the mystery of the Church when it says that the Orthodox Church teaches that Christianity (i.e. the New Israel) claims to replace the Old Israel... The Orthodox Church does not claim to replace the Old Israel precisely because the New Israel (i.e. the Church) is nothing else but that very Israel of Abraham, Moses and the prophets, but already opened (revealed) to those non-Jews who believe in Christ.

The Catholic position could be clarified with a help of the "Commentary on the Documents of Vatican II"… Take for example [its statement]: "…the New Covenant confirmed, renewed and transcended the Old, and… the New Testament fulfilled and superseded the Old, but nevertheless did not render it invalid"( see v. III, p.18)… Here we find all this set of ideas, connected with such words as "supersede", "transcend" and "two covenants", which makes this Latin teaching ambiguous and unacceptable to Orthodoxy…

As for the Orthodox position, it is expressed best of all in St. Maximus' words about so-called Old Testament: "The grace is completely free of old age"(1.Th.Ec. 89). Which means that after Christ the Law and prophets, being given by Grace are still new. They were neither superseded by so-called New Testament, nor become "old", but, being at one with the Gospel, were revealed anew, as being given by the same Grace.47

Thus, Benevitch sees formal Catholic use of the word “supersede” as “unacceptable” to Orthodox thinking, because he sees the Church and New Testament as being a continuation of Israel and the Old Testament. He believes that the word obscures the real relationship between them, making the teaching ambiguous.

Another Orthodox commentor writes that the leading Orthodox theologian Fr. Thomas Hopko “has said that there is no such thing as a ‘New Israel’ in the supersessionist sense. There is, he said, a New Jerusalem, which is a concept that is present in ancient Jewish texts before the coming of Christ.”48 It is not clear whether Fr. Hopko himself used the word “Supersessionist”, but his statements suggest that in a way there is a “New Israel,” while in another way there is not. Fr. Hopko has said variously:

- God then sends his only-begotten Son… to be the New Israel, or the real Israel, to show what Israel is.49

- Israel was the firstfruit of the Old Covenant, now the new Israel50

- [I]n the Old Covenant, the qahal [congregation] was the qahal Israel. It was the assembly of Israel. In the New Testament, it’s the church of Jesus the Messiah. And in the New Testament it’s still the qahal Israel. How many times St. Paul speaks about that: we the Gentiles are grafted onto Israel. There is no new Israel; there is the one Israel of God, which is the people that God has gathered.51

- According to the New Testament Scriptures and particularly according to Saint Paul, the Church is in complete continuity with Israel, to the point that with all the emphasis in the New Testament on newness… we don’t see the expression, ‘new Israel.’ Therefore, when Saint Paul says, ‘upon the Israel of God’ (Galatians 6:16), he is speaking of the Church. Because of this emphasis, Orthodox Christians believe that the Church is historic Israel as it continues...52

One may think of “Supersessionism” in the sense of one group (the Church) replacing a completely separate group (Israel), and naturally conclude that Fr. Hopko is rejecting Supersessionism by seeing them as the same, continuous organization. Yet if Supersessionism simply means the Church superseding ancient Israel in any sense, then Fr. Hopko’s explanations do not exclude that this occurs. So long as some change exists, the New Israel may supersede its predecessor in the sense of being a later stage of it.

One may note the importance of the phrase “New Israel”, signifying a kind of “Israel” in the Christian era. A complementary term, the “Old Testament Church”, may provide perspective. As Fr. Hopko mentioned, Israel’s “Qahal” was its congregation, in Greek “Ecclesia,” typically rendered into English as “Church.” Thus, ancient Israel’s righteous congregation under its Covenant is sometimes called the “Old Testament Church” in Orthodoxy. The righteous Israelites’ expectation of Christ through prophecy is another reason they are considered part of the Church.53 Thus, when it calls itself a “New Israel” the Church means that this congregation is renewed and transformed with the Messiah’s coming.

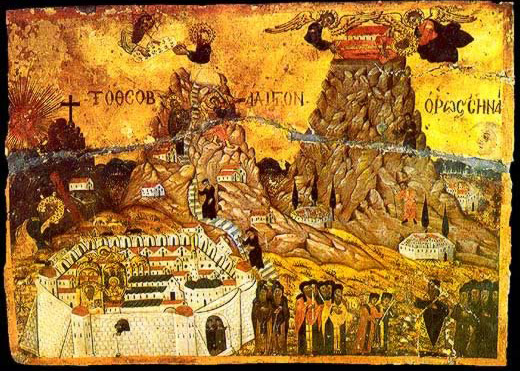

An icon that particularly reflects the continuity between the Old Testament and Christianity is the 17th century icon of St. Catherine’s monastery in the Sinai. The icon depicts not only Moses receiving the Law on top of the Mount, but also an image of angels carrying St. Catherine’s relics to it. The scene includes monks and the monastery’s chapels.

Further, while some critics of Supersessionism associate the theory with anti-Semitism, Orthodoxy does not think in racist genetic terms, like perceiving one racial group to be “the Church” “superseding” another, separate biological group (Abraham’s physical descendants) as if the latter cannot belong in the former. One proof of this is that Fr. Hopko says: “Jesus is a Jew, His Mother is a Jew, all the Apostles are Jews”54 Orthodoxy does not contemplate the possibility that a person could be spiritually superior to another due to his/her skin color or genetic makeup.55

Thus, keeping in mind the direct continuity Orthodoxy sees between itself and the ancient Jewish community, it makes sense that Orthodox writers object to the Church being seen as “superseding” Israel, when they perceive it as suggesting that the latter is necessarily disconnected, or that people are being separated based on race. Neither is the case.

Is anti-Semitism part of Supersessionism?

According to the journalist Robert Harris:

replacement theology… was a cornerstone of anti-Semitism within the Christian faith for a very long time… Replacement theology or supersessionism replaces mention of the Jews in the Bible, and the promises made to them by God, with that of Christians. Jews (as an analogue of the Israeli nation) become pariahs, rejects of history as having rejected the Son of God.56

Harris is correct to oppose anti-Semitism, however it is doubtful that Supersessionism is its cause, since a key passage its adherents use is Romans 9-11, which warns against boasting against the “branches” that had been broken off from the “olive tree” by the rejection. Paul’s logic is that if those branches lacked faith, non-Jewish Christians could lose it too, and the hardships of separation apply regardless of one’s background.

A common line of thought is that if Christians instead embraced a “Dual Covenant” theology leaving the Old Covenant unimpeded, then the anti-Semitism allegedly caused by Supersessionism would go away. This however is not the case, since the controversy caused by a lack of accepting Israel’s Kingly Messiah would remain. The apocalyptic expectations Dr. Idinopulos pointed to also suggest otherwise. The real issue for anti-Semitism therefore is not really the relationship between the covenants or even the Church and Israel, but of attitudes toward other religions.

Orthodoxy is not essentially hateful even toward non-Christians, because it has a more non-judgmental attitude towards individuals. Metropolitan Damaskinos of Switzerland writes that the truth of one's faith is lived 'not as a condition of being wrapped up in an arrogant syndrome of superiority with regard to other religions, but rather as a responsible service of dialogue and witness.’”57 The key here is a lack of arrogance towards others, not of course a belief that one’s beliefs are just as correct as another’s. Otherwise, we would not have anything to “dialogue” about!

Other writers repeat Metropolitan Damaskinos’ sense of humility and responsible witness. Deacon Stephen Methodius Hayes of the St. Nicolas of Japan missionary society comments: “We pray every day in Lent, ‘Grant me to see my own transgressions and not to judge my brother’. That is the spirit of true Orthodoxy. Nothing could be further from it than antisemitism.”58 Another feature of Orthodoxy, one which it shares with ancient Judaism, is a lack of the idea that guilt – like that of Original Sin or Christ’s Crucifixion – can be inherited biologically.59

Professor Benevitch takes on anti-Semitism in “The Jewish Question in the Orthodox Church.” He notes that beside himself, “There are many Jews among priests and monks as well as among the best theologians” in the Orthodox Church.60 Benevitch writes that the central obstacle to addressing questions of anti-Semitism in the way Protestant scholars have is that “Orthodoxy will never reject its own heritage… Orthodox Christianity is at least as faithful to its own Tradition as is Orthodox Judaism.”61 Yet one can address issues of guilt and enmity “quite simply - Everybody is guilty because everybody has sinned.’”62

He goes on to say that Jewish and Russian Christians share in the “universal character of the Church” and therefore must love eachother “in spite of all cultural, ethnic and other differences.” Benevitch explains:

[I]t is not correct to speak about the Church on the one hand and Israel on the other… the Christian Church is not a Church of the Gentiles… Christ's mission in this respect was to destroy the wall of separation between Israel and Gentiles. According to Apostle Paul, Christ… "is our peace who has made us both one and has broken down the dividing wall of enmity"(Eph 2.14).63

Benevitch explained that “This enmity on the part of the Gentiles was nothing else than what we now call anti-Semitism.”64 He added that Christ overcame it by bringing gentiles not into a newly created religion but into the “fulfillment of the Jewish faith” of the Patriarchs.65

While Benevitch focuses on unity inside the Church to overcome anti-Semitism, Metropolitan Kallistos Ware focuses on God’s relationship to Jews who are not part of the Church in his article “Has God Rejected His People?” He points out that Paul’s reaction to that separation “is not anger… but… ‘great sorrow.’”66 (Rom 9:2) Paul still looks “on them as his ‘kinsfolk’… and he says that he would rather be ‘accursed and cut off from Christ’ than saved without them.”67 Paul prays and expects that God will save “not just a ‘remnant’ among them but every one.”68 Ware adds:

They are still specially "beloved" by God (11: 29), "for the gifts and the call of God are irrevocable" (11:29). What is more, when the Jewish people eventually turn to Christ, this will prove an enrichment to the total Church which lies far beyond our present imagining. "If their failure means riches for the Gentiles, how much more will their full inclusion mean!" (11:12).

Ware concludes that this turning to Christ must be of their own free will and that we must never show them “the slightest disrespect or hatred.”69

These theologians’ writings are matched by statements by Orthodox leaders. The Ecumenical Patriarch declared 2013 a “Year of Global Solidarity.” In his Encyclical, he said that while “Peace has truly come to earth through reconciliation between God and people in the person of Jesus Christ,”70 he rued the state of conflict in the world: “Unfortunately… we human beings have not been reconciled, despite God’s sacred will. We retain a hateful disposition for one another. We discriminate against one another by means of fanaticism with regard to religious and political convictions.”71

Just this July, the Eighth Academic Consultation Between Judaism and Orthodoxy was held in Thessaloniki, Greece. There:

About 40 Christian Orthodox clergy, rabbis, and academics from around the world, including Russia, Georgia, Romania, Israel, France, Greece, Finland, and the United States met with local government and religious leaders….

Noting that Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew has declared 2013 the Year of Global Solidarity, Metropolitan Emmanuel said: “It is well documented that Greeks living in Thessaloniki at the time of the Shoah stood with their Jewish neighbors and friends. Today, more than ever, we must stand together to battle the evils of anti-Semitism, religious prejudice and all forms of discrimination.”72

Particularly notable are Sts. Alexander Schmorell, Maria Skobtsova, Fr. Dimitri Klepinin, Yuri Skobtsov, Ilya Fondaminsky (himself Jewish), and other saints who died resisting the Nazi genocide, because saints are for emulation. St. Alexander was a founder of the anti-Nazi group the White Rose, and was executed by the Nazis in 1943. A primes motivator for the White Rose was its Christian faith. Its leaflets were spread around Germany and Austria, and its second leaflet declared: “We wish to cite the fact that, since the conquest of Poland, 300,000 Jews have been murdered in that country in a bestial manner. Here we see the most terrible crime committed against the dignity of man.”73 Jim Forest, director of the Orthodox Peace Fellowship, writes why Schmorell proposed the name “White Rose” based on a story by the Orthodox writer Fyodor Dostoyevsky:

In one chapter of The Brothers Karamazov, “The Grand Inquisitor”, Christ comes back to earth, “softly, unobserved, and yet, strange to say, every one recognized Him.” He is suddenly present among the many people crowding Seville’s cathedral square, the pavement of which is still warm from the burning of a hundred heretics the day before. At this moment it happens that an open coffin containing the body of a young girl is being carried across the square on its way to the cemetery. They pass Jesus. “The procession halts, the coffin is laid on the steps at [Christ’s] feet. He looks with compassion, and His lips softly pronounce the words, ‘Maiden, arise!’ and she arises. The little girl sits up in the coffin and looks round, smiling with wide-open wondering eyes, holding a bunch of white roses they had put in her hand.” This merciful action completed, the Grand Inquisitor, having witnessed the miracle, orders Christ’s arrest. He is outraged at the boundless freedom Christ has given humanity.74

Conclusion: Orthodoxy as a Supersessionism that rejects anti-Semitism

The place of Orthodox Christians in Israeli society is an important topic. It is just a fact of life that many Israelis do not know Christians personally as might have been the case before,75 and must rely on third-person discussions or scholarship to reach an opinion. Something similar can be said about Americans’ own contact with Orthodox Christians.

While western scholars have the right intention of addressing cultural anti-Semitism and improving interfaith relations, there is the inadvertent risk of portraying the beliefs of Israeli and Palestinian Christians as anti-Semitic. For Orthodox Christians who focus on maintaining their core theology, this approach impedes the societal reconciliation that is desired.

Meanwhile, “Supersessionism” serves as the center in many of these discussions, and descriptions of it are also in flux. Descriptions of “Supersessionism” are usually negative and sometimes absolutist, calling into question whether they accurately describe traditional Christian beliefs. The common denominator in its various definitions is the idea that the New Testament or Church “supersedes” the Old Testament or Israel. The word “supersede” has meanings ranging from one thing having a higher authority or precedence, to overruling or replacing another thing. In practice the latter can be replaced completely or partly, or could be even fully incorporated into that which is new. Before placing a label on Orthodoxy, one must seriously consider the possibility that the topic itself is outside of Orthodox debate – Supersessionism is a word practically unused by Orthodox and even the word “supersede” is rare. Additionally, Orthodox thinking does not generally work in a legalistic way, yet the term “supersede” comes from legal reasoning.

To understand Orthodoxy, one must harmonize its theologians’ views. In general, Orthodox writings use the word supersede primarily in regard to Christ’s precedence over the Old Testament, while discussions of the Church’s relationship to Israel primarily focus on continuation. They describe: Christ superseding the law by transforming it, Christ’s sacrifice and the Eucharist superseding previous sacrifices under the Mosaic system of sacrifice, the Christian Pentecost superseding the Pentecost of the giving of the Law on Sinai by enhancing it. They see God providing a progressive revelation climaxing in Christ and Christ superseding the previous revelations in that way.

There are ways supersession does not occur. Gentiles do not “replace” Jews. Professor Benevitch rejects the idea that the Church “replaces” Israel because he sees them as a continuation. He goes as far as to say the Old Testament is one with the Gospel and revealed anew, and concludes that this means supersession does not occur between them. Most likely Benevitch rejects use of the word “supersede” because he perceives it in an absolute way. After all, a renewed, more detailed version of an agreement between two parties might be said to “supersede” the same agreement in its earlier state. Consequently, although Orthodox more often identify with “Supersessionism” than reject it, they remain divided due to these objections.

In any case, the Church's teachings do not support anti-Semitism. Differences between Jews and non-Jews are overcome by unity within the church, and God’s promises have not been revoked even to Jews outside the Church, based on their common roots. The real cause of anti-Semitism is not one’s position on the Covenants, but intolerance toward individuals of different backgrounds, which Orthodox teaching opposes. The Church's rejection of anti-Semitism is reflected in Church declarations and martyrs who resisted the Holocaust.

Let us return to the story of the boy and his uncle: Does the boy move the pond’s water? Yes, he does by stirring it, even though he has not moved the water from the pond. He is undeniably a “mover” of water, even though there are ways in which he does not move the water.

Orthodox Christianity must be “Supersessionist” in the most open sense of the word, because it gives Christ and the New Covenant a “higher place” than previous stages of religious development. Consequently, basic Christianity must also be “Supersessionist”: it cannot deny that it has brought something to move the waters of faith.