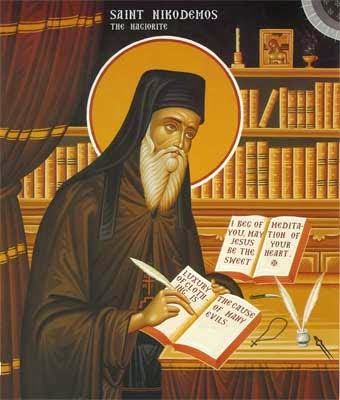

The repose of our father among the Saints Nikodemos the Hagiorite is commemorated on July 14/27. St. Nikodemos was an ascetic and hesychast and a prolific author of the depths of the spiritual life. He is credited with compiling the works that make up the Philokalia as well as the canons of the Church, adding to them an interpretation of each canon. St. Nikodemos is also known as a father of the “Kollyvades” movement which emphasized the importance of frequent reception of Holy Communion and the distinctness of Sundays in the liturgical life of the Church. More on the life of St. Nikodemos can be read here.

In the summer of 2013, Archimandrite Nikodemos Skrettas, a professor of pastoral theology in the School of Theology of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, who has researched and written extensively on the work of St. Nikodemos and the Kollyvades Fathers, offered a lecture to a group of American seminarians gathered in the Greek village of Petrokerasa, outside Thessaloniki. His words reveal a great love of the Fathers, and in particular the fathers of the Kollyvades “movement,” and in turn demonstrate the great love of the Fathers possessed by the Kollyvades Fathers themselves:

* * *

Brothers in Christ, I hope that you will look to me and see and hear me as a brother, who will impart to you the words of an illiterate, as St. Symeon the New Theologian said. When St. Symeon was relating his deepest theology, he would say “these are the words of an illiterate.” Why? Because, according to the Saint, light is knowledge, and not knowledge light. He wanted to stand against the rationalism of the West which thought man was enlightened by many doctorates, and acquiring much knowledge of things. In the Orthodox Tradition we live and experience exactly the opposite: when we commune at the Divine Liturgy then we chant “we have seen the true light.” St. Isaac the Syrian says there exists faith from knowledge and knowledge from faith. In other words from hearing one believes—he hears the preaching of the Gospel and he’s convinced. When however he agrees and believes then comes the next knowledge—of God. This knowledge is charismatic—like that spoken of by St. Symeon. It is in this context that the Kollyvades Fathers lived and theologized.

The Kollyvades Fathers

The Kollyvades Fathers

The Turkish yoke was very a difficult period for the Orthodox East due both to the dangers and challenges facing the nation and the social changes that were happening, and to the decisive and deadening ritualism that crept into Divine worship. Therefore the social and spiritual life of the Greek was a search for a balance of the old and that which was coming—Tradition and renewal and regeneration. At the very same time the race was “losing blood” because of those leaving and going to Europe, from the proselytism of western missionaries, the very harsh Islamization from the Turkish yoke, and from the tactic of Turks to gather children and make them into Turks and take them away. Within this context there developed an anti-western spirit—not a hateful one, but in staunch defense of the Orthodox faith.

Within the personalities of the saints, the nation and the people began to develop a protection for themselves. After Patriarch Gennadios Scholarios the Church began to take on the role of ethnarch—the leader of the nation. The different Orthodox peoples—the Greeks and others—began to gather into local communities to retain their culture and faith and the diaspora began to develop. The learned of the nation attempted to maintain and build themselves. The holy martyrs laid the foundation by their own blood. Teachers were trying to teach again that which they had forgotten or lost. There was a deep, deep search for spiritual identity in this period of the Turkish Yoke, and they were trying to turn back to the living Tradition of romiosini.

St. Kosmas of Aetolia is a great example. In the darkness of the Turkish period he founded over 200 schools, trying to gather and inspire all the Orthodox people to rise up, and also the holy Kollyvades Fathers who were trying to bring to life again the experience of the Divine Liturgy. Against them were Greeks who had gone to the west and returned, such as Adamntios Korais, and were trying to bring back bizarre pagan worship and values, within the context of rationalism and the French Revolution and people who were trying to expound encyclopedic knowledge such as Voltaire. This atheist enlightenment from the west had an idea of metakenosis—that the Greeks had given the light to west and the now west was required to give the light back to the east.

In response the Kollyvades tried to give back to the people the Orthodox light. They insisted on and promoted the Tradition of the Church, and thus their movement was known as philokalic—denoting a love of the beautiful and a new hesychastic movement. Thus, against the lights of the western enlightenment they took the light which is the experience of the Divine Liturgy—the worship of the Church. Against those who were simply highly educated they placed those people who become gods by grace through worship. The same struggle exists today but now we have their examples and personalities to look to. There is decline on one side due to ritualism and the focus on externals, and undiscerning modernization on the other side which totally perverts Orthodox Tradition. The Kollyvades Fathers were trying to keep this balance and to do so in enlightened way. They struggled to wake the people up with the ethos and way of life of the Saints, and the strength of experienced worship. They struggled to teach the Christians both the dogma and ethos of Church. Due to this they left at times the small world of Athos and entered the larger Orthodox world and they were spiritually renewing the Church. St. Athanasius of Paros in particular intensely struggled with the enlightenment figure Korais—not because the Saint was fanatically anti-western but because he was struggling against a perversion of Orthodoxy.

Archimandrite Nikodemos Strettas

Archimandrite Nikodemos Strettas

In the western tradition man is always asking for more and more light—in other words for more and more knowledge. And through the Kollyvades Orthodoxy is not restricted to the boundaries of Orthodox Greece, but they belong to the whole Church—they represent the universality of Orthodoxy, and this is important because thus we are saved from the ethno-phyletism of some. There are local Orthodox churches but there is no such thing as ethnic churches—this is a delusion and heresy in the eyes of Orthodoxy. Therefore the tradition of the Kollyvades must not be left in museums, but it gives life to the Church both now and in future. The Kollyvades were the most learned of their age—their works could take up a whole library. They simplified texts, interpreted ancient texts, and edited and prepared huge texts with a critical and scientific approach. It is enough to look at the Pedalion[1] and Manual On the Five Senses of St. Nikodemos to see thiss. At end of this handbook of spiritual counsel he explains, develops and dissects the makeup of the human heart. He goes into physical anatomy in order to teach how prayer happens in the heart.

Their presence on Mt. Athos was a blessing of God for the Church. They returned to the depth and core of the Patristic Tradition of the Church. They are Saints and learned teachers who understood very well the Tradition and show us the Orthodox way. But more than anything they were learned and experienced in Divine worship of the Church and on this point they were uncompromising, and particularly when they spoke of the Eucharist, but also when talking about the importance and privileges of Sunday. Thus with wisdom and discernment they fought against the legalism of their age as pertains to worship. Where was this found? First of all it is found in the very rare reception of Holy Communion. Even on Mt. Athos monks who were entirely dedicated to God sometimes communed only three times a year. Canons exist which say that if forty days have not passed you cannot commune again. In the typikon of the monastery of Philotheou from the nineteenth century, and thank God Elder Ephraim changed this, it is written that no one can commune more than once every forty days, even if they are on their deathbed! The Kollyvades Fathers said this is insanity! The Kollyvades said this cannot be the life of the Church.

This misunderstanding comes from the Byzantine Period. Emperor Leo VI the Wise in 920 AD married for the fourth time, but the Church gave him a penance for this. There was a room in Agia Sophia where the emperor changed his clothes, and he was penanced to stay in this room throughout the Liturgy. As there ensued a huge struggle between the emperor and Patriarch on this issue there was convened the so-called Council of Unity in 920 which restored relations between the Patriarch and emperor, and a canon was written stating that all those married for a third time were penanced for five years with no Communion, and after the fifth year they could commune only three times a year, on Pascha, Nativity, and Dormition. During the Turkish period this canon became a part of the liturgical books, such as the Horologion, but the last part about a third marriage was cut off, and so they thought it was for all Christians. The Kollyvades said this is impossible and were very strict in their reaction to this. St. Nikodemos discovered this and it’s in the Pedalion.

St. Makarios of Corinth

St. Makarios of Corinth

Within the writings of the holy Fathers, within the commentaries on the Liturgy by Saints such as St. Dionysius the Areopagite, St. Germaons, St. Symeon, St. Nicholas Cabasilas, etc, and also in the monastic tradition was found that which the liturgical books and Typikon and canons called for. They returned to all these sources. From the roots up they renewed the Tradition of the Church. They brought the power of liturgical tradition which was totally without delusion and without perversion back to its rightful place.

The Kollyvades dealt with two main controversies: the question of the Eucharist and how often one may participate in Holy Communion, and the second was the place of Sunday in the liturgical life of the Church, and the controversy around the serving of memorial services on Sunday. In the liturgical Tradition of the Church we don’t have Soul Sundays, but rather Soul Saturdays, which is the day for the martyrs and the reposed. Sunday is the day of the Resurrection of the Lord. Every week is the recycling of the Lord’s Pascha. The Sunday after Pascha is the Sunday of Consecration, starting again the cycle of Sunday Liturgies.

St. Gregory the Theologian has a text on the new Sunday in which he talks very much about the importance of Sunday, which is the first and most important feast of the Church as we see in the Revelation of St. John the Theologian. This day has a special place in the liturgical life of the Church and the Kollyvades continued very strongly this tradition. Sunday is a day of Resurrection, joy, etc. On Sundays three things not allowed: kneeling, fasting, and memorial services (although funerals can be served) as these are all connected with mourning. If the fortieth day of someone’s repose falls on a Sunday it should be memorialized on Monday rather than Saturday and we know this from the fact that from Lazarus Saturday until Thomas Sunday no memorials are celebrated—all are moved to a later date.

In the Skete of St. Anne’s in 1754 the main church was destroyed. A man named Demetrios gave a considerable amount of money for the rebuilding and he asked in return that they celebrate the memorial services for his dearly reposed. The Fathers themselves began the process of rebuilding. Of course, memorials should be held on Saturdays, but on Saturday there was a general market in the Athonite “city” Karyes and it was essential that they take their handiwork there in order to live. So when could they do the memorial services? They decided to do them on Sunday, and this was the beginning of the controversy. The Kollyvades Fathers who knew well the worship of Church could not agree to memorials being done on Sundays. The problem isn’t kollyva[2] or memorials but rather that they would be trampling on the day of Resurrection. They truly understood what Sunday meant—the day of recreation. Even if this could happen in the world for some reason, it should never happen on Athos with people who know the Typikon.

There was such controversy over this that some of the Kollyvades Fathers were even killed—they found their bodies in the sea—they were drowned. This is especially true of the group that had connections in the Patriarchate. The Kollyvades Fathers did not defend themselves but the other side was continually sending people to have them condemned. They struggled even unto martyrdom.

Many lies were told about them, and their enemies called them “Kollyvades,” but the term stuck. They were also called Masons because they were a small group that didn’t commune much with others and seemed mysterious to others. Some people said they put Communion in their skufos[3] for later or that they didn’t believe Holy Communion was Divine which is absolutely ridiculous, and many other wholly undeserved and ridiculous things. They were not believed in their day and age and it was not until the twentieth century arrived that people began doing special studies of them and discovering their texts, and they become well-known, and that is where this ironic word “kollyvades” (a person who makes kollyva) comes from, and it became a banner or flag of their group. The Kollyvades Fathers are a great source of inspiration for all Orthodox faithful. They present to us the sources of the Orthodox faith and this is precisely why they are a source of inspiration. They sought not the light of earthly knowledge, but rather the light of Divine knowledge through the worship of the Church. Their lives bear witness that they received this light, and were illumined to pass on to the rest of the Church, even though it cost them dearly in their own lifetimes. May their martyric example continue to guide the Church in this day and into the future.