Ankawa, Iraq, June 22, 2014

About 120 parishioners attended Sunday mass at St. Elias Chaldean Catholic Church in Ankawa where Father Shahar gave a homily about the need for reconciliation in Iraq. PHOTO: MATTHEW FISHER/POSTMEDIA NEWS

About 120 parishioners attended Sunday mass at St. Elias Chaldean Catholic Church in Ankawa where Father Shahar gave a homily about the need for reconciliation in Iraq. PHOTO: MATTHEW FISHER/POSTMEDIA NEWS

Convert to Islam or face the sword.

That was the stark message Christians in the Syrian city of Raqqa received last year when ultra-fundamentalist Sunni extremists, proclaiming themselves to be members of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), seized power and launched a reign of terror against Shiites and Christians that has included beheadings and at least three crucifixions.

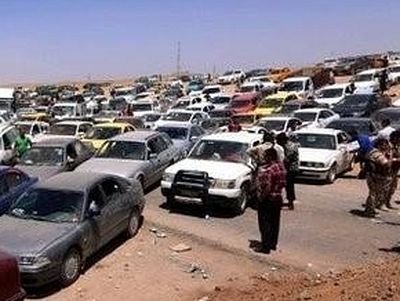

Aware of ISIL’s ferocious reputation for murder and mayhem, thousands of Christians who lived in Mosul and the surrounding Nineveh Plain fled in panic when ISIL rebels captured Iraq’s second largest city from government forces on June 10. Many of those who escaped have sought refuge in this Christian enclave in the Kurdish city of Irbil, only an hour’s drive away from Mosul.

“All who are left there now are a few handicapped or sickly Christians,” said a Chaldean Catholic nun wearing a blue habit whose religious community fled Mosul on foot, walking north for four hours on June 10 along with thousands of other Christian and Muslim refugees.

They all feared persecution at the hands of the insurgents who had suddenly arrived in their midst because they follow a harsh 7th century interpretation of the Qur’an that demands not only that women mostly stay indoors, but that church bells must never be rung, crosses must never be displayed and Christians must pay a “gold tax” in return for their lives.

Iraqis attend Mass at the Chaldean Church of the Virgin Mary of the Harvest, in Alqosh, set in the seventh century Saint Hormoz monastery built into a hill overlooking Alqosh, a village of some 6,000 inhabitants about 50 kilometers (31 miles) north of Mosul, northern Iraq. (AP Photo)

Iraqis attend Mass at the Chaldean Church of the Virgin Mary of the Harvest, in Alqosh, set in the seventh century Saint Hormoz monastery built into a hill overlooking Alqosh, a village of some 6,000 inhabitants about 50 kilometers (31 miles) north of Mosul, northern Iraq. (AP Photo)

The nun pleaded repeatedly that her name and her order not be disclosed, lest the rebels read her comments on the Internet.

“They’ve taken down every monument in Mosul, whether they depict Iraqi political figures or Catholics,” she said in impeccable French that she polished during a year studying in Montreal.

“They removed a statue of the Virgin Mary but as far as I know they have not destroyed it.”

About 120 parishioners attended Sunday mass at St. Elias Chaldean Catholic Church in Ankawa where Father Shahar gave a homily about the need for reconciliation. “I hope that peace will come again to Syria, to Baghdad, to Mosul and to Iraq,” was the priest’s only reference to the sectarian violence now convulsing the country.

Fear permeated the congregation on a day when ISIL fighters claimed another border town with Syria, making it easier for them to move arms in both direction because they control a large swath of northern Syria where they have been fighting Bashar Assad’s regime.

Iraqi children pose for a picture at a camp for displaced Iraqis who fled from Mosul and other towns, in Khazer area outside Irbil, northern Iraq, Sunday, June 22. Sunni militants on Sunday captured two border crossings, one along the frontier with Jordan and the other with Syria, security and military officials said. (Hussein Malla/The Associated Press)

Iraqi children pose for a picture at a camp for displaced Iraqis who fled from Mosul and other towns, in Khazer area outside Irbil, northern Iraq, Sunday, June 22. Sunni militants on Sunday captured two border crossings, one along the frontier with Jordan and the other with Syria, security and military officials said. (Hussein Malla/The Associated Press)

There have been Christians in Iraq since the 1st century when two disciples of Jesus brought the gospel here. As recently as 2003 Iraq had 1.5 million Christians. But since then there have been more than 70 attacks on churches, several priests have been murdered and the number of Christians has plummeted to less than less than 500,000. This latest spasm of sectarian violence is likely to lead to another mass exodus.

A 72-year-old parishioner, who would only give his name as Dominique, said he had been forced to leave Mosul for Baghdad in 1960 after his father was murdered for being a Christian. When the church he attended in Baghdad was blown up a three years ago, he, his wife and their son sought sanctuary in Irbil’s Christian suburb of Ankawa.

“To be a Christian in Iraq is to be subjected to terrorist acts,” said Dominique, who many years ago received a graduate degree in engineering from Wayne State University in Detroit. Dominique’s distant cousin, Archbishop Paulos Faraj Rahho, was kidnapped from his car and murdered in Mosul six years ago.

“We move from city to city in Iraq because we have believed in the promises of the government and of Muslim clerics that we would be safe,” he said, adding with grim laugh, “we now believe that we have run out of places to hide.”

An Iraqi child works on a temporary mosaic of Pope Francis’ face made from the area’s produce, including wheat, beans and lentils to commemorate an upcoming harvest feast, at the Chaldean Church of the Virgin Mary of the Harvest, in Alqosh, a village of some 6,000 inhabitants about 50 kilometers (31 miles) north of Mosul, northern Iraq. (AP Photo)

An Iraqi child works on a temporary mosaic of Pope Francis’ face made from the area’s produce, including wheat, beans and lentils to commemorate an upcoming harvest feast, at the Chaldean Church of the Virgin Mary of the Harvest, in Alqosh, a village of some 6,000 inhabitants about 50 kilometers (31 miles) north of Mosul, northern Iraq. (AP Photo)

Dominique’s son, Michael, who attended mass with his parents, said that although his family was safe for the moment in Iraq’s Kurdish autonomous region, “we cannot forget that Mosul collapsed in only two hours.

“We believe that the Peshmerga (the Kurdish army) are strong and on paper the Kurds give us more rights than anywhere else,” said Michael, who has a master’s degree in computer science from a British university. “Still, we have this feeling that we are guests in our own country. We know that the common issue that binds Sunnis and Shiites is that they are Muslims.”

While acknowledging that they had little information about Canada’s reaction to the plight of Christians in Iraq and Syria, Christians, Dominique and Michael said the perception among Iraq’s Christians was that the Canadian government was more interested in maintaining cordial relations with Muslim countries than in helping Christians in mortal peril. Nor did they feel that there was much chance that they would be allowed to settle in Britain or the U.S.

Friar Gabriel Tooma enters the Chaldean Church of the Virgin Mary of the Harvest, set in the seventh century Saint Hormoz monastery built into a hill overlooking Alqosh, a village of some 6,000 inhabitants about 50 kilometers (31 miles) north of Mosul, northern Iraq. (AP Photo)

Friar Gabriel Tooma enters the Chaldean Church of the Virgin Mary of the Harvest, set in the seventh century Saint Hormoz monastery built into a hill overlooking Alqosh, a village of some 6,000 inhabitants about 50 kilometers (31 miles) north of Mosul, northern Iraq. (AP Photo)

“We see that they give passports to Muslim terrorists and accept homosexuals who say they have been discriminated against and yet they refuse us entry,” Michael said.

The nun, Michael and his father all said in separate conversations that with Catholic, Orthodox Christian and Coptic communities also under siege in Syria and Egypt the only likely future for Christians was to leave the Middle East.

“We are in no danger right now but who knows in this country,” the nun said. “We have no idea what they will do next. The Kurdish area is the quietest place in Iraq, but until when nobody knows.”