A delegation from the Eastern American Diocese of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia recently carried out a pilgrimage to Moscow and its environs. One of its members—Eastern American Media Office Director Reader Peter Lukianov—agreed to share his impressions.

—Peter, you were born into a family of first-wave Russian émigrés. Please tell us about your family. How did they wind up in the United States?

—That is correct—I represent the third generation of the Russian emigration. My parents are Archpriest Serge and Matushka Lubov Lukianov. My father currently serves in the Eastern American Diocese, at the St. Alexander Nevsky Diocesan Cathedral in Howell, New Jersey.

My grandfather’s parents were from Kazan. In the terrible years of the Revolution, they fled Russia and, ultimately, wound up in Shanghai. That was where my grandfather, Protopresbyter Valery Lukianov, was born. In Shanghai, his family became acquainted with Bishop John of Shanghai. It was the same Holy Hierarch John who ordained my grandfather a priest.

My great-grandparents—Archpriest Peter and Matushka Raisa Mocharsky—lived in Volhynia prior to their arrival in the United States. My great-grandfather was a fourth-generation priest. When he arrived in New York in the 1950s, he brought a portable iconostasis with him in order to more quickly organize a parish and begin serving the multitude of Orthodox émigrés.

The majority of my mother’s forebears were from the city of Ekaterinoslav (today Dnepropetrovsk), and were only able to emigrate to the United States by the mercy of God. My grandfather Ilarion Ivanovich and grandmother Polina Ivanovna Afanasenko met in a Nazi labor camp. At the end of the day, they were saved by one American soldier, who took a liking to my grandfather and hired him as a cook. Grandfather told us about how the Americans would ask him to cook them Russian borscht, because it was the best food they were getting. The Americans transported my grandparents from Germany to America; that is how they were able to avoid deportation to the USSR, where imminent death awaited them.

My father and mother were born in New York, and I was born in New Jersey. And even though I am an American citizen, I consider myself Russian.

—Do you plan to continue in the footsteps of your grandfather and father and serve the Church?

—It would be too bold of me to say that I want to become a priest, though my parents certainly hope so. Everything is in God’s hands.

—Is this your first time in Moscow?

—No, this is my third trip.

—Did they tell you about Russia in America?

They told us a great deal about Russia, about Moscow, and from childhood we were taught that if we do not preserve our Orthodox Faith and our culture, then they will be lost. That is how our loved ones raised us, placing all hope for preserving and passing on the Russian Orthodox spirit to our generation. After all, they believed that the true Russia had disappeared, gone into the past, never to return. No one expected that the Soviet Union would collapse and that a spiritual revival of the Russian people would begin.

—What were your first impressions visiting Moscow? What do you remember above all?

—The churches, of course. We as Americans are not accustomed to a church on every street, or to a collection of so many holy relics or wonderworking icons in a single place. In the diaspora, we have the Kursk Root Icon of the Mother of God, and several other icons that are venerated as wonderworking, but here you have one in virtually every church! Our pilgrimage group attended the divine services in Holy Resurrection Church at Ascension Gorge. As I entered this church, I experienced something indescribable: so many holy icons all around, so many generations of people had prayed before them, asking for the forgiveness of their sins, for the salvation of Russia, for the protection of the Patriarchal throne of Moscow! It was difficult to take it all in at once. The divine grace that one feels when he visits the churches of Moscow made a particular impression on me.

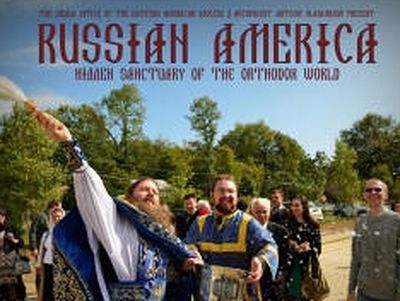

—How many people came in your group pilgrimage group this time?

—In addition to myself, there are also two members of the Eastern American Diocesan Media Office. Our group is headed by Hieromonk Alexander (Frizzell), the dean of Holy Cross Monastery in the state of West Virginia, the fastest growing Orthodox monastery in America. It is a marvelous place: all of the divine services are performed in English. There are close to thirty monks at the monastery, of which only one was born Russian and two were raised Orthodox; the rest are all natural-born Americans who converted to Orthodoxy on their own. They have no Russian roots, but they love Russia! On July 17, the feast day of the Holy Royal Martyrs, they hung an Imperial flag on the monastery building with a banner that read, “God, save the Tsar.” Often the monks receive the names of Russian saints in tonsure: Venerable Seraphim of Sarov and Alexander of Svir… Just recently, one monk was tonsured and named for Hieromartyr Hilarion (Troitsky), Bishop of Verey. For those who live at this [Sretensky] monastery, Russian saints are relatives and loved ones.

There are fifteen Orthodox jurisdictions in America—Greek, Antiochian, Serbian, Romanian, and so on, but there aren’t many English-language monasteries, which is why many Americans come to Holy Cross. This is a genuine Russian island—everything there is as it is in a Russian church, only in English, and they even sing Znamenny chant![1] Father Artemy Vladimirov said of this place, “It is an American monastery with a Russian soul.”

One young man from our group is visiting Russia for the first time. All his life he had been a parishioner of the Orthodox Church in America and, having come to Moscow and become acquainted with church life here, he was shaken to the core. He would walk everywhere with eyes opened wide in wonder, trying to make sense of all that he was seeing and experiencing. Father Alexander comes to Moscow once a year, and each time brings two monks from the monastery, so that they can see with their own eyes the heart of Orthodox Russia.

—What monasteries has your group visited in Moscow?

—We were in Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra, in Sretensky Monastery, Sts. Martha & Mary Convent, we prayed in Danilov and Donskoy Monasteries, visited Khotkovo and Alexeevsky Convent in Krasnoe Selo—the latter is where we are staying; with the blessing of Abbess Xenia, our dear friend Archpriest Artemy Vladimirov is hosting us there. The hospitality we have been shown in Krasnoe Selo is so remarkable, and wonderfully reflects the kind and lovingly generous nature of the Russian soul!

—The Russia your parents and teachers nostalgically told you about in your childhood significantly differs from the Russia of today. Having received an opportunity to compare the two, did you get the impression that something important, something deeper, has been lost?

—It is impossible to lose—how can you lose grace? Even if the churches and monasteries are surrounded by skyscrapers, this externality has no effect on the internal, the spiritual. Certainly, all around is a contemporary metropolis, loud and sometimes dirty streets, and endless streams of cars. But once a person steps through the doors of the church, he enters another world entirely.

When I read about Sretensky Monastery, looked at pictures of it, I was certain that it was located somewhere outside the city, in the forests and meadows. The first time I came to Moscow, I was stunned to see that the monastery is located in the very center of the capital, densely surrounded by residential buildings. This was in 2004, when a ROCOR delegation visited Russia for the first time, led by our First Hierarch, Metropolitan Laurus—this was before the unification of the Russian Orthodox Church and the Church Abroad. I was not a member of the official delegation; rather, my father, brother, and I coincidentally decided to visit Russia on pilgrimage at the same time. We entered Sretensky Monastery and did not quite know how to act—we were brought up being told that there was a “Red Church” in the USSR, and so viewed everything with a degree of skepticism.

We entered the church. It was the feast of the Lord’s Ascension, and the service was taking place. Suddenly the choir literally thundered, “Thou hast ascended in glory, O Christ our God…” I had goose bumps, and unexpectedly began to cry like a baby. I am standing in church, tears flowing, and I cannot comprehend where I am. It is impossible to relate this in words. Three minutes ago, I was walking along dirty and busy streets of a bustling modern city, and suddenly I am in paradise! So the grace has certainly not been lost.

—What would you like to wish Orthodox Muscovites?

—The third First Hierarch of the Russian Church Abroad was Metropolitan Philaret (Voznesensky). His remains were found incorrupt, and we very much hope that, as time passes, he will be glorified. His final words before he reposed—he typed them out on his typewriter—were “Hold fast to what you have.” It bothers me when I hear that many Russian people to not appreciate what they have. Imagine if you did not have the relics of Venerable Sergius of Radonezh; if instead of 800 churches in Moscow, there were only five; if instead of thousands of wonderworking icons, only two. What would you do? How would you live? I love Russians with all of my heart, but it seems to me that the people who live here have grown accustomed to the sacred. We in the diaspora have similarly grown accustomed to the Kursk Root Icon. It is located in the cathedral not an hour and a half ride from my house. When it is taken to the parishes, 150 people will gather to pray, though it could be many more. People have grown accustomed to the sacred, to its constant nearby presence, but I think this is unacceptable.

This is a time when people around the world, even Americans, are looking to Russia, because she is the last bulwark of Orthodoxy. If we do not appreciate this, do not preserve it, it will be the end of everything. The last time I visited Russia, I had an interview with the now-reposed artist Pavel Ryzhenko. He said this: “Russia, Holy Rus’, is the last front. The Orthodox in America are the reserve force. There will come a time when you, too, will have to decide—you are either Americans, or you are Orthodox.” That is why now, more than ever before, we must hold fast what to we have.