Was the addition of Filioque to the Nicene Creed necessary to combat Arianism in the West? This is an assertion often made in its defense, but is this really true?

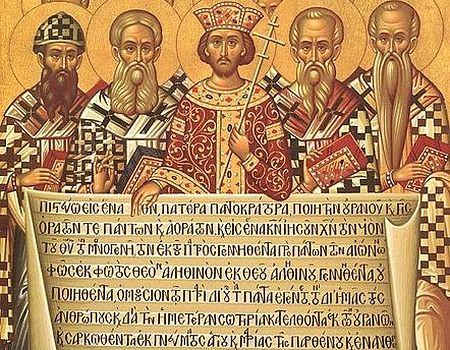

Filioque—”and the Son” in Latin—is a phrase later added to the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed in Western churches. This Creed or Symbol of Faith has been recited by Christian faithful as part of their liturgical and private devotional life since at least the fourth century, and is universally considered to be the litmus test of Christian orthodoxy. It was arranged in A.D. 325 at the First Council of Nicaea, later to be made complete at the First Council of Constantinople some 56 years later.

When a clause on the Holy Spirit was appended to the original creed, it contained the following (in part):

Καὶ εἰς τὸ Πνεῦμα τὸ Ἅγιον, τὸ κύριον, τὸ ζῳοποιόν, τὸ ἐκ τοῦ Πατρὸς ἐκπορευόμενον, τὸ σὺν Πατρὶ καὶ Υἱῷ συμπροσκυνούμενον καὶ συνδοξαζόμενον . . .

And in the Holy Spirit, the Lord, the Creator of life, Who proceeds from the Father, Who together with the Father and the Son is worshipped and glorified . . .

In 1014, the Latin-speaking church in old Rome began to recite the Creed with the Filioque included, changing the second line to: “who proceeds from the Father and the Son.” This action resulted in the removal of the Pope from the diptychs in Constantinople, and an eventual, heated encounter between Cardinal Humbert and the Ecumenical Patriarch in 1054. I realize that unfamiliarity with this issue can lead one to deem it a splitting of hairs, but it really isn’t. What we believe about God influences everything else about us, and especially as the Church.

But laying most of those discussions aside for now, let’s examine if this addition to the Creed really helped in the orthodox struggle against Arianism.

Arius was a presbyter from Alexandria (ca. A.D. 256–336), a disciple of the martyr St. Lucian of Antioch (240–312). The theology of his namesake (which later took on other forms) can be summarized as a belief that Jesus was a creature. In other words, using the phraseology of the Arians in the fourth century, “there was a time when [Jesus] was not.”

In response to this heresy, the Church clarified at Nicaea:

And whosoever shall say that there was a time when the Son of God was not (ἤν ποτε ὅτε οὐκ ἠν), or that before he was begotten he was not, or that he was made of things that were not, or that he is of a different substance or essence [from the Father], or that he is a creature, or subject to change or conversion—all that so say, the Catholic and Apostolic Church anathematizes them.

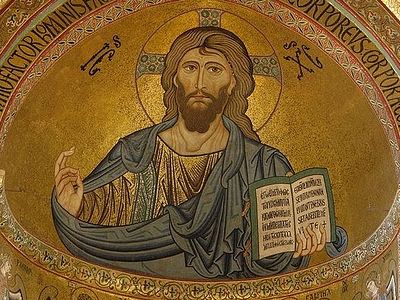

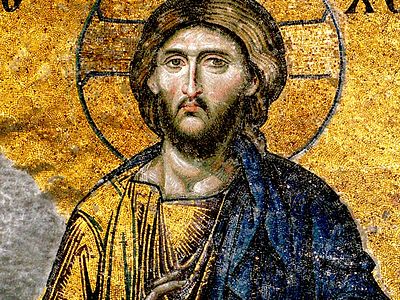

Arianism teaches that Jesus is not “of one essence with the Father,” or homoousios(the word used by St. Athanasius of Alexandria), but is rather a creature who came into existence when Jesus was born of the Virgin Mary. Orthodox Christians reject this, confessing that Jesus is eternally begotten of the Father, of one essence with the Father, and the eternal Logos of God who became incarnate as theanthropos—God-Man.

Apologists for the Filioque today will claim that it was necessary for the Spanish Christians of the sixth century, as they struggled to emerge from Arian dominance in Western Europe. The third anathema of the Synod of Toledo (Spain) in 589 is leveled against anyone who:

… does not believe that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son, and is coeternal with and like unto the Father and the Son.

As an overreaction to Arianism, Spanish Christians attempted to compensate by making the Son to be a joint Cause (αιτια) or Origin (αρχε) of the Holy Spirit in eternity. At least, as best as we can tell. There are very few records of this synod or even how this phrase was actually understood. It’s possible they only meant what in Greek is called προειναι by “proceeds,” since the Latin procédit could refer to either ἐκπορεύεται or προείναι. But the original Creed in Greek is an exact quotation of John 15:26: παρὰ τοῦ πατρὸς ἐκπορεύεται (“who proceeds from the Father”).

Even if we could know what the Synod of Toledo meant, we know that Christians did not include this phrase in the Creed until at least the 11th century, and this only in the Roman and Frankish churches (the latter of which may have begun using it by the ninth century—even laughably claiming that the Greeks had removed it from the Creed!). If one interprets the Second Ecumenical Council strictly, there is no possibility of changing the Creed as it is used liturgically—at least not as a unilateral decision by any one, local church. This is not to say that the Creed is the final word on all intricacies of theological discourse, but it does lay down certain boundaries for conciliar belief.

Further, making the Father and the Son to be a joint Cause or Origin of the Spirit does not actually help avoid the errors of Arianism. One might even argue that this “flattening” of the Father and the Son has led to a whole host of subsequent errors and heresies in the West. Instead of elevating the Son to be coeternal with the Father, Latin theology has demoted the Spirit to be someone less than the Father and the Son, while also disrupting the monarchia of the Father.

Ironically, the purpose of the final clause of 381 was to elevate the Spirit in the creedal terminology, and not to elevate the Son (as the original Creed had already dealt with that issue):

Not until the 360s did it become clear that the Nicene party would succeed in their defence of the decision of 325. By then fresh disputes were raging over the status of the Holy Spirit, whom extreme Arians were treating as a created being, subordinate to both Father and Son. It was the three Cappadocian fathers, Basil the Great, his brother Gregory of Nyssa, and Gregory of Nazianzus, whose trinitarian teaching was approved at the Council of Constantinople in 381, clearly defining orthodox Christian belief. —Hugh Wybrew, The Orthodox Liturgy, p. 28

The Filioque is then a sort of reversion back to the errors of the extremist Arians near the end of the fourth century—the errors refuted by the clause on the Holy Spirit added to the Creed in 381—where the Spirit is subordinated to the Father and the Son. Again, the Church already believed that the shorter creed of 325 was sufficient to protect the dignity and co-eternality of the Son with the Father, not to mention the ways in which the prayers and liturgies of the Church upheld the orthodox doctrine.

As a result of flattening the Trinity and subordinating the Spirit, God for many in the West today is a generalized deity: the capital “G” of Freemasonry and the “God we trust” of American currency and the pledge of allegiance. Rather than identifying the Source of the Trinity with the person of the Father, the West has come to refer more to a God-in-general than the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit; a flattening of the essence at the expense of the persons.

A proper balance is maintained in the Greek fathers between the oneness of the Holy Trinity and the three, unique persons—and this balance derives from a focus on the Father as the sole Cause, Source, and Origin of the Trinity. Contrary to revisionist, Filioque apologetics, the unity of God is not preserved by flattening the Trinity at the level of essence or ousia (or worse, at the level of person or hypostasis):

[T]he divine ousia or essence was not to be understood—as with other generic terms—as what it is to be divine; that would not have safeguarded the unity of God, just as one human nature does not mean that there is only one man. Rather the divine ousia was understood to be the Father’s being—the being of the one God we call Father—which has been extended in unbroken continuity to the Son, through begetting, and to the Holy Spirit, through procession. —Andrew Louth, Introducing Eastern Orthodox Theology, p. 28

The continual struggle against Arianism in the West following the fourth century was thankfully not as necessary in the East. Hugh Wybrew notes that the liturgical language of the Greek-speaking churches made Arianism impossible to openly maintain:

These trinitarian disputes left their permanent mark on Eastern worship, particularly in the doxologies with which liturgical prayers concluded. The early Christian tradition had been to pray to the Father, through the Son, and in the Holy Spirit. But this tradition had been cited by the Arians in support of their teaching that the Son was subordinate to the Father. ‘Glory be to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit, now and for ever and to the ages of ages’ became the characteristic ending of Byzantine liturgical prayers, even when, as in the case of the Lord’s Prayer, it was not appropriate. For the God to whom the Church continued to pray corporately in the Liturgy was God the Father, as the eucharistic prayer and other older prayers made clear. —The Orthodox Liturgy, p. 28

As later Christological heresies arose—dealt with by the third-through-seventh ecumenical councils—there was never once an insistence on anything remotely resembling the Filioque, nor was that issue in particular ever anything more than a footnote of doctrinal history. Each council in succession began with a short mention of the heresies of Arius, Nestorius, and others, and then quickly moved on to address the concerns of their own day. When the Franks begin to use the Filioque as a rhetorical tool against the Greeks in the ninth century, St. Photius the Great reminds them at the Eighth Ecumenical Council (A.D. 879–880) and in hisMystagogy of the Holy Spirit that the Father is the sole Cause (μόνος αίτιος ο Πατήρ) of both the Son and the Spirit. In so doing, he was only repeating the statements of the Cappadocian fathers of the fourth century—the same fathers who helped codify the Creed against the Arian errors to begin with.

Between the strong words of the Symbol of Faith, and the exclamations of the Greek liturgical texts and devotional prayers, a proper balance between the oneness of God and the Trinity of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit was maintained. Eastern prayers always both begin and conclude with statements on the co-eternality of the persons of the Trinity, as well as their eternal existence as one God (with the Father as Source and Origin).

This over-emphasis removed any need for additional phrases in the Creed, especially those which could be seen as an open invitation for a relapse into the more extreme forms of Arianism at the end of the fourth century—the very forms of Arianism the Creed of 381 was intended to defeat.